Now the Australian Coalition Government must decide if it will protect the high-skill high-wage jobs in advance manufacturing that it generated, writes shadow Industry Minister Kim Carr.

When General Motor’s Australian subsidiary, Holden, shut down its assembly plant last month, Australia’s 100-year-old tradition of producing passenger cars came to a halt.

The other automotive manufacturer with an Australian production facility, Toyota, had ceased operations several weeks earlier.

The closures provoked a spate of commentary, locally and around the world, much of it intended to demonstrate that the decisions made by Holden and Toyota were inevitable.

Typical among these was the verdict of Peter Campbell and Jamie Smyth, in London’s Financial Times.

The events in Australia, they argued, were a warning to auto manufacturers in developed nations that they will increasingly lose out to competitors in low-wage countries.

It is the kind of analysis that appeals to those whose predilection for neoliberal economics makes them prefer one-size-fits-all explanations. But it ignores what actually happened in Australia.

Every country with an automotive industry assists it in some way, because the industry is a source of hi-tech, advanced manufacturing capabilities that flow over into the wider economy

The striking thing about the end of car making in Australia was its gratuitous nature. It did not have to happen.

Both companies wanted to continue production. Holden had plans for A$1 billion in new investment to develop two new models, and Toyota’s Australian subsidiary was a profitable business with a thriving export market.

The closures were not a matter of economic necessity, they were politically orchestrated.

The car makers chose to leave Australia because Australia’s conservative Coalition government goaded them to leave.

Every country with an automotive industry assists it in some way, because the industry is a source of hi-tech, advanced manufacturing capabilities that flow over into the wider economy.

In Australia that assistance was modest by global standards.

On a per capita basis, Australian taxpayers contributed A$17.40 (£10.02) a year to the industry, about what they would pay for a football or movie ticket.

The level of public assistance to the automotive industries in other high-wage countries, such as the US, the UK, Germany and Sweden, is much greater.

And, with differences of emphasis, it is generally accepted across the political mainstream in those countries.

But in Australia the Coalition Liberal and National parties made clear even before they took office in 2013 that they wanted a hefty cut in assistance to automotive manufacturing.

At least, that is the way they explained their aims in opposition. In government, the Coalition did indeed make cuts, but it became apparent that their real agenda went further.

Ideologues in the new government wanted to withdraw support for the industry altogether.

Their vision of Australia’s future was of a commodity exporter seeking favourable trade agreements for its minerals and agricultural products.

Manufacturing and the automotive industry in particular, did not fit into that narrow frame.

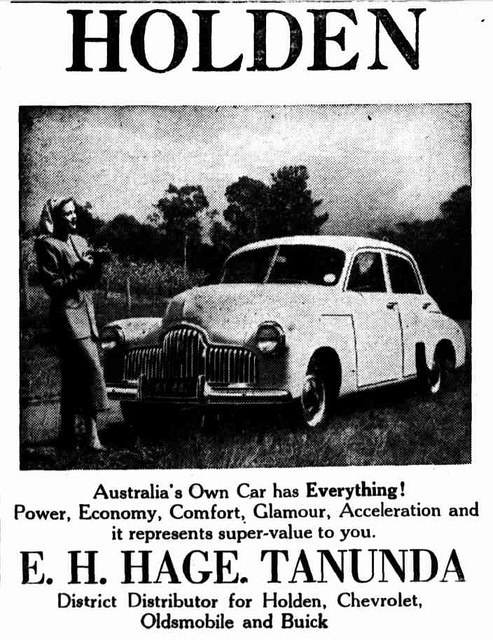

Holden Ad from 1949

Holden became the immediate target, because the company was in negotiations with the government for an increase in assistance to offset the competitive disadvantage caused by the then very high Australian dollar.

Within weeks of the 2013 election, the then Treasurer, Joe Hockey, announced: “We are not running down the street chasing an individual car maker with a blank cheque made out by the Australian taxpayer”.

