Anthony Albanese, Australia’s 31st prime minister, is offering a different kind of politics, starting with inclusion not division, writes Geoff Kitney in Canberra

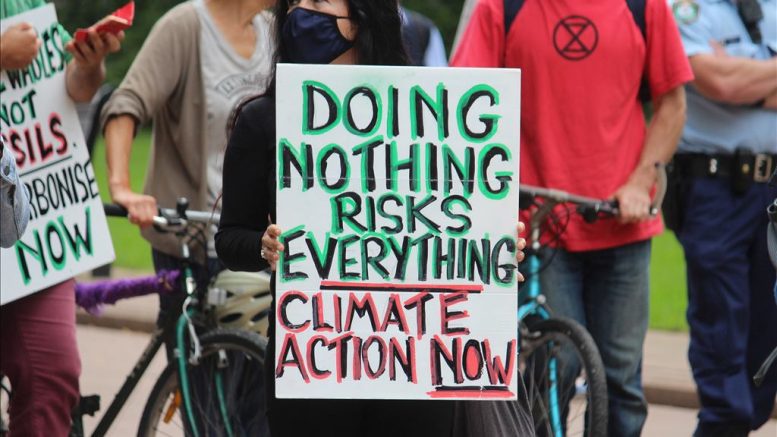

The elephant in the room that Australia’s political leaders have tried not to notice has just crashed its way into their lives – and transformed politics.

After a tortuously long and dull general election campaign, Australians voted on Saturday for a new political order in which the issue of climate change will demand a response to deal with the reality of its growing impact on the lives of ordinary Australians.

Australia has been smashed repeatedly by climate change-linked natural disasters in recent years – from devastating bushfires to catastrophic, record floods. Climate scientists say Australia – the world’s driest continent – will be at the forefront of the devastating impacts of climate change.

But the major political parties have struggled to come to terms with the demands of climate change. With the world’s third largest resources of fossil fuels and powerful corporate interests – including those of billionaire media tycoon Rupert Murdoch, owner of two-thirds of Australia’s print media – the traditional parties have resisted the policy changes that would impose costs on the sector. The policies needed to help mitigate the shattering impacts of a warming planet on this ancient continent have rarely been forthcoming.

On Saturday, Australian voters delivered a thumping defeat to the centre-right coalition government of Prime Minister Scott Morrison but gave his Labor Party opponents a qualified victory. Huge swings went instead to the Greens and a raft of independents whose major focus was on the need for Australia to act on climate change.

One of the first and biggest tests of the new government will be how it responds to the challenge it now faces to adopt bolder and more ambitious action on climate change.

Labor has bitter memories of an earlier attempt to take bold climate action when it introduced a carbon tax – leading to a landslide election defeat and nearly a decade in the wilderness.

But today’s Labor government at least starts from a base of accepting the realities of climate science – in contrast to the Morrison government which included leading climate change deniers and was determined to put the interests of the fossil fuel industry first.

Labor says it is committed to net zero carbon emissions by 2050 but it is still likely to struggle to balance the electorate’s demands for stronger climate policy measures with the interests of workers in the resources sector and its timidity in the face of Murdoch-led media campaigns opposing climate action.

This, however, is just one of a daunting list of challenges facing the new government, one that is likely to govern with a slim parliamentary majority.

Labor is facing a transformed political landscape in Australia

Saturday’s vote saw support for the major parties (the Liberal-National Party coalition and the Labor Party)– which have dominated Australian politics since the second world war, shrink to record lows. A third voted for other parties and independents. Labor won despite losing around two per cent of their vote from the previous election. The coalition parties lost nearly six per cent.

The new parliament – which will sit for the first time mid-year – will include up to 16 MPs (in a parliament of 152 seats) not from the major parties and sitting on the cross-benches.

Every seat the government lost was to a woman. Nearly half the new MPs are from ethnic backgrounds.

Nearly half of the new MPs are what have been dubbed “teal independents” – because they advocate a mix of policies from across the political spectrum. All are women. This will be the most diverse Australia Parliament ever.

This was another feature of this election – women voters asserting themselves in an unprecedented way.

It was a reaction to the deeply conservative, traditionalist (and in several cases, Christian conservative) views of Prime Minister Scott Morrison and much of his Cabinet, and to a high level of tolerance by the government of shady dealings. Integrity was a major issue in the election campaign, with Labor promising to set up an “integrity and corruption commission” to investigate possible crimes by members of the outgoing government and its financial backers.

