The UK should beware when it looks to Australia for a solution to ‘stop the boats’. The cost to the Australian taxpayer of detaining asylum seekers has been estimated at A$4 million per detainee, writes Geoff Kitney.

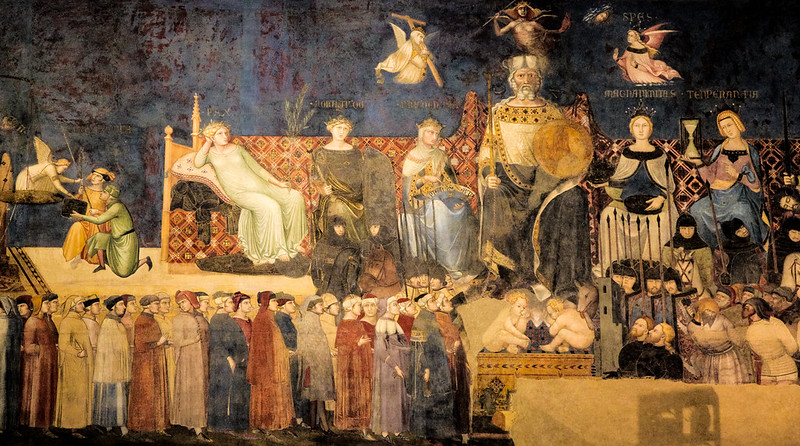

In the Town Hall, just off Palazzo Pubblico, in the fabulous Medieval Tuscan city of Siena, hangs a famous mural titled “The Allegory of Good and Bad Government”.

Fourteenth Century Renaissance artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s painting juxtaposes corrupt, religious government with good, democratic government and invokes all who see it to choose the latter over the former.

But there is a footnote to this exhibition with deeper significance. Also hanging in the room is a figure of an angel bearing the name “Securitas”. It signifies that the key to prosperity under a good and just government is security, that people are freest when they have democracy and live in safety. (See Footnote).

What was true in 14th century Tuscany is equally true today.

The best governments are those which give their populations the ability to live their lives in liberty and without fear.

The problem with this is that there is often a tension between the two.

Fear is a powerful emotion not always rationally felt. Often it is hard to identify what is real and not real when it comes to threats to security, it is easy for people to be tempted to see threats where they don’t exist.

Which makes it easy for less scrupulous governments to make people frightened and to then assure them that only their government can protect them from that perceived threat. It’s a political strategy with a long history of success.

In today’s world where small bands of extremists have the means to infiltrate borders and inflict murder and mayhem on the people inside them, fear is everywhere even where the threat is minimal or non-existent.

This has given the issue of border protection powerful political potency.

Politicians promising to secure the borders of their countries have made political capital out of the issue since the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States.

The “Take Back Control” slogan which was used to promote the case for Brexit played successfully on the idea that Britain would be more secure outside the European Union, behind its own borders.

Twenty years ago, the slogan “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come” was used to powerful effect by the then Australian Prime Minister, John Howard. His conservative government sent SAS troops to prevent a ship carrying more than 400 asylum seekers, rescued from a sinking people smugglers’ boat, from entering Australian waters.

It is hard to identify what is real and not real when it comes to threats to security, it is easy for people to be tempted to see threats where they don’t exist.

Australia has had refugee boat arrivals – crossing the dangerous stretch of ocean between Indonesia and North-West Australia – since the Vietnam war ended in 1975.

But as numbers grew, and it became clear that people smugglers had turned the desperation of refugees into a lucrative trade, public attitudes towards refugees hardened. In late 2001 a heavily overloaded rickety boat trying to reach Australia in rough weather founded and 353 asylum seekers drowned – but this invoked little apparent public sympathy.

Instead, the Howard government – in the immediate aftermath of the September 11 terror attacks on the US and in response to fears that terrorists might enter Australia disguised as refugees – promised never to allow any “illegal immigrants” to be permitted to settle in Australia. It rode a wave of popular support for its hardline border policies to comfortably win re-election.

Howard’s then press secretary, Tony Abbott, subsequently rose through conservative political ranks to himself become prime minister in 2013 – just as the issue of border protection had been revived with a dramatic increase in asylum boat arrivals following a relaxation of border protection measures introduced by the then centre-left Labor government.

Abbott won a landslide victory after promising that he would “stop the boats”. One of his first steps as prime minister was to establish what he called “Operation Sovereign Borders”.

