In the forthcoming trade-off between migration controls and access to European Union (EU) markets, the UK economy could be hit from both sides, leading to a possible lose-lose outcome.

In the forthcoming trade-off between migration controls and access to European Union (EU) markets, the UK economy could be hit from both sides, leading to a possible lose-lose outcome.

This is the conclusion reached by The Economic Impact of Brexit-induced Reductions in Migration, a report published last Thursday by the National Institute of Social and Economic Research (NIESR).

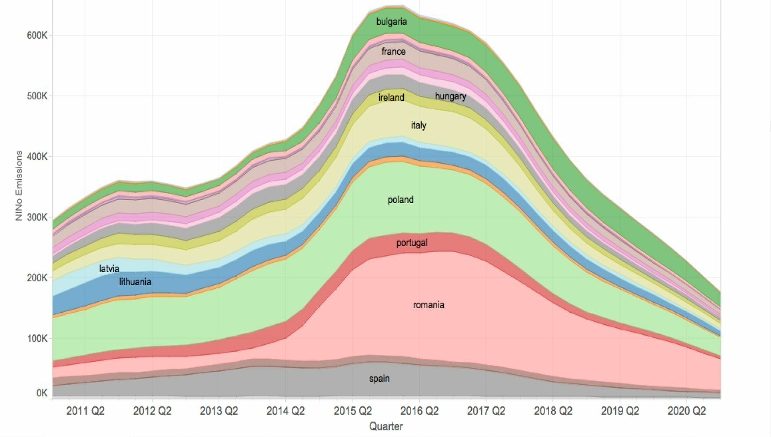

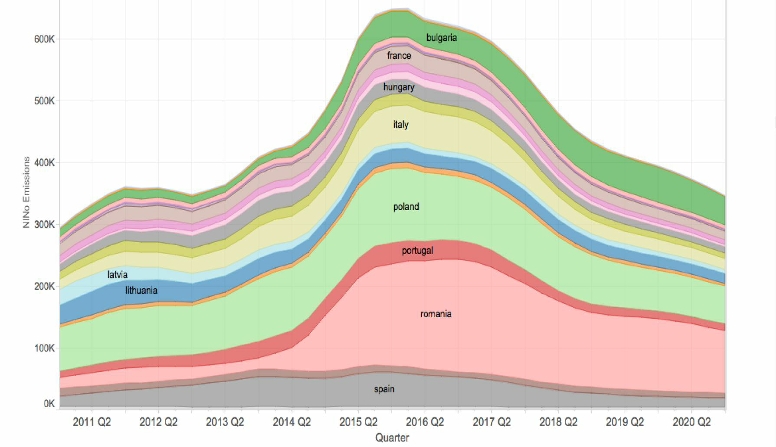

While speculation to date on the economic impact of Brexit has hinged on deteriorating trade, a fall-off in the numbers of migrants participating in the UK economy can have an effect of comparable magnitude. Two scenarios covered in the NIESR report – roughly matching a soft and a hard Brexit – would see net annual migration numbers fall by 91,000 and 150,000 respectively. Their impact on the UK’s GDP would then be a loss of between 0.6 and 1.2 per cent by 2020.

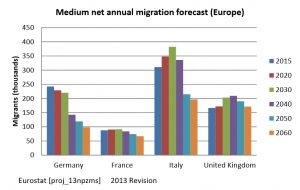

Falls in migration with time following a softer Brexit are more gentle compared to the headline graph above. Credit: NIESR

Last week, in Chief-Exec.com we looked at recent migration history and considered the social and economic effects associated with the decision in June for the UK to leave the European Union. Migration brings needed capacity and capability which domestic labour cannot supply. This was further demonstrated this week in a letter to the Guardian by 30 senior representatives of the food and drinks industry.

“The government should offer unambiguous reassurance to EU workers throughout our supply chain about their right to remain,” the industry wrote.

“If we adopt a work-permit system to control immigration, then the whole of our supply chain must receive equal treatment with financial services or the automotive sectors.”

Can insights on migration from the NIESR scenarios and forecast help resolve the legitimate concerns of the food and drinks industry, and those of many other sectors demanding to be heard?

