With approval ratings as high as 90 per cent Australia’s state leaders and the parties they lead look set to reap the rewards of keeping their communities safe, writes Geoff Kitney.

While the Covid pandemic has posed tests of political leadership that many have failed – some disastrously so – there are a few who have risen to stratospheric heights of popularity.

Unheard of levels of approval from voters for policies which have kept Australia remarkably free of the tragedy and misery of the Covid pandemic have propelled political leaders here to unprecedented levels of approval from their voters.

Over the vocal objections of a minority of critics of tough policies which have effectively strangled the ability of Covid to spread widely through the community, leaders of Australia’s state governments have been able to boast of having done more than most leaders around the world to keep their communities safe.

Approval ratings in opinion polls as high as 90 per cent have set up state leaders and their political parties for near certain victories at coming elections – and quite possibly elections beyond.

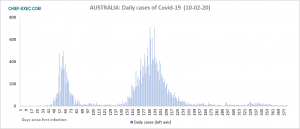

The Australian death rate per 100,000 people is just 3.7 compared to 158 in the UK and 134 in the US.

Where state governments have applied policies aimed at eliminating Covid rather than simply suppressing the virus, long periods without any infections have seen local economies doing much better than places where Covid-control policies were not as forcefully applied for fear of the economic damage that might have resulted.

The Australian experience has come to the attention of the world in recent days with the opening of the Australian Open Tennis Championships – one of the five “Majors” – on February 8 with crowds of up to 30,000 – a prospect few countries in the world could contemplate.

The back story to this is that the event will take place in Melbourne, capital of the state of Victoria and Australia’s second largest city. Melbourne is also the city with Australia’s worst Covid record. Eight hundred and twenty of Australia’s total Covid death toll of 909 occurred in Victoria, as have more than 20,000 of Australia’s total infections of just over 24,400.

When Covid was first diagnosed in Australia in March last year, there was intense discussion about how best to respond – by striving for suppression or seeking complete elimination.

The case for elimination was based on the belief that, as an island nation with the potential to strictly control its borders, Australia could keep Covid at bay with strict limits on who could come into the country.

There were conflicting views about this among Australia’s various levels of government. The national government – a centre-right political coalition of Liberal and National Party members – believed that suppression was preferred, as the measures to achieve elimination would impose too great a cost on the economy.

The state and territory governments – a majority of which are run by centre-left leaning Labor Party governments – favoured trying to achieve elimination.

Australia closed its international borders to all but Australian passport holders on March 20 last year, with those permitted to enter required to undergo 14 days in supervised quarantine in designated international hotels and permitted to leave only after a negative Covid test.

The national government was confident that, by excluding most foreign travellers, Australian health authorities could manage to suppress levels of Covid infections in the Australian population without resorting to harsher measures.

But a major breach of the border restrictions by Covid-infected passengers from a cruise ship which docked in Sydney in late March plunged the major political forces into a fundamental disagreement.

Several state governments moved to close their internal borders with neighbouring states – despite doubts about the constitutionality of border closure by state governments.

Steady progress in suppressing Covid infection rates followed before a second major outbreak erupted in Melbourne in early July, after a breach of security at a designated quarantine hotel.

The Labor state Government responded with the strictest lockdown measures adopted anywhere in Australia. It declared that the lockdown would continue until 28 days after the last Covid infection had been detected. Almost all activity – community and business – was forced to cease for the next 111 days.