In secret operations, Australian navy vessels began intercepting boats and turning them back to Indonesia. Where boats were unseaworthy, the Navy provided lifeboats for the return journey.

Asylum seekers who had arrived in Australian waters as a result of Labor’s softened border laws were subject to mandatory detention and transferred to two detention camps set up – at Australia’s expense – in neighbouring Papua New Guinea and the small Pacific Island of Nauru. They were to be held until they either chose to return to where they came from or were accepted as refugees by third countries.

Nearly 2,500 asylum seekers were put into offshore detention.

Eight years later nearly 10 per cent of those asylum seekers are still in those camps.

‘The prospect of sending asylum seekers ‘offshore’ might sound like a convenient solution in theory. But the reality of this policy has proven it to be difficult, ineffective, expensive, cruel and controversial.’

Madeline Gleeson, a lawyer and senior research fellow at the Kaldor Centre

Despite international condemnation, the Australian public has continued to support this policy and shown scant sympathy for those who have been detained in harsh, prison-like conditions.

The conservative parties, which have governed Australia since 2013, have claimed the policy a success: Australia’s borders had been secured, the Australia people protected, the people smuggling industry had been destroyed and countless lives which otherwise could have been lost at sea had been saved.

For those who had been victims of this policy and languished in Australia’s offshore detention centres as effective prisoners, the policy has remained uncompromisingly harsh.

There is an important connection between what happened in Australia in 2013 and what is now happening in the United Kingdom.

Tony Abbott, who lost the prime ministership after an internal putsch over his domestic policies, became an informal adviser to UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Abbott, who was born in the UK and emigrated to Australia as a child, is a committed Anglophile with strong connections to senior UK Conservatives.

Johnson had appointed Abbott as an advisor on trade policy and, behind the scenes, Abbott actively lobbied Johnson and his ministers – particularly hard-line Home Secretary Priti Patel – to adopt Australia’s uncompromising approach to border protection.

Abbott appears to have had success.

Following the recent surge in arrival of asylum seekers crossing the English Channel, the Johnson government decided to act to deter “illegal entry” into the UK with its Nationality and Borders Bill. The bill, which has just passed the House of Commons, includes a raft of laws intended to seal the UK’s borders and allows for offshore detention in third countries.

There has been an angry response to what has been called “racist” legislation.

Strong objections have been raised by a wide range of groups, from concerned Tory MPs through to refugee action groups and human right organisations.

The dissenters are being urged on by people familiar with the Australian experience on offshore detention – including former detainees – to fight to stop offshore detention by the UK.

The Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, based in Sydney – a strong critic of the Australian laws – has rung alarm bells about the UK legislation.

Madeline Gleeson, a lawyer and senior research fellow at the centre, warned in an article for the on-line publication The Conversation that there appeared to be a view in the UK government that Australia’s offshore detention and processing of refugees had been successful. Nothing could be further from the truth, she said.

In fact, it had been an unmitigated disaster.

The cost had been astronomical – estimated at A$4 million per detainee.

The dehumanising effect on those held in detention was devastating (including suicides of inmates).

There was also little evidence to show that it had had a deterrent effect. The fact that asylum seeker arrivals on Australian shores had apparently ceased in recent years (although no-one knows for sure because the government’s “on water” border protection activities are shrouded in secrecy) was primarily due to the turning back of boats.

“The prospect of sending asylum seekers ‘offshore’ might sound like a convenient solution in theory. But the reality of this policy has proven it to be difficult, ineffective, expensive, cruel and controversial,” Ms Gleeson wrote.

However, in Australia, there is not the slightest sign of the conservative government relenting on its offshore detention policy. Those still in detention can only hope for it to end if they are accepted as migrants in third countries.

Whether it is true or not – and regardless of the motive for the policy (racial prejudice or national security) – Australians continue to see harsh treatment of refugees as necessary to ensure the nation’s sovereign borders remain protected from unwanted intruders.

Footnote: The symbolism of the art work in Siena’s Town Hall is described in Dov Alfon’s book A Long Night in Paris (MacLehose Press). Alfon is a former Israeli intelligence officer and editor-in-chief of the influential newspaper Hareetz. He is now editor of French daily Liberation.

Headline image credit: Janossy Gergely/Shutterstock.com

In-story image: The Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government Credit: Erik Törner

Used under the terms and conditions of Creative Commons license