When it should be holding the beacon higher and brighter, the UK is abandoning its important role as a promoter and defender of the system which has kept the peace and created the prosperity that has characterised post-World War Two Europe, concludes Geoff Kitney.

It is highly unlikely that Nigel Farage deliberately chose to announce his decision to stand aside Brexit Party candidates to help the Conservatives win the British election just hours after the 30th anniversary of the most momentous event in modern European history – the fall of the Berlin Wall.

For Farage, Europe is only worth thinking about as a cause to be rid of. Doing whatever it takes to sever Britain’s ties to Europe is his only motivation, to the point of making as sure as he possibly can that British voters don’t get the chance to reconsider their narrow decision over three years ago to leave the European Union.

So, as Europeans reflected on the anniversary of November 9, 1989, and its consequences for Europe then, since and in future, Farage announced that he had instructed 300 Brexit Party candidates in Tory held seats to stand down to ensure that the pro-Brexit vote would not split and thus increase the risk that a Remain candidate would win.

Farage and his ilk might prefer to look away and say that they want no part of Europe, but events in Europe will always force their way into the affairs of Britain.

Three decades after an event which was the greatest blow for freedom since the defeat of the Nazis 45 years earlier – and victory for a future of Europe for which the UK paid with almost one million dead and injured soldiers and civilians – Farage showed that, as far as he was concerned, post-Berlin Wall Europe was a cause to which he believed Britain had nothing more to contribute.

Not for him any reflection on the bigger lessons of the years since the fall of the Wall, nor about the challenges that post-Wall fall events and changes now pose for Europe.

His perspective remains tightly and strictly limited to his “little England” mentality.

The staggering thing about this is that the lessons of the 20th century are that it is utterly impossible for “little England” to remove itself from the impacts and consequences of what happens in Europe.

Farage and his ilk might prefer to look away and say that they want no part of Europe, but events in Europe will always force their way into the affairs of Britain.

What Farage and co are doing will not stop this happening: If they get their way, as appears increasingly likely, all they will achieve is to reduce Britain’s ability to influence European affairs and the European events which will inevitably impact on the UK.

The surprising thing about this is that those who see Brexit as absolute folly, not just for the UK economy but for Britain’s long term and fundamental interests in the evolution of European affairs and the future of the European Union, seem to have failed to come up with a compelling narrative for their cause.

The Berlin Wall anniversary is surely an event which compels deep reflection on the state – not just of Germany – but all of Europe and what that means for the peoples and nations of Europe. Yet there seems to have been precious little of this in the UK, unsurprisingly not by the Brexit forces but, very surprisingly, not by the Remain forces.

Reading a lot of the commentary and analysis by European writers that has been provoked by the anniversary, the overall thrust has been that things have not turned out as had been expected at the time of the fall of the Wall.

The forces of freedom that the fall of the Wall were predicted to unleash – leading to what historian Francis Fukuyama predicted might be the End of History, with liberal democracy and market capitalism being the ultimate destination of humanity – have produced unpredicted results. Thirty years on, new walls have been erected both in reality and in the thinking of Europeans.

A number of writers have noted that Europe still has a great divide between west and east, which runs along the line where the Iron Curtain had once been.

The argument goes that the former Soviet bloc countries which were freed from Soviet tyranny with the collapse of the Soviet Union think fundamentally differently about their place in the world to those on the western side of the Iron Curtain whose lives had become freer and increasingly prosperous after the defeat of fascism in 1945.

Those on the western side, it has been suggested, resolved that the best way to guarantee that there would be no return to the aggressive nationalism which ultimately led to both the first and second world wars was for the post-war European democracies to pool their sovereignty in a way which made them economically, strategically and politically interdependent and therefore fundamentally constrained from going to war against each other.

This was the genesis of the European Union and today’s dominant European political order in which all those inside the EU have essentially a common destiny.

But, for those on the other side of the Iron Curtin, for whom the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Iron Curtain meant the end of the Communist system, of a dictatorial central authority in Moscow and a form of shared sovereignty which had imposed virtual enslavement of its people, the European project, its clamps on the autonomy of the individual members states, all directed from a Brussels-based central bureaucracy, had too many echoes of the tyranny they had just escaped.

The UK, as it edges its way towards the EU’s exit door, now has more in common with those former eastern bloc drifters than its Western European partners.

Those putting this analysis forward as an explanation for today’s growing European divide argue that this explains the appeal in former Soviet bloc countries – most apparent in Hungary and Poland, but also increasingly apparent in the former East Germany – of what is being called “illiberal democracy”.

“Illiberal democracy” is characterised by a desire for living in a clearly defined nation state in total control of its own sovereignty, including its national borders and bent on defending against outsiders or intruders (such as refugees) what are seen as essential cultural traits and traditions (even when it involves the restriction and curtailment of individual rights). The politicians who are tapping into this sentiment – right-wing populists – have been reaping big political rewards.

There is much that rings true about this analysis and helps explain the current drift in Europe towards the conservative, extreme right.

But what is extraordinary about this is that that drift is also occurring in the nation which has held the brightest beacon of freedom and democracy of all the western European nations – the United Kingdom.

The UK, as it edges its way towards the EU’s exit door, now has more in common with those former eastern bloc drifters than its Western European partners. When it should be holding the beacon higher and brighter, the UK is abandoning its important role as a promoter and defender of the system which has kept the peace and created the prosperity that has characterised post-World War Two Europe.

The Brexit forces – starting at the top with Prime Minister Boris Johnson – argue that the UK’s membership of the EU has circumscribed its ability to be more prosperous, freer and more in control of its own circumstances, including the ability to defend its own border and protect its cultural traditions. Johnson’s Brexiters – driven by the fear of Farage’s threat to the unity of the Conservative Party – see no compelling case for Britain to be a force inside the EU for the values and political system which lie at the heart of Europe’s post-war success.

With Britain possibly now having passed the point of no return – a certainty if the Conservatives win a clear parliamentary majority at the December election – the battle to prevent the slide towards a wider and more dangerous “illiberal Europe” will be harder to win. Brexiters should – but almost certainly won’t – be reflecting on this.

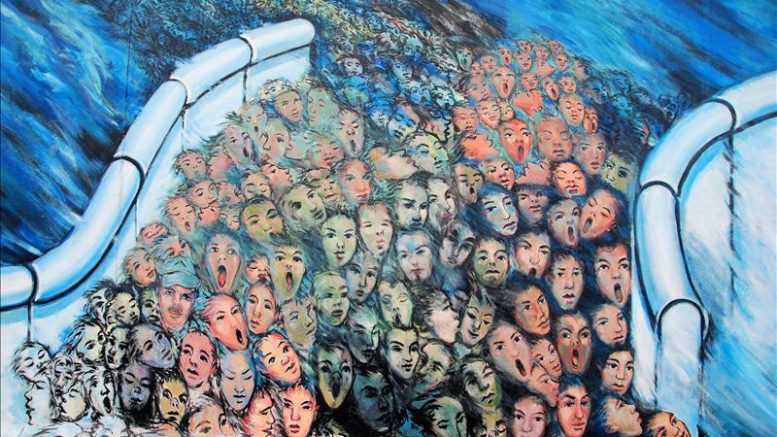

Headline image credit: meunierd/Shutterstock.com