So it is agreed, capitalism is broken – for many. Can it be fixed to make it more “inclusive and sustainable”? Yes, says a politician and an economist, but their remedies diverge. It depends on who is to blame, writes John Egan.

Michael Gove, United Kingdom Environment Secretary (pictured left) a leading proponent of Brexit, gave a keynote speech to the Policy Exchange think-tank yesterday. It ventured well beyond his ministerial responsibilities to diagnose the maladies of capitalism in its current incarnation.

“Economic power has been concentrated in the hands of a few and crony capitalists have rigged the system in their favour and against the rest of us”, says Mr Gove, possibly with an eye on today’s headlines.

Because of this, the many losers from the capitalist world order are tempted by the panacea of populists – nationalism and protectionism – that will suppress the creativity and innovation upon which a prosperous future depends, Mr Gove went onto assert.

‘Economic power has been concentrated in the hands of a few and crony capitalists have rigged the system …’ Michael Gove, United Kingdom Environment Secretary

Then Mr Gove went on to finger who, in his analysis, is to blame.

“And since 2008, the outlook has grown darker for most. With productivity stalling, so unemployment has increased in many advanced economies, particularly among the young and those with fewer skills. Wage growth has stagnated and expectations of future security have eroded as occupational pension schemes have been plundered or dissipated in value.

“These unfortunate trends have gone hand-in-hand with an increased concentration of wealth, and power, in the hands of the already wealthy and powerful. It’s not just that members of the cognitive elite, the well-educated and well-connected, have the networks and mobility to insulate themselves from economic shocks, it’s also the case that deliberate policy decisions have rewarded those who’re already asset rich.

“Loose money policies, from the European Central Bank to the US Federal Reserve, have increased the prices of assets, from real estate to equities, strengthening the economic position of the already wealthy.”

So, it is the fat cats and the bankers who are mainly to blame.

In his lengthy oration Mr Gove drafted a landscape of where solutions may be found to make capitalism more inclusive and sustainable – and popular. His emphasis was on policies to support investments that drive up productivity and develop the UK’s human and natural capital resources.

A week earlier to the day, Álvaro Pereira (pictured right), acting chief economist at the OECD, took a similar tack whilst presenting the organisation’s 2018 Economic Outlook.

For Mr Pereira the clouds that remain from the Global Financial Crisis are being blown away by a global economic growth expected to reach almost 4 per cent in 2018. The monetary policies of low interest rates and quantitative easing have done their job. Now fiscal easing, reducing the constraints of austerity, “is the new game in town”.

However, risks remain in national indebtedness, rising oil prices, trade disputes and financial volatility. What is needed to make the global economy truly sustainable and more inclusive are structural reforms.

A bone of contention concerns the OECD “Going for Growth” recommendations and the apparent reluctance of national governments to implement its policies. Less and less has been done with each year since 2011.

One priority area for such structural reform is education and skills – or in the words of Mr Gove “human capital”.

‘Look at that sea of red! That sea of red is name and shame for the governments that they are not doing enough about education’ Álvaro Pereira, acting chief economist at the OECD

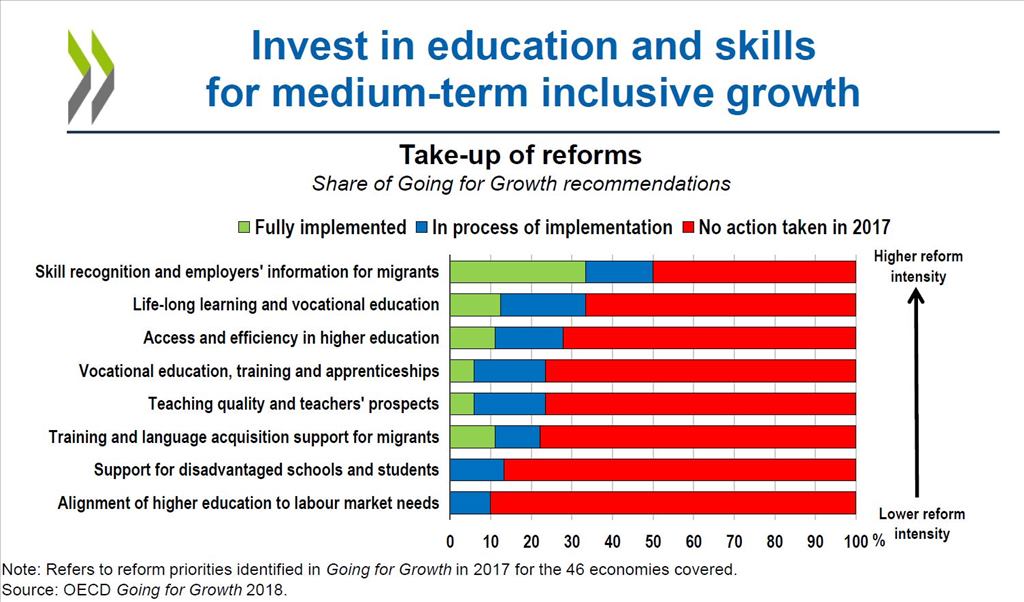

Mr Pereira revealed the lack of uptake of the Going for Growth recommendations in this area.

“We think that something has to be done about this. So we look at some of the areas that we think are crucial to going forward in terms of reforms. One of them in order to address the labour shortages, in order to make growth more inclusive, is to invest in education and skills.

“And what I would like to emphasise here, this graph shows you the take-up of reforms in several areas in terms of life-long learning, apprenticeships, skills recognition, vocational education and what this graph says – is that the green shows whether these reforms have been implemented by governments, and the red tells you the reforms have not been implemented or are at early stages of implementation.

“Look at that sea of red! That sea of red is name and shame for the governments that they are not doing enough about education. They are not doing enough about skills reform. More needs to be done in order to make skills the priority for the country.

“It is not enough to talk – you need to walk the walk. And for this we believe this is very important going forward and this should be top priority for the governments of the OECD and the rest of the world.”

Other recommendations concerning digital infrastructure, university-industry collaboration and reducing barriers to innovation also formed the required ingredients of structural reform for economic growth. All of this in conjunction with the reduction of trade barriers.

So, in the view of Mr Pereira, it is government policies for structural reform that are seriously lacking to move the global economy in the direction of sustainable and inclusive growth.

Michael Gove and Álvaro Pereira share a common goal – to save capitalism from the growing anti-capitalist sentiment that could eventually bring about its undoing. A politician who famously denounced experts during the Brexit campaign, and an expert who passionately urges politicians to recognise the road to inclusive economic growth.

In their different visions are fragments of a sustainable future. But economic and political realities resist their reconciliation.

Headline Photo Collage: Michael Gove (Credit: Policy Exchange)

and Álvaro Pereira at the OECD Forum 2018 (Credit: OECD)

Rights reserved under Creative Commons license