Shortly after, the Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, insisted: “There’s not going to be any extra money over and above the generous support the taxpayers have been giving the motor industry for a long time”.

Then Hockey and the Deputy Prime Minister, Warren Truss, used Question Time in Parliament to launch a blistering attack on Holden.

Hockey said it was time for the company “to come clean” with the Australian people: “Either you’re here or you’re not”.

Truss, who was acting Prime Minister at the time, said: “… Today I have written to the general manager of Holden, Mr [Mike] Devereux, asking General Motors, to make an immediate statement clarifying their intentions in this country”.

The real message was not a request for clarification. It was an implied threat, and General Motors understood it as such.

The company’s management in Detroit instructed Devereux to announce the end of production, setting in motion the sequence of events that reached its dismal conclusion last month.

Once Holden announced it was going, Toyota was left with no choice but to follow suit.

Without at least two motor vehicle producers, there would not be enough demand for component makers in the supply chain to sustain the industry.

The dire consequence projected by economic modellers at the University of Adelaide – a two per cent cut to Australia’s GDP – may not come to pass.

But there will be social and economic disruption. Thousands of jobs will be at risk as the effect of the closures ripples across the economy.

The welfare bill alone will cost Australian taxpayers far more than it would have cost them to continue assistance to the industry.

And all this has happened because of political chicanery.

It did not happen because auto workers in Thailand earn less than auto workers in Australia.

Nor did it happen because the lowering of tariff barriers has given Australia the most fragmented and highly competitive motor vehicle market in the world. Those things did not make life easy for Australia’s car makers. But they did not make the production of passenger cars unsustainable. The attitude of the Australian government did that.

In no other developed nation has a government demonstrated so little understanding of what an automotive industry contributes to the national economy.

And in no other developed nation has a government exhibited such a combination of malice and incompetence in dealing with the industry.

Contrast the attitude of the Australian government to its automotive industry with that of another conservative leader, UK Prime Minister Theresa May.

Last week she chaired a meeting of the executives from the UK and European automotive sectors, at which they discussed the challenges and priorities for the industry.

They talked about the global transition to low-emission vehicles, and developments in manufacturing technologies, including the internet of things.

Mrs May spoke of the success of the UK’s automotive industry, which is now the third-largest in Europe.

Only a few decades ago, at the end of the Thatcher era, some people had predicted the demise of British automotive manufacturing with the same glee that neoliberal commentators have hailed the end of car making in Australia.

But it did not happen in the UK, because both sides of British politics recognised the importance of the industry in the wider economy and accepted the need to support it.

The same political challenge now confronts Australia.

Thousands of jobs will be at risk as the effect of the closures ripples across the economy. The welfare bill alone will cost Australian taxpayers far more than it would have cost them to continue assistance to the industry

In the increasingly competitive global automotive market described in Campbell and Smyth’s Financial Times report, the advantage will not automatically go to manufacturers who pay the lowest wages.

The advantage will go to manufacturers who have the design skills and technological capabilities to identify and satisfy the market’s changing demands.

Australia’s automotive industry has those skills and capabilities, which is why the former motor vehicle producers are retaining design, engineering and test facilities in the country.

Production of passenger cars has ceased, but Australia’s automotive industry is not dead. It still has the potential to remain at the cutting edge of global advances in technology and product design, including electrification, light-weighting, gaseous fuels and telematics.

The choices that Australian governments make now will determine whether those capabilities are retained.

Those choices will not only be about the kind of economy and the kinds of manufacturing Australia engages in. They will be choices about the kind of society Australia wants to be.

Australians have always been proud of their country’s strong democratic and egalitarian traditions.

Those traditions have been sustained by economic opportunity – by the provision of high-wage, high-skill jobs.

Only a strong advanced manufacturing sector will provide those jobs, and the way to build that strength is to consolidate and enhance the skills and capabilities of the automotive industry.

Senator Kim Carr was Industry Minister in the former Australian Labor government. He is now Shadow Minister for Innovation, Industry, Science and Research.