The UK and Australia may have signed a free trade agreement but how deep does the idea of shared interests run? Geoff Kitney takes a look.

All sorts of spin have been put on the recent signing, in principle, of a Free Trade Agreement between the United Kingdom and Australia.

Most of it has little to do with the contents of the actual document. That is still a secret and there are still hurdles to be surmounted before the deal is signed, sealed and delivered.

But some observers – British and Australian – say that doesn’t matter. They believe that the actual contents of the agreement are less important than the fact of the agreement itself and the message it sends.

At the most practical level, the UK-Australia FTA – despite its very limited economic significance for either country – is symbolically important as the first post-Brexit new trade agreement to be negotiated with the UK. That’s because Australia was so keen to help out “the mother country” it was like an FTA negotiation on training wheels for the UK.

“I think it was a great learning experience for a country that, during the decades of its membership of the EU, did not need to negotiate trade agreements,” one Australian official, who asked not to be named, told Chief-Exec.com.

“British officials had to gain experience quickly and what better way to do that than with a country keen to help. This will help with the much more important trade negotiations to come.”

In fact, Australia had a direct hand in assisting the UK to develop the trade negotiating expertise which it has deployed since Brexit to develop the skills to do FTA deals. Several Australian trade specialists – including a former trade minister, Craig Emerson – were hired as consultants.

But look beyond how the UK-AUS FTA deal was done and what the agreement contains and you see something much more interesting. What you see is what this agreement says about the mind-set of the two countries.

Both the UK and Australia have long been, and continue to be, uncomfortable in the regions in which they exist.

Of course, the UK is different in that it has done something very concrete about this discomfort. It has withdrawn from the neighbourhood – at least in every sense except actually tying itself to some giant cosmic force and getting towed to another part of the world.

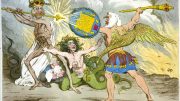

The decision to Brexit emphatically confirmed the truth that the UK – or at least the current Conservative government – saw itself as not being part of Europe. The clarion call of the Brexiters to the British people was to seize this glorious opportunity to escape from the clutches of the gnomes of European collectivism and for the UK to strike out on its own, offering itself as a symbol of freedom and self-determination.

Actually, the “truly global Britain” that the leading Brexiters had in mind was something less than this suggested.

Whereas the UK responded to its discomfort with the EU by quitting its membership, Australia is responding to its discomfort with its region by signing up to a multi-national grouping of like-minded nations.

Even before Brexit was completed, strong voices in the Conservative Party began talking about the need to revive the so-called “Anglosphere” – a multi-national entity made up of the major English-speaking nations – the UK, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Leading Australian conservatives – including two former prime ministers – eagerly signed up to this idea. One of them, Tony Abbott (who was born in the UK, is a passionate Monarchist and hardline conservative) even volunteered to go to London to offer his trade policy expertise to the Johnson government.

The Anglosphere is seen by its members as a natural alliance between five nations not just with a common language but also with shared histories, some springing from the British colonial era.

It also was seen as giving a shared political voice to the so-called Five Eyes intelligence sharing network. This has existed for decades, but has been elevated to new relevance by the rise of China and the concerns each of the five powers has about the challenges posed to Western democracy by an ever more assertive China.

Both the UK and Australia have long been and continue to be uncomfortable in the regions in which they exist.

Australia’s trade with China – which represents 40 per cent of its total trade with the world – has suffered a series of blows that have been seen as deliberate punishment by China for eagerly supporting recent harder line US policy towards China, leaving Australia feeling vulnerable and exposed. For Australia, the Anglosphere and the Five Eyes have suddenly had new appeal as its relationship with China has turned seriously sour.

So, whereas the UK responded to its discomfort with the EU by quitting its membership, Australia is responding to its discomfort with its region by signing up to a multi-national grouping of like-minded nations.

And, whereas the UK’s departure from the EU and its plunge into the unknown is now irreversible for the foreseeable future, Australia’s move towards deeper, formal connection to the Anglosphere is a work in progress.

And there is a growing chorus of voices – including a former Australian foreign minister Bob Carr and a one-time Ambassador to China, Geoff Raby – which has been critical of what they see as Australia’s decision to turn back to its British colonial past in these more troubled times.

They argue that Australia cannot deny its geography and the reality that its most important relationships ultimately have to be within the Asian region of which it is part. They say that Australia’s Asian neighbours see Australia’s Anglosphere shift as a grab for a “racialised identity” that harks back to the White Australia policy which required post-war immigrants to be of “European stock”.

Critics argue that Australia’s long-term interests are in its region not – as one former senior diplomat (who spoke on background) put it – “any entanglement what-so-ever with a ridiculous political confection as the Anglosphere represents”.

The odd thing about all of this is that it seems to be Britain’s decision to cut itself away from the EU that has added to Australia’s confusion about where its best strategic and economic interests lie.

The discomfort Australia feels at its geography and how this sense of “not belonging” undermines its vital interests was highlighted recently by the publication of data which showed that Australian politicians rarely visit Asian countries compared to visits to Israel or the US. The most frequent visitor to the region was a government MP who had a girlfriend in the Philippines.

This is despite the dynamic economic growth of many of Australia’s near neighbours which is seen as offering huge potential for Australian trade and investment but which businesses show only limited interest in exploiting. Reflecting this, the proportion of Australian students studying Asian languages has been in free-fall. Analysts say the same trend has been apparent in the UK with European language studies in long-term decline.

The odd thing about all of this is that it seems to be Britain’s decision to cut itself away from the EU that has added to Australia’s confusion about where its best strategic and economic interests lie.

For Australian conservatives, who have always looked to Britain for their inspiration and who fought doggedly and successfully to stop Australia becoming a republic and retaining the Queen of England as the Australian head of state, there has been a sense that Australia should do all in its power to support the UK during and after the Brexit process.

The idea of an Anglosphere was seen as a way to bring to the aid of ‘the mother country” all its English-speaking offspring. As a “family” with a shared history, they argue, the five Anglo nations can work together to defend the interests of the English-speaking democracies in an increasingly uncertain and dangerous world.

But one of the strong critics of the Anglosphere/Five Eyes arrangement – former Australian Ambassador to Beijing Dennis Argall – pointed out in a recently published article for the Australian policy website Pearls and Irritations: “There is already evidence that Australia’s partners in the Five Eyes sleuthing cabal have replaced many of Australia’s blocked exports to China. All of this spy gang to which we belong, except Australia, maintain high-level contact with China.”

So how deep does the idea of shared interests run and what are the risks compared to the benefits?

These are major questions so far not satisfactorily answered.