Melbourne back in lockdown after outbreak

Melbourne, Australia’s second largest city, will plunge back into strict lockdown after more failures within the pandemic hotel quarantine system which the UK is adopting. A system modelled on Australia’s 14-day mandatory hotel quarantine for overseas arrivals is due to begin in the UK on Monday but rising fears about the ability of Covid-19 to rapidly spread through poorly ventilated hotels has triggered a re-think in Australia. Daniel Andrews, the Premier of the state of Victoria, warned on Friday that he was moving to end hotel quarantine in Melbourne, the state’s capital, all together or limit overseas arrivals to only compassionate cases. “I’m making it clear to you that I’m looking at hotel quarantine and whether it can be done at an acceptable risk level. And I don’t think I’ll be alone in doing that,” he told reporters after announcing the south eastern state of 6.2 million would enter a five-day hard lockdown from midnight on Friday (1pm GMT). The Times, February 12

The state Government’s draconian policies to eliminate Covid precipitated a major political conflict between centre-left parties supporting the action and centre-right parties opposing it. The national government, business leaders and media commentators argued that the Victorian government’s actions smacked of panic and would be economically disastrous. Others argued that the lockdowns imposed authoritarian rule on citizens, forced at the behest of unelected bureaucrats and medical experts. Political tensions soared.

But while politicians and their supporters argued, the rate of Covid infections steadily declined. By late October, Victoria had no community transmission of the virus. Since the effective elimination of the virus in that state, only a small number of infections have been detected anywhere in Australia. When they have been, governments and health authorities – using advanced track and trace systems – have managed to quickly isolate and control the outbreaks. States which closed their borders when infections were detected in other states have seen their economies performing to almost normal levels. Australia’s unemployment rate has quickly moved back towards pre-Covid levels.

Not all sectors have been so lucky. Industries reliant on international tourism have suffered, although the lack of Covid inside Australia has seen a boom in domestic tourism. The higher education sector has suffered because international students – who provide a large slice of income for Australian universities – has also been hit hard. Border closures have imposed hardship on families cut off from each other – including about 40,000 Australians still stuck overseas and prevented from returning by strict quotas on the numbers allowed to enter the country.

The case for elimination was based on the belief that, as an island nation with the potential to strictly control its borders, Australia could keep Covid at bay with strict limits on who could come into the country.

Most Australians not only feel fortunate to have avoided the consequences of out-of-control infection rates such as those in the United States and the United Kingdom, but also feel that Australia has set an example for the world.

The most recent World Health Organization figures show that Australia’s Covid infection and death rates are close to the lowest in the developed world, with neighbouring island nation, New Zealand, doing slightly better.

The Australian death rate per 100,000 people is just 3.7 compared to 158 in the UK and 134 in the US. Sweden – a country with a relatively small, widely spread population which preferred to seek herd immunity – had a death toll more than 10 times Australia’s, at 116 per 100,000.

Australian authorities remain vigilant for the danger posed by outbreaks from quarantine hotels – the potential entry point for the new Covid variants in the event of a breakdown of the quarantine system. A case last week of an infected worked from a Melbourne quarantine hotel – which threw a scare into preparations for the Australian Open tennis – highlighted this risk and resulted in an immediate decision by governments to review the arrangements and limitations imposed on the hotel quarantine system.

I have just spent three months in Perth, the capital of Western Australia, where there were no Covid infections for 10 months. Life in Perth was almost as normal as pre-Covid. A few days after I left Perth a case of the UK variant of Covid was detected in a worker in a quarantine hotel. The state Government reacted by imposing an immediate, total lock-down for five days and mobilised its track and trace system to detect any further community spread. None were detected and the state economy began to re-open five days later.

A West Australian government spokesman said that state Premier Mark McGowan believed his state’s record had shown that setting the goal of eliminating Covid had proven to be the best way to protect the lives of citizens and the local economy. Trying to balance Covid numbers with a degree of economic openness had proven disastrous elsewhere, he argued.

With community spread of Covid currently non-existent in Australia, Australian authorities have breathing space to begin a national vaccination program, which has allowed them time to assess the initial results from Covid vaccination programs elsewhere.

The elimination of community spread has also meant that Australia is well placed to deal with the threat of Covid variant infections which threaten to overwhelm health systems elsewhere.

Australian health workers say they feel fortunate compared to those in the UK and the US and other countries where Covid has run out of control. “We are very glad we don’t have a Boris Johnson or a Donald Trump in charge in Australia” is a refrain widely heard among Australian health workers.

Headline image credit: Dave Hewison Photography/Shutterstock.com