Today sees the publication of a comprehensive review of the state of the nation and the potential impacts of Brexit in the OECD’s 2017 economic survey of the UK, writes John Egan.

Like a bus that fails to arrive, the absence of a return to productivity growth since the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007 is a matter of popular discontent.

Productivity growth is the source of improved standards of living for a nation’s citizens and it is expected. For more than four decades until 2007, the UK economy saw its productivity grow like clockwork at about 2 per cent each year. Since then UK productivity has flat-lined.

To restore productivity growth the 2017 Economic Survey of the UK economy by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), released today, advises that “income and wealth, housing, and education and skills stand out as areas where progress is needed, and on which greater labour productivity would have had a beneficial impact”. Indeed, the report adds that resulting inequalities in these areas felt by less educated workers in more remote regions may have been behind the outcome of the Brexit referendum.

The solution recommended by the OECD in its 140-page report is distilled into a three-line epigram:-

- Securing higher living standards requires a revival in labour productivity

- Reducing regional discrepancies to support aggregate productivity growth

- Raising competencies of low-skilled workers to make the economy more productive and inclusive

The puzzle of this lacklustre productivity growth has been covered previously in Chief-Exec.com and the reasons for this remain poorly understood.

Last week the UK Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) described a productivity growth that “disappoints again”, and once again downgraded its expectations for productivity growth with a negative impact on the medium-term outlook for the public finances. Previous forecasts had assumed an eventual pick-up of productivity following “temporary, albeit persistent, influences” responsible for the post-crisis period of weakness. Ten years on we are still waiting.

FER17: as productivity growth disappoints again we review our forecast assumptions and the rationale underpinning them. pic.twitter.com/gPLo7NxX1l

— OBR (@OBR_UK) 10 October 2017

The full consequences of the OBR analysis will appear in November, but it is expected that this will wipe out a sizeable portion of the rainy-day fund that Chancellor Philip Hammond had set aside for Brexit-related contingencies.

Low productivity growth since the GFC is by no means solely a UK phenomenon, and has afflicted most developed economies. The UK, however, is among those most badly affected.

A sobering picture is painted of the chasm that must be crossed for education and skills in the UK to be able to provide the human capital for a modern, productive work force.

The OECD has sought to illuminate the issue with a highly detailed study of productivity of companies around the globe. In this, companies that sit at the technological frontier are seen to have had a healthy growth in productivity. On the other hand, it is the laggards in the race to be innovative with dismal productivity outcomes that weigh heavily on the performance of their economies. It is a matter of the diffusion of innovation down from the frontier firms to those following that appears to be obstructed.

So-called “zombie companies”[1] that remain in business despite being unprofitable, through easy access to cheap finance, effectively trap their employees and capital in an unproductive environment. The OECD estimates the percentage of capital and labour locked into zombie firms in the UK is about 18 per cent and 13 per cent respectively.

The OECD supports an industrial strategy that creates “the conditions where winners can organically emerge and grow, instead of trying to prop up failing industries or picking winners”.

Levels of capital investment in the UK have been systematically less than the average for G7 and OECD economies for several decades. A striking example of this is the low number of industrial robots in the UK. The UK Economic Survey urges targeting future investment where it will have most impact – the sectors and regions that have fallen behind and where “disparity in labour productivity remains large and persistent”.

Regional transport infrastructure, research and development, housing and skills are identified by the OECD as the levers to promote a broader growth of productivity and shared well-being.

A sobering picture then is painted of the chasm that must be crossed for education and skills in the UK to be able to provide the human capital for a modern, productive work force.

