Not if drugs policy remains the domain of the UK government in London where a hard-line Conservative Home Secretary is reluctant to devolve the power, writes Murray Ritchie.

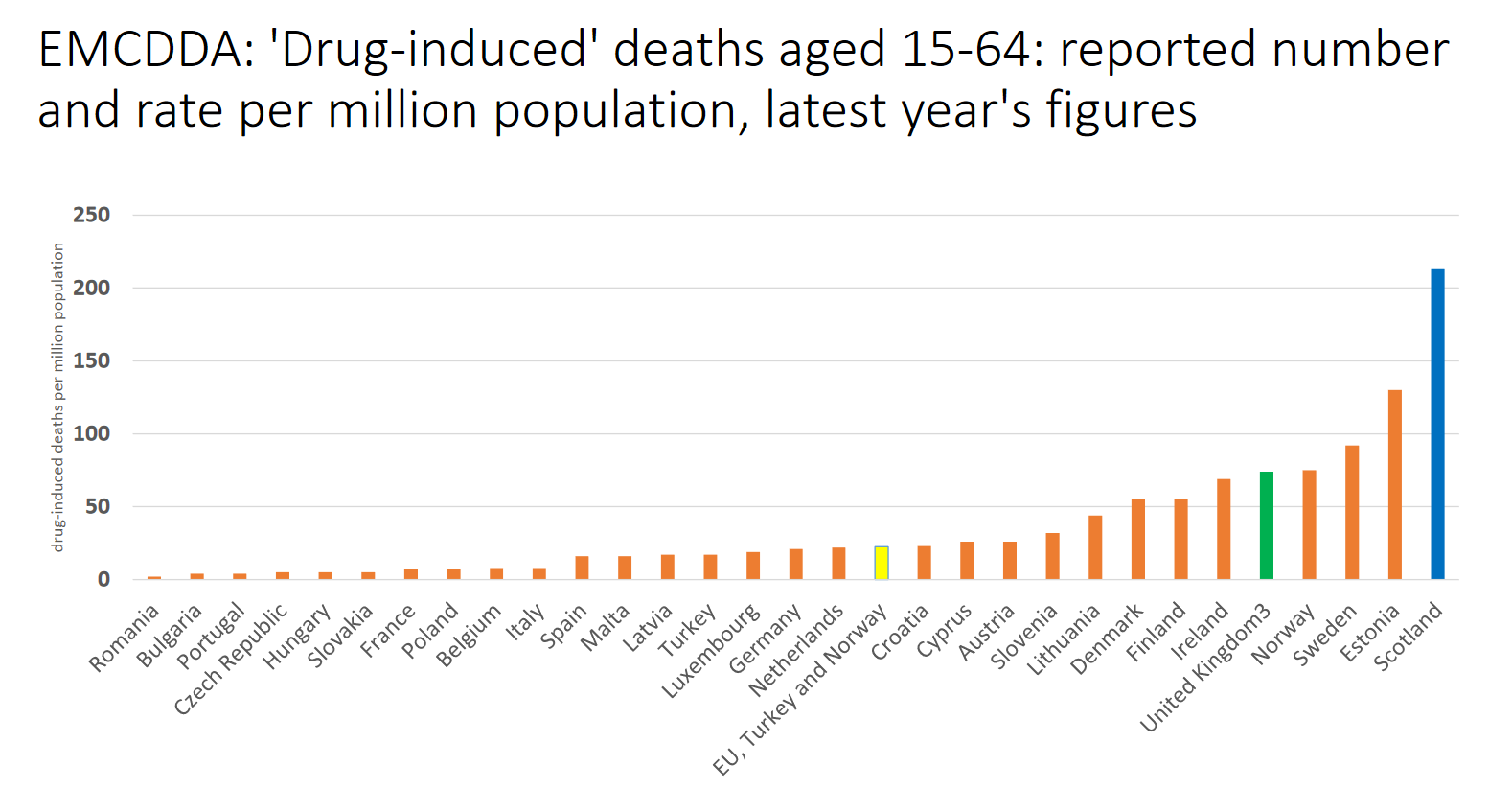

Scotland has the highest rate of drug-related deaths in Europe. The embarrassment is prompting calls for a change in the law, but politics is getting in the way. Is it too much to hope that Scotland’s shame might finally lead to an effective fightback in the losing battle against addiction and the worldwide social chaos it causes?

