In the early, halcyon days of nuclear power, British prowess in engineering enjoyed some of its finest hours. Here was a clean power and an unlimited resource that the country had the capability to make a reality.

Even before the award-winning television series Edge of Darkness, Chernobyl and Fukushima, the control rods had slipped down to quench the ardour of a nuclear future. It turned out that the free lunch offered by fission came with the high costs of security, waste management and decommissioning.

Could there now be a new dawn? This was a question explored today by the House of Lords Science and Technology Select Committee.

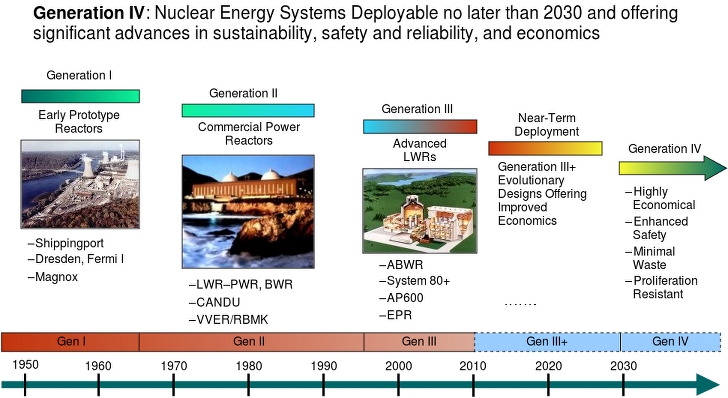

Two emerging technologies give enthusiasts reason to believe once again. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) see a future in which the gargantuan power plants of the past are replaced by distributed smaller reactors that are much more flexible and efficient. New Generation IV technology (see graphic) has the potential to transform nuclear power into the clean and highly efficient energy source first envisaged.

Credit: Enoshd – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

When asked what is needed for the United Kingdom to reclaim its role in a nuclear future, Professor Mike Tynan, chief executive of the Nuclear Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre in Rotherham appealed for an industry strategy for the UK that looked forward 50-100 years. Fundamentally, the UK needs to decide if it wants to be a service industry in the nuclear sector or have ownership of the new technology, he said.

Dr Michael Bluck, director of the Centre for Nuclear Engineering at Imperial College London cautioned that in 2040, a novel Generation IV reactor will not look like it does today and recommended the interim step of starting with SMRs built using existing Light-Water Reactor (LWR) technology.

For David Orr, senior vice president Nuclear at Rolls-Royce, the future should be even more constrained. A single preferred approach to future reactor design should be selected in advance and resources channelled so that the winning formula has scale to get off the ground with an energy cost that could become competitive.

In itself, the UK energy market is too small for a viable domestic nuclear industry. However, the deployment of 15-20 conventional SMR units would be sufficient to offset the research and development costs and give UK industry, in particular high-value manufacturing supply chains, a position to compete for international business.

The international competition is expected to be strong. France and China should be able to build upon their existing capabilities. Meanwhile, Professor Grace Burke, Director of the Materials Performance Centre at Manchester University told the committee that in the United States the Department of Energy is already funding 20 advanced reactor design prototypes.

The Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is currently preparing a roadmap to chart a future for the development of nuclear power in the UK. Originally expected in autumn 2016, it has still to appear.

US technology company NuScale Power is not waiting for a roadmap. They already have their SMRs on the drawing board and are seeking advanced manufacturing partners to collaborate on reactor construction projects. Mr Tom Mundy, their Managing Director, UK & Europe, told the committee that their first plant in the US is expected to be generating power in 2026. The same could be achieved in the UK.

For the Generation IV reactor designs the uncertainties increase further. There is much fundamental research still to do. New materials need to be created and design feasibility confirmed. It will be expensive. One solution is international collaboration to share knowledge, risk and cost.

Here again Brexit casts a shadow, as it demands the exit of the UK from the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), which has become an integral part of the EU’s construction of a market for nuclear power across Europe. Professor Burke says she was “disheartened” by this development, which would have a negative impact on research with the loss of collaborative links upon which this research depends.

Throughout the Science and Technology Select Committee hearing the tone was subdued, appearing more like a memorial ceremony for the bygone days when hope for a new nuclear future was enticing.

Perhaps unexplored was a shared awareness that the prevailing political climate is not conducive to the laying down of huge bets on technologies that, at best, may not pay off for several decades.

So, there is some time before the dawn and we have yet to see upon which country the sun will rise.

By John Egan

Follow on twitter: @johnmegan