- Over 25 per cent of working aged adults in the UK have low basic skills in literacy and numeracy

- Low basic skills in the UK prevail across all education levels, and the percentage of young adults with low basic skills is higher than the average across the OECD

- Unlike most other countries, young adults in the UK do not have stronger basic skills than the generation approaching retirement

- Despite the large number of courses offered, the provision of post-secondary vocational education and training is much more limited than compared to most other OECD countries

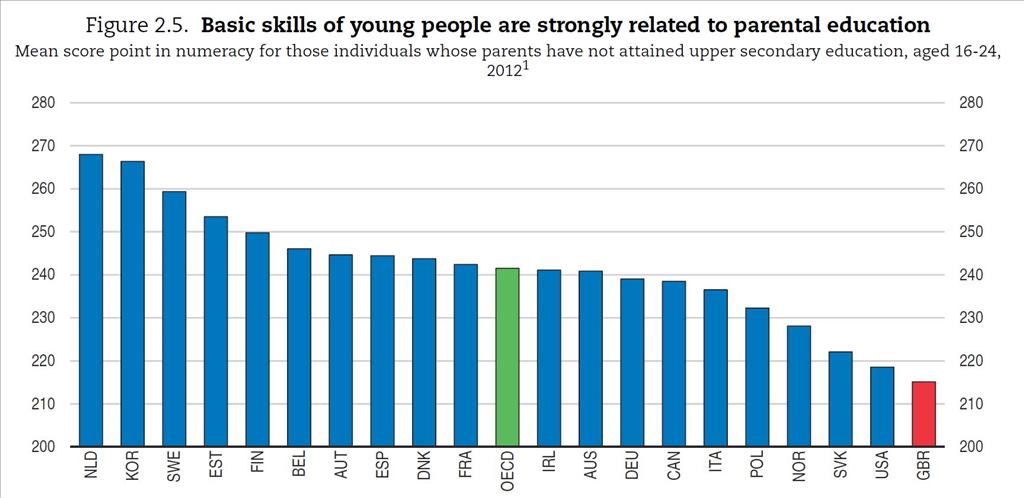

- Young people whose parents have low levels of educational attainment have the lowest level of basic skills proficiencies than in all other countries surveyed (see below)

- While almost all 16- and 17-year olds attended secondary education, participation in secondary and post-secondary education at age 18 at 60 per cent, is well below the OECD average

- Low-skilled workers in the UK have comparatively lower earnings than low-skilled workers in other G7 countries, and the effect of higher skills proficiency on wages is particularly important in the UK.

The OECD report does point to measures that promise some improvement of the above situation, but a reader is left with an awareness that there is still much to do.

On Brexit

Unsurprisingly, a disorderly Brexit is identified in the OECD report as a major medium-term risk to the UK economy in general. Failing to negotiate a satisfactory trading relationship to replace EU membership is expected to push the sterling exchange rate to new lows and lead to sovereign rating downgrades. “Business investment would seize up, and heightened price pressures would choke off private consumption. The current account deficit could be harder to finance, although its size would likely be reduced,” the report said.

The specific challenge to revive the growth of labour productivity in the UK economy is also compounded by Brexit, through a possible “diminished trade openness, but also owing to a weaker research and development intensity and a smaller pool of skills”.

The report concludes that, “immigration has enhanced [UK] living standards through higher labour resource utilisation and productivity gains, which shows the critical importance of keeping the labour market open for foreign workers. EU migrants in the United Kingdom have a higher educational attainment than in most other EU countries and recent research has shown a positive impact on productivity related to the higher skills that migrants possess and the possible complementarity between their skills and those of the UK population”.

As lower immigration would reduce labour force and productivity growth the report recommends that “rapidly concluding negotiations to guarantee the rights of EU citizens is a priority to sustain labour supply and ensure further progress in living standards”.

In the paradoxical world of Brexit, it seems that the presence of immigrant labour, particularly from the EU, which has been considered so much a part of the problem, is also part of the solution recommended by OECD to retain and perhaps enhance UK living standards in its aftermath.

[1] Zombie companies are defined as those that are over 10 years old and with interest costs exceeding operating income for at least three consecutive years.

Headline Photo Credit: kentoh/Shutterstock.com