The answer lies in the value of the forecast. A rule of thumb is that, counterintuitively, the most valuable forecast is one that is most surprising or risky and which also can be most readily challenged by evidence. It will rain at 2 pm today is a more valuable weather forecast than one predicting rain sometime next week. It can be easily rejected if it proves to be inaccurate and provides the most useful information if correct.

Any report or person predicting something that cannot be proven wrong is, at best, providing entertainment.

We can now apply this principle to the subject of migration.

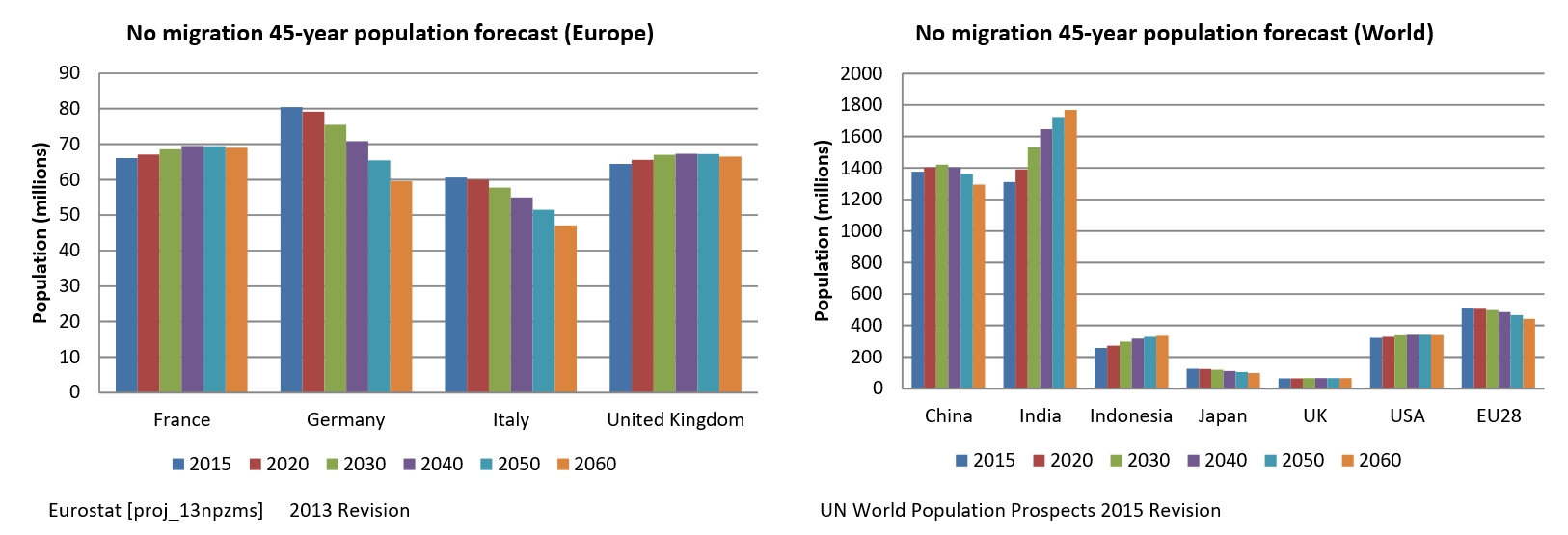

A least risky approach is to use population statistics that do not include migration at all. Assumptions then are only about fertility and mortality. These statistics are well understood and derive mainly from national healthcare systems. It is a low-risk starting point based on an unrealistic scenario that has limited value.

If one looks at major economies, a sample of which is shown above, over the next 45 years populations in developed nations in the absence of migration would generally be static or fall. In Europe, only Ireland (16 per cent), the UK (4 per cent) and France (3 per cent) show noticeable growth. Most other countries would have much greater falls and the EU itself would see its population drop by 12.7 per cent. Meanwhile, in Africa, the population will grow by 148 per cent, in Latin America by 28 per cent and in Asia by 22 per cent.

It is highly probable that Europe would have a static population in a very dynamic world. Also, individual European countries and markets will be minuscule in terms of their population.

