When Novak Djokovic took up residence at Melbourne’s Park Hotel for a few days, the world noticed the desperate refugees locked in with him. But he has left the building and the media scrum has moved on, writes Geoff Kitney from Canberra.

Australia has a dirty little secret. Or at least, it did until the world’s number one tennis player, Novak Djokovic, fell foul of Australia’s hard-as-hell border security system.

Few outside Australia – and perhaps not that many inside the island continent – knew about the Park Hotel hell in which Australia holds a group of political prisoners. Well, actually, inadvertent political prisoners who made the mistake of thinking Australia would be a safe place to go to escape war and deprivation in their own countries.

Some have been “imprisoned” for nearly a decade, since they arrived in Australia on small boats operated by people smugglers making profit from their plight.

Australians mostly prefer not to think about these people.

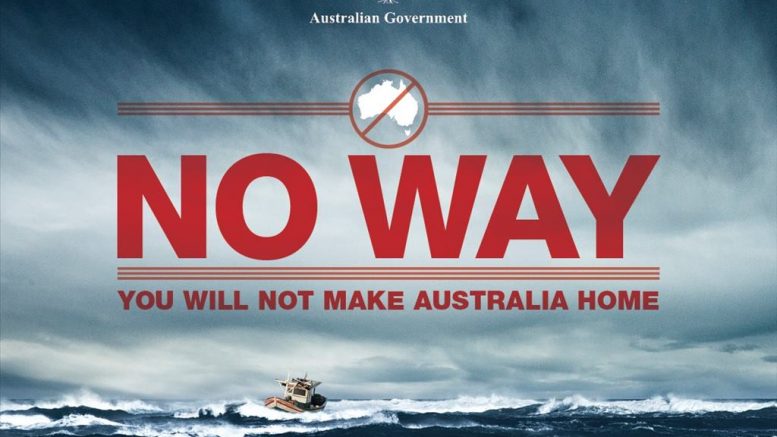

The policy of locking up asylum seekers (mostly Muslims) who dared to try to enter Australia by unconventional means – and keeping them locked up indefinitely despite being judged to be genuine refugees – has been seen as necessary “to keep Australia safe”.

“We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come,” is a slogan which has helped conservative governments stay in power in Australia for most of the past 25 years.

The same hard-line border protection philosophy applied to asylum seekers was applied from the start of the Covid pandemic. Australia chose to use its unique geography to protect its population from a Covid invasion by erecting virtually impregnable borders since the first Covid cases began emerging two years ago. Even Australian citizens abroad were shut out of their own country.

Most Australians supported the policy.

Novak Djokovic ran smack-bang into that hard border when he arrived in Melbourne on January 5, ready to play in the Australian Open tennis championship, starting today.

When border officials decided that his paperwork fell short of what they deemed was required to be given a medical exemption to enter Australia they cancelled his visa and threw him into the “immigration detention facility” which is the Park Hotel – a non-descript building in a nondescript part of Melbourne.

With huge international interest in Djokovic’s plight, the world’s media descended on the Park Hotel, to be greeted by desperate faces pressing against windows in the rooms surrounding the one in which Djokovic was being held.

They grabbed the chance to try to draw attention to their plight. For a few days, the world noticed them.

But the Australian government showed not the slightest interest. It stuck to its unwavering view that no-one who enters Australia via “illegal” means will ever be allowed to settle in Australia.

They remain “detained” with the only chance of release being to return to their homelands (impossible for most of them) or find a third country to take them, which many have done, but some have found impossible to find.

None of Djokovic’s fellow inmates have the resources to mount expensive legal challenges, as he was able to do.

It was only because of the hiccough in the processing of Djokovic’s visa paperwork that anyone other than the handful of activists who campaign constantly on behalf of the locked-up asylum seekers that the existence of this facility and its inmates would have become a subject of news and public interest.

The tragedy of this saga is that the brief flurry of interest in the plight of Australia’s imprisoned asylum seekers will change nothing for them.

Local media interest in the story was only ephemeral.

As Djokovic flew out of Australia – possibly never to return – after an Australian court concluded that the Minister for Immigration had the absolute power to cancel his visa and deport him, the streets around the Park Hotel were vacated by the media pack as the story moved on.

The bigger story – as far as most public interest was concerned – was how the Australian government took two weeks to fumble its way through arcane bureaucratic processes to finally achieve its goal of removing Djokovic from the country. Australians overwhelmingly wanted Djokovic thrown out.

Initially the Australian government seemed not to appreciate how strong this sentiment was.

When Djokovic arrived at the Australian border late at night in early January, the government was preoccupied with a rapidly growing Covid-related political crisis.

Australia chose to use its unique geography to protect its population from a Covid invasion by erecting virtually impregnable borders since the first Covid cases began emerging two years ago

After setting an example for the world on protecting its people from the ravages of the Covid pandemic, Australia was suddenly flailing in the face of a massive surge in Omicron infections.

The election in October last year of the right-wing libertarian, Dom Perrottet, to the office of State Premier for New South Wales, set in train a series of events which led to a decision – on December 15 – to remove all Covid-related health restrictions in that State.

