The recent uprising of the Gilets Jaunes in France is one idiosyncratic national reaction to a global problem. But global problems demand global answers and Maxwell’s demon offers a possible solution, writes John Egan in Paris.

This week the Joseph Rountree Foundation reported that the number of workers in poverty in the United Kingdom has hit 4 million. Nearly all are working parents finding it harder to earn enough money to pay for food, clothing and accommodation – to deal with the rising cost of living.

In France, a similar struggle to make it to the end of the month by those now known as the Gilets Jaunes will continue despite this week’s announcement to defer the fuel tax rises that sparked their national uprising. They are now sure to organise and continue to exercise their discovered potency.

Even before the global financial crisis (GFC) “elephant charts” were pointing to economic victims of the globalisation of commerce – a large block of lower-middle class and semi-skilled workers in developed nations. The austerity that followed the GFC made matters worse.

People of different nations have responded in a variety of ways. The discontent and its perceived relationship to immigration saw many in the UK turn to the Brexit solution. In the United States, President Donald Trump offered a promise to make “America Great Again”. Italy has elected an anti-establishment Government and, across Europe, “populist” political parties are in the ascendency. Even President Macron’s election in France 18-months ago bore the hallmarks of an expression of discontent with the status-quo.

One could look further, to the enormous flows of economic migrants from under-developed economies. These have only added to a sense of global disorder. And responding to the global challenge of climate change could in many people’s eyes see a further loss of prosperity either through higher energy costs or catastrophe.

Whether it is Brexit, trade tariffs or yellow jackets, these local reactions are products of ideology, arising from nationalism, liberal and illiberal democracy or social solidarity, depending on a nation’s temperament.

But global problems, one might expect, demand global solutions and at the very origin of the problem, and therefore the solution, is the consumer. There is a need to deepen our understanding of homo oeconomicus – for which we can employ the imaginary demon conceived by the great Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell 150 years ago.

Precisely as Chief-Exec.com recently described in the case of Maxwell’s Entrepreneur, Maxwell’s Consumer lives in a world of commodities to which he or she can attribute a value. This perception of value is adopted here as a form of energy [1] which enables consumption to be seen as part of a physical system.

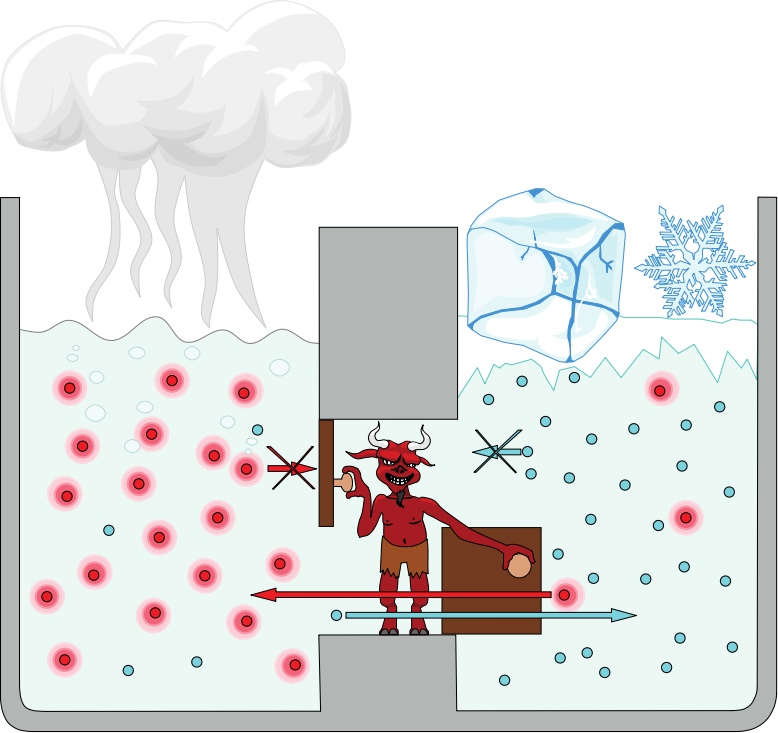

Within a large world packed with commodities is a much smaller and private place – the household of the consumer. Maxwell’s original demon could operate a shutter through which to select and allow fast moving “hot” gas molecules to enter the household, leaving the slower moving “cold” molecules outside. It would be a way to heat your house – but you would still need to pay the bill [2] (see graphic below).

Maxwell’s Consumer operates a similar shutter to allow commodities to enter the household whenever their perceived value is greater than a price allocated for their purchase. Once selected the entire value of the goods enters the household, for the cost in money paid for their acquisition.

Importantly, the commodity environment inside the household then differs from that outside. It gains a higher capacity for value creation due to a concentration of acquired value – as perceived by the consumer [3]. This difference gives the household an “edge” as already explained in a more conventional sense for the entrepreneur. It remains an automatic consequence of competition that money flows towards points of greater value creation.

Having consumed through their shutters their valued commodities, this acquired value then drives the productive activities of each household. Elsewhere in Chief-Exec.com we have described these activities as being part-artist, part-photocopier – the artist being the personality that creates new information (innovation), the photocopier being the one who replicates information that has already been created (production).

Household commodities include food, heat and shelter to sustain those who live within its reassuring boundaries. Capital items for transport and communications, for example, enable these in-dwellers to be more productive [4]. Within each household the cultural capital and social capital described by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu should not be ignored [5].

The consumer has a productive “edge” because of the value of the commodities consumed AND the effectiveness of the acquired economic, cultural and social capital. If the household simply replicates the external commodity-filled environment there would be no edge. In the classical world of the labour theory of value, there would be no deer and beaver hunters but perhaps only the former, and we would all be eating venison.

It is the differential nature of the economic environment inside and outside the household that enables the inhabitants to have fulfilling and sustainable lives – to some degree. Their bipolar personalities as artists and photocopiers variably combine, in the creation and copying of information, for their own satisfaction and in the practice of their employment. The latter is, of course, important for earning the income for the next round of acquisition, so that making it to the end of the month is assured.

And, based on this assumed physical system of consumption and production, we might conclude that:

- Inequality is not only an inevitable economic outcome, but essential for the consumption-production machine to operate.

- Consumers should resist pressures to conform and welcome the individuality of their preferences, as this is the source of their capacity to live fulfilled and sustainable lives.

- The failure of any member of the homo oeconomicus family to make it to the end of the month is everywhere a form of injury that is preventable by appropriate societal redistribution of income directly and through in-kind contributions for education and health, upon which future wellbeing depends.

- The concept of a basic universal income has merit as a social investment to ensure the smooth running of the consumption-production machine.

- If running the photocopier forever faster leads to a kind of madness, then it is time to favour the role of the artist and enable innovation to trace a path to a sustainable future.

Notes

[1] The bioenergetic origins of the energy of consumer perceived value are considered elsewhere on Chief-Exec.com.

[2] The bill is paid for in the expense of deleting information, as explained in Maxwell’s Entrepreneur.

[3] The consumer may discount commodities that are beyond their capacity to purchase either because of their price or availability.

[4] We interpret capital-enhanced productivity as being the cycle time for the creation of value, the transfer of this value to a consumer and the reimbursement back to the producer resulting from a transaction. See: ‘Consumptivity’: the heartbeat of a modern economy.

[5] In his book “Raisons Pratiques” (Practical Reason), Pierre Bourdieu uses Maxwell’s Demon as a metaphor to explain the acquisition of cultural capital where, for example, the demon controls an individual’s access to higher education.

Headline Photo Credit: Natali_ Mis/Shutterstock.com

Maxwell Demon graphic: Sergey Merkulov/Shutterstock.com