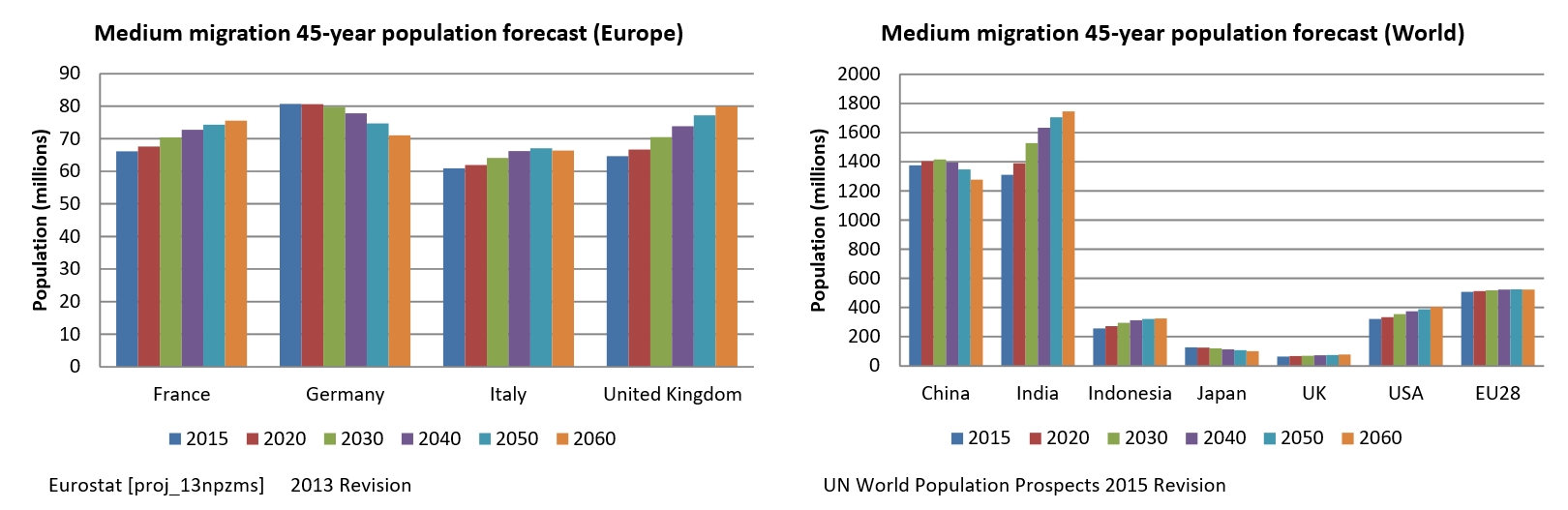

More valuable scenarios need to include assumptions about migration, which make their forecast inherently more risky. The UN World Population Prospects project makes its assumptions based on a wide variety of information sources listed in their meta-information pack.

The inclusion of migration assumptions shows that some developed nations will broadly compensate for their natural decline in population and some countries, including the UK, will have population growth restored.

For those who consider the British Isles already overcrowded, a predicted 12 million additional migrants by 2060 might make uncomfortable reading. These numbers are at least twice the government’s stated target of bringing migration numbers down to the “tens of thousands”.

Eurostat, the European Commission statistics agency, also has a reduced migration option, but the numbers in their main analysis shown above are comparable with an alternative scenario described in the NIESR report, which corresponds to their harder form of Brexit, with an assumed absence of free movement of European citizens into the UK by 2020.

The above scenarios provide a reasonably robust insight into future population numbers, as they are derived from relatively few assumptions. They can readily be adjusted in the light of new evidence.

The above scenarios provide a reasonably robust insight into future population numbers, as they are derived from relatively few assumptions. They can readily be adjusted in the light of new evidence.

It would be more valuable still to understand the opportunities and the costs of the above adjustments to migration. This requires more assumptions that essentially convert migrants into productive agents in their new country. Because of the complex nature of national economies, this translation is highly risky. Rational assumptions provide a useful best guess and, if validated, their forecasts can be valuable.

Using a direct conversion of a migrant as a unit of productive labour can lead to forecasts for the impact on GDP of the different migration scenarios. The complexities now are profound as migration issues become intertwined with trade, which itself is linked with business investment upon which GDP growth depends. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has provided a short-term forecast that is in line with other agencies in predicting a Brexit hit to UK GDP of about 3.3 per cent by 2020.

