Globalisation has been blamed for many of the woes of the lower middle classes in western societies, as well as the subsequent rise of populism in the west, Donald Trump’s candidacy and the vote for Brexit.

But this deeply held belief has been challenged by a Resolution Foundation study which found that, contrary to popular belief, lower middle incomes in the developed world have, in fact, not stagnated.

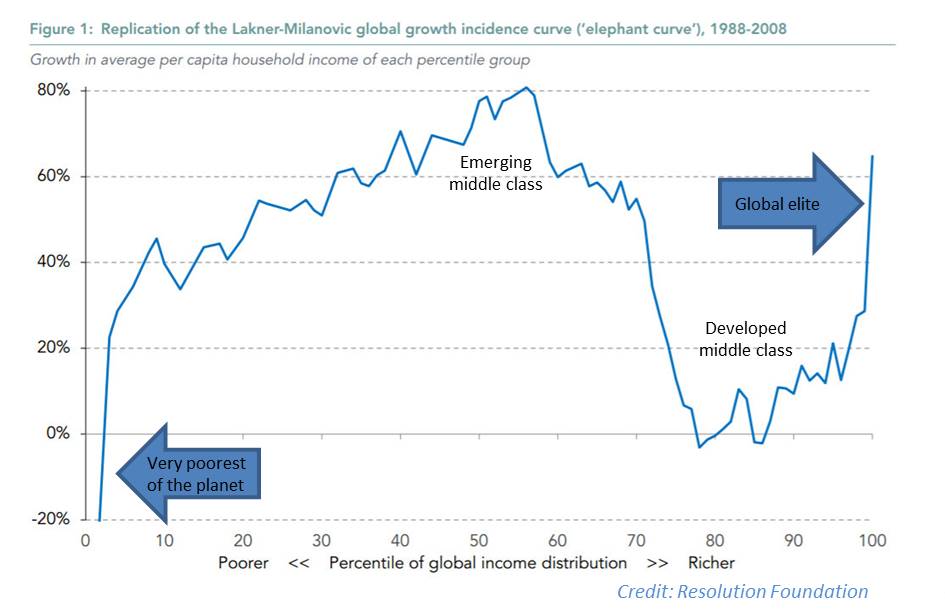

The Resolution Foundation, a British think-tank, revisited a highly influential graphic – the “elephant chart” – produced by Branko Milanovic, a former senior official at the World Bank, and found that it could be reinterpreted.

Mr Milanovic’s “chart that explains the world” showed how globalisation, over the past 30 years, was responsible for the stagnating incomes of the middle classes in developed countries, while the global super-rich became even richer, and China saw its middle class booming.

First published in a 2012 World Bank working paper, the chart purports to represent the income gains made by the world’s population between the period of ‘high globalisation’ in 1988 (the fall of the Berlin wall) to the start of the global financial crisis in 2008 (the fall of Lehman Brothers).

It looks like an elephant raising its trunk with the tail on the left representing the poorest in the world (locked out of growth) and the trunk on the right the richest (the booming global elite).

Middle classes in China and other emerging economies (in the middle of the distribution) and the planet’s economic elite at the end of the chart (forming the raised trunk of the elephant) seem to have hugely benefited from the effects of globalisation.

Meanwhile, “the biggest losers (other than the very poorest 5 per cent), or at least the ‘non-winners’, of globalisation were those between the 75th and 90th percentiles of the global income distribution whose real income gains were essentially nil,” according to Mr Milanovic.

These “non-winners” include ordinary people in the west, mainly in the US (and supposedly Donald Trump’s core supporters) and Europe, pointing to a decline of the developed world’s middle class, which would partly explain the rise of populism in rich countries.

However, in its report the Resolution Foundation noted two main flaws in the way the original data used to produce the “elephant chart” were aggregated:

- A higher number of countries was used in later samples

- Differences in population growth were not taken into account (making it difficult to compare the incomes of the lower middle classes over time)

Based on this diagnostic, Adam Corlett, an analyst at the Resolution Foundation, produced new charts correcting these apparent distortions.

Mr Corlett told Chief-Exec.com on Tuesday that “one thing that emerges from the data is just how astounding income growth has been in China. Between 1988 and 2008 typical incomes tripled (200 per cent growth – rising to >500 per cent for the richest) – even faster than many have interpreted from the hump of the original elephant chart. Incomes in most other developing countries, conversely, have grown less phenomenally, with growth rates that are not too different from the mature economies.”

This new adjusted version shows that the low and middle incomes and so-called “non-winners” have not fared as badly as first thought. It actually shows that their incomes have even improved over the years.

The president of the Resolution Foundation, Torsten Bell notes in his blog that after correcting the population growth bias “we find that incomes of the working/middle class of the developed world rose by around 25 per cent rather than stagnating”.

“And once we exclude [Japan and the ex-Soviet satellites states] from the analysis the income growth towards the top of the distribution rises again to around 50 per cent over the period, or around 2 per cent a year, a long way from stagnation.”

Globalisation did not harm the low and middle classes of the rich world.

Nevertheless, globalisation still throws up a range of challenges that need to be addressed but these are rooted in domestic issues, which need to be dealt with by governments and policy makers.

Mr Bell says governments should not “be let off the hook”.

“Domestic policy matters. To fetishise globalisation as the cause of all our ills is to let too many domestic policy makers off the hook for decisions they make, for problems they leave unaddressed and for the lower incomes working people experience as a result.”

According to the Resolution Foundation blaming the world’s woes on globalisation is not good enough. Governments and their policies should also be held accountable.

By Katia Yezli