Times are a changing for education, health, employment and income. John Egan reports on the findings of the OECD on emerging inequalities.

For a young man born at the turn of the 21st century who is now pondering entering higher education and preparing to take on the debt needed to fund his passage, he might take some consolation from the fact that he can reasonably expect to live almost eight years longer than his less well-educated peers.

Findings that levels of education are linked to overall income and longevity as reported in Preventing Ageing Unequally, published this week by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), may not raise many eyebrows. However, the report goes on to reveal a more challenging view of the world the young man will inherit.

Across the 35 OECD member countries – including most developed economies – in 2015 about 28 per cent of the population was aged 65 years or older. By 2050, when our prospective student will become a 50-something, it will, on average, be 53 per cent. However, his future will be dramatically different depending on the country in which he chooses to live.

People will live longer but more will have been unemployed at some point in their working lives and earned low wages, while others will have enjoyed a life with higher, stable earnings.

By 2050, in Japan and Spain, more than 75 per cent of their populations will be older than 64, in Germany it is predicted to be almost 64 per cent, while in the UK it should be about 46 per cent. Meanwhile, in the developing and highly populous India and Indonesia, the proportion of people aged 65 and over will be about 23 per cent.

Government policies and circumstance will determine how the education, health, employment and income of our young male student will combine and lead to what person he will become when he is 50. The report advises on the former by understanding the complex interactions between those four crucial factors with age.

For example, low-educated people have a higher risk of disability, a risk which narrows at older ages. And at all ages, men and women in bad health work less and earn less when they work.

If our student has the misfortune to become afflicted by bad health, over his whole career this would typically reduce lifetime earnings by 17 per cent. For his peers with a lower level of education this loss would be almost double at 33 per cent.

By extrapolating trends from today, the OECD report predicts a life journey through a world of growing inequality. Inequalities start building up from early ages. “Disadvantages in health, education, employment and earnings reinforce each other and compound over the life course,” the report says.

The future elderly will be in more diverse situations: people will live longer but more will have been unemployed at some point in their working lives and earned low wages, while others will have enjoyed a life with higher, stable earnings.

“In most countries, people’s average real incomes are still higher than those of previous generations at the same age. But this is not the case any more for those born from the 1960s compared to the generations born one decade earlier.

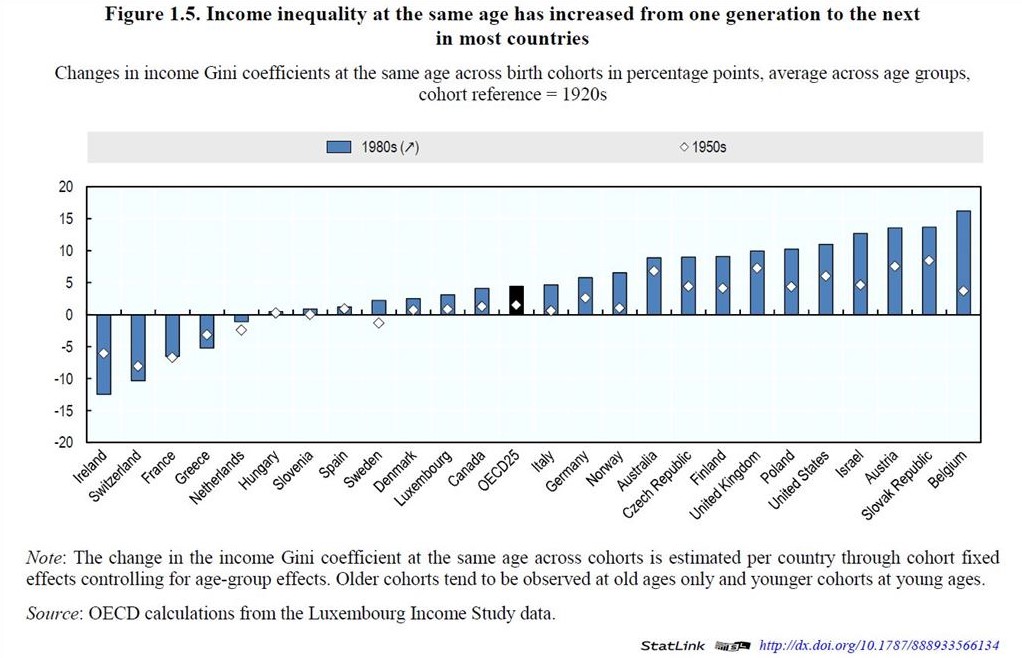

“Income inequality has been rising from one generation to the next at the same age in two-thirds of the countries, in particular among younger groups for which inequality is nowadays much higher than for the elderly.”

The above chart is based on the Gini co-efficient which is commonly used to measure income and wealth inequality. In the majority of countries on the right of the chart inequality has increased particularly for younger generations, while in the five countries on the left inequality has fallen.

Chief-Exec.com has reported on the French economist, Thomas Piketty’s findings, that wealth inequalities are also increasing.

Preventing Ageing Unequally asserts that, “ageing unequally is detrimental to future economic growth, particularly where inequality of opportunity locks in privilege or exclusion, undermining intergenerational social mobility and jeopardising social cohesion”.

Our young student faces a future in which he will not experience higher incomes and lower poverty risks, as was the case for earlier generations. He should expect to live longer but will be likely to face higher inequality in old age with large disparities in health status among his ageing neighbours.

|

To tackle the issues of ageing unequally, the OECD recommends that countries should take a life course approach focusing on three areas: Prevent inequality before it accumulates over time. Measures should include providing good quality childcare and early education, helping disadvantaged youth into work and expanding health spending on prevention to target at risk groups.

Mitigate entrenched inequalities. Health services should move to a more patient-centred approach and employment services should boost efforts to help the unemployed back into work, as well as remove barriers to retain and hire older workers. Cope with inequalities at older ages. Reforms to retirement income systems cannot remove inequality among older people but can mitigate it. Well-designed first-tier pensions can limit the impact on pension benefits of socio-economic differences in life expectancy. Some countries have pension adequacy risks, especially for women. Making home care affordable and providing better support to informal carers would also help reduce inequalities in long-term care.

Further information, including the report and country notes, is available here |

Headline Photo Credit: Pavel Ilyukhin/Shutterstock.com