The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) yesterday presented their analysis of how emerging digital technologies will profoundly disrupt the operations of global industry and commerce, reports John Egan from Paris.

Think of innovation as the act of making information valuable.

Think of the sale of a product via a stall, a salesperson or an internet platform. The one thing they have in common is that information is communicated to the consumer, be that through the product itself, the salesman’s banter or the images and specifications listed on a screen. The effect is the same – to enhance the consumer’s perception of value.

All products exist in a cloud of information that includes designs, material specifications, fabrication programmes, quality systems, regulatory compliance and marketing materials. In a restaurant the information is encoded into recipes and menus. Know-how is everywhere. Innovation brings value to this information.

Making a widget or cooking a meal is not innovation but production. Elsewhere on Chief-Exec.com we have proposed an approach to uncouple these two independent aspects of enterprise.

This might be an arbitrary and rather academic distinction were it not for the recent emergence of extremely powerful ways to process information. The internet of things, big data analytics, cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain technology (see below) combine and interact in ways that create a powerful ICT[1] toolbox for making information valuable.

Industries and societies that wish to be innovative will not only need access to this ICT toolbox, but also to employ the skills needed to use the instruments therein – skills that are in short supply.

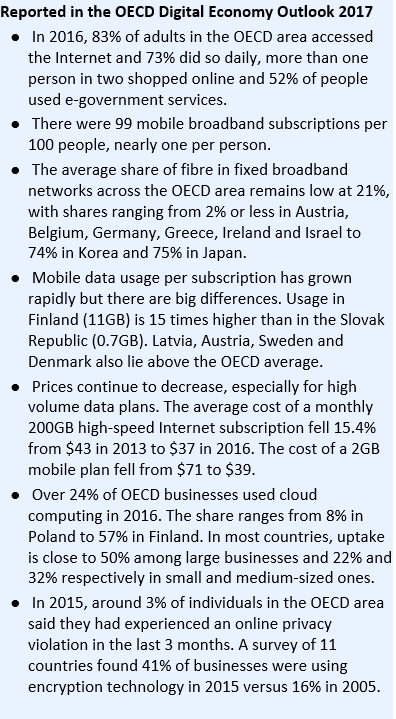

“The technology is moving so fast that we do not yet know where jobs will be lost and where new jobs will be created,” Dirk Pilat the OECD’s Science Technology and Innovation Deputy Director said yesterday, during the launch of the organisation’s biennial Digital Economy Outlook report.

Future skills will be different from those of today and individuals and organisations will need to be flexible to adapt to changing circumstances. They will, however, depend on strong foundations in literary and numeracy he says.

If the perceived risks prove to have a deepening social impact then a public backlash against a digital transformation is likely.

Some warn that risks also litter the emerging ICT landscape. Hackers, fraudsters, identity thieves, compromised privacy and intellectual property theft meet on the dark side with tax avoidance scams and child abuse.

“There is no such thing as absolute security. Businesses, particularly SMEs, and individuals need to introduce or improve their digital risk management practices”, Dr Pilat told those gathered at the OECD Global Parliamentary Network that coincided with the launch of the report. The meeting of 65 members of parliament from 25 countries voiced concerns over the potential abuses emerging from unregulated developments of global ICT infrastructure and systems.

Global Parliamentary Network: legislators from 25 different countries discuss their ITC concerns. Credit: OECD

The French deputy of the European Parliament, Robert Rochefort, told Chief-Exec.com that the big challenge for parliamentarians is to convert the OECD recommendations into effective legislation so the full benefits of the advances in ICT can be realised.

If the perceived risks prove to have a deepening social impact then a public backlash against a digital transformation is likely, as has been seen more generally in reactions to unfavourable societal outcomes of the globalisation of commerce.

So what does this means for innovation?

Of course innovation walks hand-in-hand with risk, as has always been the case. But it is important to recognise where the risks lie in the emerging technologies and, on this, the OECD report provides an illuminating insight.

Take blockchain technology for example.

Blockchain is a “distributed and tamper-proof database technology that can be used to store any type of data, including financial transactions, and has the ability to create trust in an untrustworthy environment”, according to the report. Rather than relying on centralised databases of trusted intermediaries, such as credit card providers, a blockchain relies on a distributed peer-to-peer (P2P) network for storage and management of data. Users cannot delete data and all amendments are rigorously recorded. The digital currency Bitcoin which today soared to a $5,000 record high, is an example of this approach.

Blockchains also come with the capability to execute software programs encoded into “smart contracts” and execute these in a decentralised manner. Because there is no central operator responsible for running the code, such applications are guaranteed to provide users with significant levels of security assurance and anonymity. The technology can reduce market friction and transaction costs and increase the efficiency of existing information systems by eliminating multiple layers of administrative intermediaries.

But, who do you go to if something goes wrong? Where does legal liability lie? How can regulations be imposed in such decentralised environments?

The list of questions is only just being drafted.

Another question: does blockchain technology present the first step in the demise of the old-fashioned nation state and what, then, may happen to private property rights? No doubt a distributed database is just what is needed to ensure their protection.

[1] Information and Communications Technology

Headline Photo Credit: Zapp2Photo/Shutterstock.com