Several decades ago, a colleague of mine on the Glasgow Herald wrote a memorable feature predicting that drug abuse fuelled by crime was about to assume epidemic proportions in Scotland. At that time the police had only a small drug squad whose hard-pressed officers privately agreed.

There was hell to pay as politicians and senior police figures immediately protested that this was irresponsible exaggeration. But, tragically for Scotland, my colleague was proved right. Today, Scotland has the disgraceful distinction of standing top of the European table for drug deaths.

It’s not just Scotland. Around the world politicians are trying and failing to find an answer to this menace. They have tried persuading those tempted to “just say no” as if it were that simple. Some countries, notably the Netherlands, have tried legalising softer drugs like cannabis without great success.

All attempts to turn back the tide of social destruction seem to fail – all attempts, that is, with the exception of legalising hard drugs in controlled circumstances. And everywhere organised crime thrives on an epic scale, earning billions and overwhelming all international efforts at control.

Today, Scotland has the disgraceful distinction of standing top of the European table for drug deaths.

Sociologists can blame poverty, the police can blame crime, and everyone can blame politicians for being paralysed in the face of the illegal drug industry’s unstoppable progress towards social misery almost everywhere in the western world.

The only response that has not been tried in the United Kingdom is legalising the use of hard drugs under medical supervision in so-called consumption rooms. It is this idea which has attracted the interest of harried politicians in Scotland, desperate to lose their unwanted distinction for failure.

Might that idea work where everything else seems to have failed? We might never know because there is a problem. Drugs policy is the reserve of the UK government in London, where a hard-line Conservative home secretary is reluctant to devolve the power to experiment with such control measures to the Scottish National Party (SNP) government in Edinburgh.

You might think the enormity of the crisis would overcome party political rivalries. Well, not yet.

Data presented to Annual meeting of the EMCDDA expert network on Drug-related deaths, 2019

The urgency is compelling and the facts terrifyingly plain: in 2019 a total of 1,264 lives were lost to drug abuse in Scotland, a country of fewer than five and a half million souls. This figure was a record and more than twice the total of 10 years ago. It shows Scotland’s death rate from drugs is now worse than America’s, which is recognised as truly awful.

Not surprisingly there is a sense of dread prevalent in Edinburgh as politicians await updated figures from the Office for National Statistics next month. They will inevitably be even more depressing.

Meanwhile, Angela Constance, the new Scottish minister for drugs policy, is standing by with more than £14 million set aside for investment in facilities to give users legal access to treatment under medical supervision and some hope of remaining alive.

But changing the law requires updating Britain’s half-century-old Misuse of Drugs Act which leaves power in this area with the government in London. Priti Patel, the UK Home Secretary, is refusing to allow the Lord Advocate, Scotland’s most senior law officer, the right to legalise consumption rooms.

Most of those killed by drug abuse are so-called “poly-drug” users, taking more than one substance. Many of the drugs they abuse are fakes manufactured on a vast scale by crime syndicates happily prepared to sell deadly poisons masquerading as heroin or cocaine.

In some parts of Scotland, notably the city of Dundee which has the distinction of being the worst for deaths by drug abuse, it is reportedly common to find dealers and pushers hanging around school gates in search of new child victims. And that danger is not confined to Dundee.

A couple of weeks ago United States’ law enforcement officers conducted a major international sting which netted 800 criminals engaged in the drug trade. This was celebrated as a major success – which it was – in the war against organised crime. Yet everyone knows the death rate around the world will continue to rise. For every criminal arrested there are others simply waiting to join the trade. Changing the law to legalise hard drugs seems to offer the best chance of meeting the challenge.

The UK Home Secretary, is refusing to allow the Lord Advocate, Scotland’s most senior law officer, the right to legalise consumption rooms.

Scotland has reason to be proud in one respect when it comes to radical reform.

When the Scottish Parliament was established in 1999 one of its more radical moves by the then Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition government was banning smoking in pubs and restaurants. This bold move was met with cries of panic and protest by the drinks and catering industries. But it worked.

More cautious politicians in London waited to study public reaction before passing similar legislation. The UK’s health improved as smoking became less widespread.

Similarly with alcohol the SNP government in Edinburgh introduced minimum pricing for some drinks against much lobbying from interest groups. But alcoholism’s societal damage has been reduced.

Perhaps Scotland, for all its failure with drugs, would be on the right track again when, and if, the Edinburgh parliament is allowed to be radical.

Headline Photo Credit: vidguten/Shutterstock.com