The move was given full endorsement by the conservative Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, and Australia’s previously locked-tight international borders were declared open. Other states had little choice but to follow NSW.

When Perrottet came to office, Australia had had just over 230,000 cases, 1,590 deaths and 28,573 active cases since the pandemic started two years ago.

On the day that Djokovic arrived at Melbourne airport, in the state of Victoria, the number of Covid infections had soared to more than 612,000 with nearly 2,300 deaths and almost 300,000 active cases.

The positive infection rate of people tested had jumped from less than one per cent to around 40 per cent. Australia’s infection rate per one million of the population was suddenly the highest in the world.

Perrottet and Morrison had opened up after declaring that it was time for Australia to “start living with Covid”. They argued that the months of lock-downs and health restrictions had been too damaging to the economy and that Australians wanted “their freedom back”.

Morrison said it was time to change from “don’t do government control” to “can-do capitalism”.

Their decision to open up Australia was strongly opposed by many health experts who warned that the decision was reckless given the arrival in Australia of the new Covid variant, Omicron. The two leaders said they were confident Omicron and its potential impacts on the health system and the economy could be managed.

They were wrong.

What seems to have been utterly overlooked by libertarians – in Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and elsewhere – who have been screaming for Covid restrictions to be lifted for the sake of their economies is that public health and the economy are inextricably linked

Australia was simply not prepared for the Covid wave which it had so successfully held back for two years.

With only a small percentage of the population double vaccinated and having had their booster, infections spread like wildfire through the jabbed and the unjabbed.

Covid testing facilities were overwhelmed. Hospital systems came under strain.

Mass absenteeism from workplaces – either through illness, isolation or waiting in endless queues to be tested – smashed supply chains and caused businesses to either shrink their services or close.

The large government subsidies paid to businesses and emergency support paid to workers that had been the key policy response to previous Covid waves was gone. No assistance was available in this new “live with Covid” world.

One business spokesman said: “We are in a quasi-lock-down and it is far more damaging than the real thing. The economy is being smashed.”

“Living with Covid”, critics said, had become “dying with Covid”. The freedom ideology which underpinned the decision to allow Covid to run free in Australia was killing people.

What seems to have been utterly overlooked by libertarians – in Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and elsewhere – who have been screaming for Covid restrictions to be lifted for the sake of their economies – is that public health and the economy are inextricably linked.

The Covid mess into which Australia has plunged has big political implications.

A general election is due by May and the Morrison government has only a slim majority. It needs favourable political circumstances to give it a chance. But its poll ratings and the Prime Minister’s approval ratings are sliding.

After initially showing little interest in whether Djokovic came to Australia or not, the decision by Border Forcer officers to cancel Djokovic’s visa animated Morrison.

Border protection and his government’s hard-line policies to keep unwanted visitors out had been a political winner for the conservative parties.

The possibility that Djokovic had tried to con his way into Australia and could pose a threat because he had refused to be vaccinated offered Morrison the opportunity to create a distraction to his government’s mishandling of the “living with Covid” changes.

“Rules are rules,” he said almost triumphantly when Djokovic was taken into custody and moved to the Park Hotel. “No-one is above the law in this country.”

As things turned out, it has taken two weeks of confusion and mismanagement for the rules to be confirmed by a second hearing by the Federal Court.

In the end, to ensure that Djokovic was forced to leave Australia, the Minister for Immigration had to resort to one of the most draconian powers available to a minister in any western democracy – a law introduced to give the government absolute power over asylum seekers to prevent them ever settling in Australia on the basis that they could pose a threat to the country.

The Federal Court on Sunday confirmed that the government had the power to eject Djokovic because his refusal to receive a Covid vaccination might inspire anti-vax forces in Australia to intensify their anti-vax campaigns.

This was despite the fact that the anti-vax movement includes MPs from the Morrison government who are some of the country’s most out-spoken anti-vax advocates – leading to accusations of rank political hypocrisy.

While legal experts said the ruling meant that the Minister had virtual “God-like” powers and could ultimately be used to suppress legitimate political expression, the government welcomed the decision as reaffirming Australia’s tough border regime.

While this meant the end of the road for Djokovic, he at least was able to check out of the Park Hotel and leave the country.

As Djokovic flies out of Australia – possibly never to return – the streets around the Park Hotel were vacated by the media pack as the story moved on

Djokovic seems to have been unmoved by his fellow detainees’ pleas to help use the misfortune of his stay in detention to advocate for them. Djokovic has said nothing about the inmates at the Park Hotel.

Instead, the message for them from the Djokovic affair is that the government’s powers to continue detaining them indefinitely remain absolute.

Whether the ejection from Australia of the unpopular world number one tennis player and the reaffirmation of Australia’s tough borders has any political spin-off for the government remains to be seen.

Morrison’s problem now is that attention will swing back to the government’s “let it rip” change to its previously hard-line anti-Covid measures. With an increasing number of Australians sick and dying, the odds are that the Novak Djokovic affair will simply be a footnote to the story of the coming Australian election campaign – as will the plight of the Park Hotel political prisoners.

Headline image credit: Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

Used under the terms and conditions of Creative Commons license