The NIESR analysis goes one step further, including further assumptions for the purpose of increasing valuable accuracy. As well as seeing the migrant as an economic agent, it also recognises “spillover” effects. Examples are competition for jobs increasing productivity and a side-effect of low-skilled migration encouraging the labour force participation of female workers.

Jonathan Portes, co-author of the NIESR report said: “Prior to the [EU] referendum, a number of analyses estimated the long-term impacts of Brexit on the UK economy; but none incorporated the impacts of Brexit-induced reductions in migration.

“Our estimates suggest that the negative impacts on per capita GDP will be significant, potentially approaching those resulting from reduced trade.”

Uncoupling the effects of migration on GDP could provide an extra lever to manage the UK economy through the Brexit turbulence.

If the UK citizen ends up worse off in 2020, early trade deals prove illusory and business investment dries up, then the British politician will have a lot to answer for.

If this is not the case, then some economic models which could have become valuable will simply have been candles in the wind.

By John Egan

In the long-term

Economist John Maynard Keynes famously said that in the long run we are all dead. The long run too is at the very end of the spectrum of risk and reward in economic forecasting.

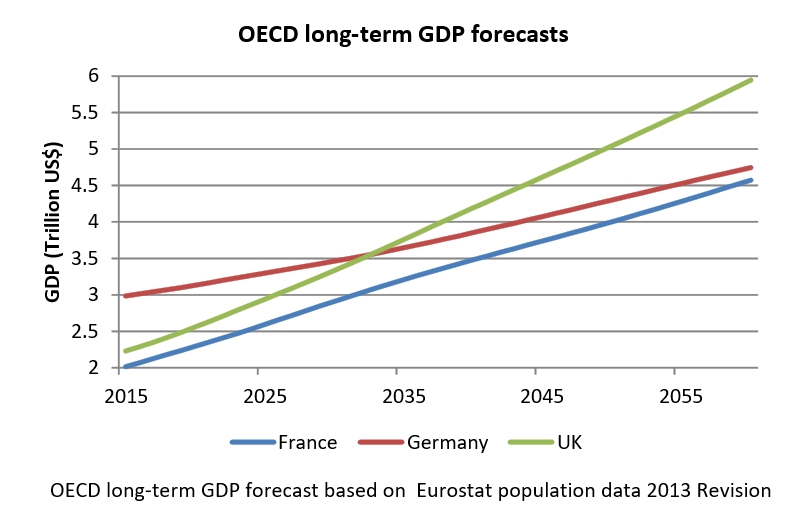

Long-term GDP forecasts that are available through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are conditional on a number of assumptions. Looking forward as far as 2060, their enormous depth of vision comes with a cost that it is almost certainly highly approximate. Economists prefer to refer to their long-term scenarios as “projections” to avoid an assumption of accuracy that “forecasts” tend to convey.

These long-term forecasts have regularly underestimated UK growth in recent times, partly because the current version originated in 2013 and does not include later waves of migrant arrivals. In any case, these fluctuations and possibly Brexit itself, would be a temporary blip on such a long-term projection.

Yet, we should not discount the longer term forecast too readily as within it there is a glimmer of hope for the UK economy. The OECD predicts the UK could have a healthy long-term growth through which, by 2033, the British economy (at $3.58 trillion GDP) just overtakes Germany to become the largest in Europe – all assumptions remaining as they were in 2013[1].

Unfortunately, by 2033 the UK GDP forecast will be dwarfed by those of China ($29tn), the US ($24tn), India ($13tn), Japan ($5.1tn) and Russia (4.3tn), and will soon also be overtaken by Indonesia and then by Mexico.

Speaking to Chief-Exec.com, an OECD spokesman pointed to some improvements being made to the long-term GDP forecasts. The methodologies behind projections for employment, capital stock and productivity are being revised to broaden the set of structural policy drivers, in order to better evaluate the potential long-term effects of policy reforms. It is likely that, when the new methodology is introduced – possibly in June next year – the long-term economic forecasts will be more useful and probably more pessimistic as they will incorporate the enduring effects of the global financial crisis.

Economic forecasting, particularly of unprecedented events, combines multiple assumptions with complex interdependencies, so that their accuracy may not be so good. However, despite the denouncement of expert brexitologists, to people needing to see on a dark night, a candle is still a valuable thing.

[1] This happens when measuring the size of economies at constant (2005) purchasing power parity exchange rates.