Concerns about that lack of integrity was a big factor in why the main partner in the conservative coalition – the Liberals – had its historic base in the wealthy inner cities of Melbourne and Sydney – smashed by the “teals”.

The Liberals face a crisis of identity with a large part of its more moderate “small-l” base deserting it.

Labor also saw swings against it in its traditional “blue-collar” areas – in part because of perceptions that it was embracing “elitist” centre-ground policies, such as on climate (complicating its challenge to adopt bolder climate change measures).

‘I want to seek out common purpose and promote unity and not fear. Optimism, not fear and division’

Anthony Albanese in his victory speech as prime minister-elect

But Labor’s leader – and now Prime Minister of Australia – Anthony (Albo) Albanese is very much from a traditional Labor background. He is a son of the working-class. He grew up with his single mother in public housing and had to overcome social disadvantage to go to university and pursue a professional career.

Albanese promised in his victory speech to be a leader who will “bring Australians together, no matter what their background” – a message calculated to appeal to voters tired of nine years of right-wing conservative government which has encouraged in Australia culture wars similar to those seen in the United States. Morrison was a Donald Trump fan.

Albanese immediately gave substance to this promise by announcing that his first priority would be to give Australia’s most disadvantaged citizens – its indigenous first inhabitants – a right to have a special voice in the nation’s affairs. A move that would require a Constitutional referendum to include that recognition in the Constitution.

Domestic challenges are just part of the huge task ahead

Immediately, there is the challenge of combating the significant rise in Covid cases.

From being one of the world’s most successful countries in dealing with Covid, Australia now has one of the highest infection rates. Leading up to the election, the Morrison government effectively abandoned containment measures, judging voters were deeply weary of the onerous measures that had contained the disease and embracing the UK government’s message that it was time to restore “freedom” to people’s lives.

Albanese’s government also faces some tough decisions, including dealing with the on-going economic fall-out of the Covid pandemic, particularly historically high public debt and out-of-control public spending. Rising inflation and a suddenly much riskier international economic environment will force the new government to bring down an early budget later this year.

Nearly two-thirds of Australians now say they see China as a potential danger to Australian security

Defence and strategic policy also confront the new government with some early tests. Geo-political upheavals have made Australians feel much less safe.

Australia’s relationship with China has become highly problematic. China is by far Australia’s largest trading partner: It takes a third of all Australian exports. But – in part because of the Morrison government’s embrace of then US President Donald Trump’s decision to turn China from strategic partner into a strategic rival – relations with China have chilled dramatically. China has punished Australia by cutting off some vital areas of trade (although not resources, which are the overwhelming bulk of that trade).

Scare mongering by some conservative politicians about China as a potential military threat to Australia has caused alarm. Nearly two-thirds of Australians now say they see China as a potential danger to Australian security.

Labor has promised to try to improve relations with China – a commitment which the Morrison government used to try to brand Labor as a friend of China and willing to sell out Australian security. Morrison government ministers claimed during the election campaign that the Chinese leadership would celebrate a Labor victory.

Labor faces a difficult balancing act

China trade is vital to the Australian economy but China has made clear that it intends to aggressively assert itself in the Asia-Pacific region in rivalry to the United States, Australia’s major security partner. The US wants Australia to play an increasingly active part in its efforts to counter China diplomatically and militarily as part of the recently activated AUKUS strategic alliance between the US, the UK and Australia.

Albanese’s first act as Prime Minister will be to attend a meeting of regional leaders, chaired by US President Joe Biden, in Tokyo tomorrow at which China will be the main focus.

Despite what is clearly a big agenda of challenges left to him by the Morrison government, Albanese told voters in his first speech as prime minister-elect: “I want to seek out common purpose and promote unity and not fear. Optimism, not fear and division. It is what I have sought to do throughout my political life and what I will bring to the leadership of our country.”

Every seat the government lost was to a woman. Nearly half the new MPs are from ethnic backgrounds

With a parliament of unprecedented diversity and with his room to move limited by the narrowness of his victory, Australia’s 31st prime minister will need to be a consensus builder and a diplomat. His greatest strength will be that he seems already to recognise the immensity of the task and the need to be a builder, not a divider.

Headline image credit: Rose Makin/Shutterstock