Here is a chart that reveals a UK economy in the doldrums and shows where it could be heading. John Egan decribes the challenges this presents to raising the nation’s prosperity and social cohesion.

Since the global financial crisis (GFC) hit in 2007, the United Kingdom economy has more-or-less flatlined. Last week the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) produced a veritable avalanche of data to explain why.

Embedded deep within the UK economy is a long-recognised productivity puzzle. While its causes and effects may be debated, the underlying picture is clear – and its resolution will be fundamental to the outcome of political projects for decades.

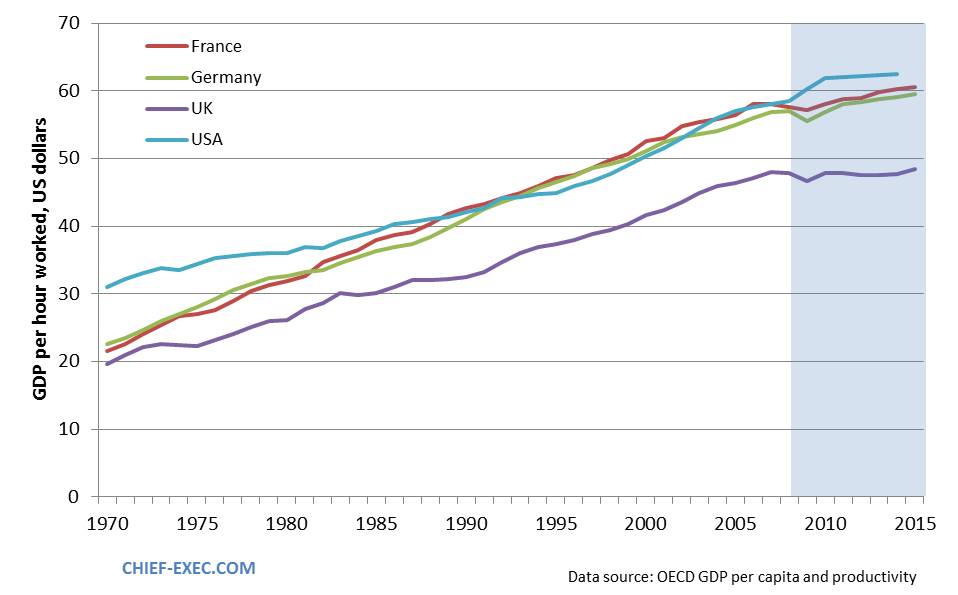

For 40 years there had been routine productivity growth as seen in the value added per hour of labour, which had been the essential source of increasing prosperity for the workforce. Since the GFC this economic escalator has broken down. As a result, productivity in the UK has fallen further behind comparable advanced economies and its population has become relatively less well-off.

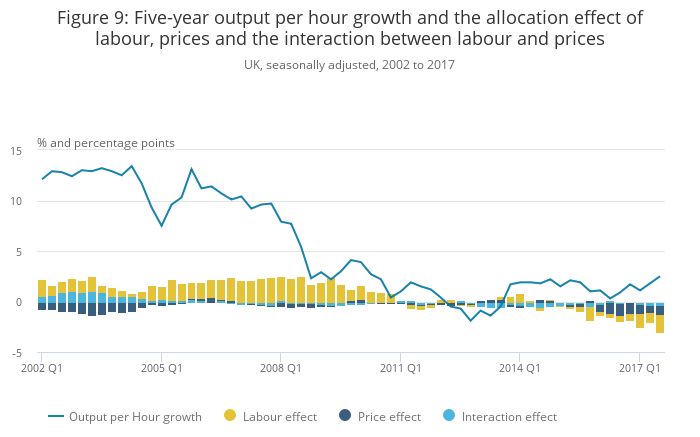

The conventional response to low productivity appears in the Industrial Strategy of UK chancellor Philip Hammond, which is designed to stimulate investment and innovation in industry, so that the British worker may make better products, quicker and with less waste. Using this “within industry” effect, Mr Hammond wants to push up the blue line in the ONS headline graphic towards five-year growth levels of about 12 per cent that appeared normal for the UK economy before the GFC.

The smaller bars on the same ONS graphic reveal some additional “allocation” factors that before 2008 were relatively small and secondary. These account for workers who chose to change jobs to work for a more productive company and, by doing so, increased their own productivity with a reasonable expectation of a higher wage. Price rises of the goods they produced also increased their added value.

What is clear from this headline graphic is that, nowadays, these allocation effects are no longer small and secondary. They are significant and have become negative. That is, workers are moving towards less productive industries. Indeed, this “shifting composition” of the UK economy accounts for about two-thirds of the decline of UK productivity growth since the financial crisis.

Senior ONS economist Richard Heys says: “It is becoming increasingly clear that a shift from people working in highly productive industries, such as mining, to less productive industries, such as food and beverage services, is contributing to the UK’s overall weak productivity performance”.

It is a trend that could compromise Government policies to enhance “within industry” productivity. If it were to continue it would mark the point where the historically advancing UK economy became stuck in reverse gear.

It should cause some concern as it appears that the zombies might now be proliferating

With remarkable synchrony, the ONS analysis appeared in a week that saw a notable “correction” of company share values. Around the world stock markets suffered one of their worst weeks since the financial crisis. The spectre of rising interest rates, from their extremely low levels, had apparently spooked the market.

The evolution of the unusual productivity behaviour since the 2007 GFC charted by the ONS coincides with the period of very low interest rates and a plentiful supply of capital issued by national banks. An explanation to link the two phenomena is provided by an extensive industry level study conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Multiprod Project.

This OECD analysis highlights the appearance of “zombie companies” that can exist in a low interest rate economy and which essentially trap their employees in low productivity environments. Diminished labour mobility is clearly visible in the ONS headline graphic after the GFC, reflecting the desire of workers with an uncertain outlook to stick with the jobs they have.

It should cause some concern as it appears that the zombies might now be proliferating.

Will rising interest rates provide the cure? That is at least part of the thinking behind the recent falls in company share values. Nobody wants to be left holding the stock of the zombies with their potentially unsustainable balance sheets – wherever they are.

It appears that the interest rate induced correction of the market will inevitably produce its own series of seismic events. There will be a new set of winners and losers – and social repercussions.

The decade of very low interest rates, that seems to be coming to an end, has resulted in increased inequalities as those with access to cheap capital have been able to benefit from a substantial growth in the value of their properties and stocks. The Federal Reserve in the US has recently reported that the top 10 per cent of America’s most wealthy own 77.1 per cent of that nation’s wealth. For the UK this figure is around 45 per cent.

If policies and interest rates bring UK society back to resemble the pre-GFC picture, how will those worker’s respond to the need for extra value creation to reimburse the increasing interest for the capital holders? How will the young, on entering the labour market, seek to acquire the standards of living that were accessible to their parents? How will the better-off old seek to manage their capital gains in a future where access to healthcare may become increasingly scarce and therefore expensive?

Allocation effects and low interest rates make interesting statistics. Unravelling their interaction will be challenging and could have unexpected political and social consequences.

In the same series:

Second article: Chief-Exec series: The iceberg of intangible capital