For better or worse, further variants must be anticipated, writes John Egan.

Governments around the world will be holding their breath.

Many have taken a big bet that the latest coronavirus variant sweeping the world will disappear as quickly as it arrived. They hope that hospital capacity will be protected by vaccination campaigns – particularly the third “booster” jabs to re-sensitise national immunity.

The hope that the Omicron variant is more benign than its predecessors is supported by data showing relatively low numbers of people have died compared to earlier waves of the pandemic.

However, Omicron was only identified at the end of November in South Africa and it was declared a Variant of Concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 26 November 2021. This concern was raised due to the high number of mutations – 50 – that define Omicron, including 32 on the important spike protein that unlocks its mechanism to infect.

The subsequent experience of South Africa supports the assumption that the epidemic waves due to Omicron may be short-lived and relatively less lethal than earlier variants. In our analysis on @CovidAnalytics we can see that Covid-19 cases in South Africa have recently fallen and our indicators for the epidemic in the country have returned to normal after a tumultuous few weeks.

Many other countries remain in the exponential growth phase of the Omicron variant, with huge rises in the number of their Covid-19 cases. Japan provides one particularly striking example of this.

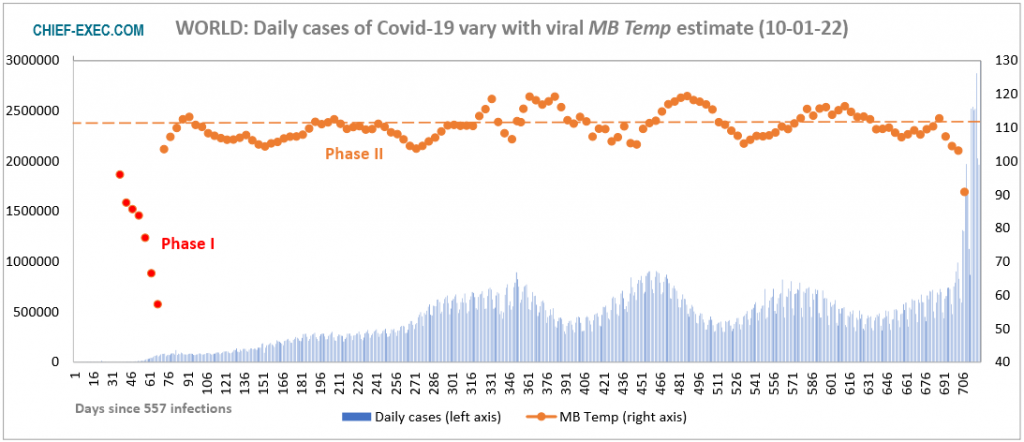

A sobering picture comes from the analysis of global infection numbers, obtained from the Our World in Data database. It is a level where one might imagine the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus as a single organism that is infecting the planet.

Previously, for 700 days, SARS-CoV-2 existed on a global scale quite unperturbed by the myriads of national lockdowns, social separations and vaccinations. It has been a machine ticking through five cycles of rising and falling waves of infection – as regular as clockwork.

With the arrival of the Omicron variant everything has changed. There has been a meteoric rise of Covid-19 infections on a global scale. Our MB Temp indicator, based on a thermodynamic modelling of the pandemic, has fallen to levels only seen at its start. The viral infection-propagation cycle of this simulation – the engine of the epidemic – has had to spin about 20 times faster just to model the latest infection data.

The Omicron variant has only existed on a global scale for less than two months. While preliminary observations of its relatively benign impact have been encouraging, such is the difference between this variant and its predecessors, that its longer-term impacts cannot be accurately anticipated based on what has gone before.

The deployment of the precautionary principle is therefore appropriate. A gung-ho rush back to a way of life that existed pre-2019 would be premature until we know more.

Further variants must be anticipated – for better or worse. And some of the signs do give reason to hope for the former.

Living with the coronavirus is going to mean adapting to it – not ignoring it as much as possible, and getting on with life. It will probably be around for a number of years – we cannot say how long – but the sooner we understand that we will need to adapt, the better placed we will be to deal with the future as and when it arrives.

For related articles on Chief-Exec.com : Click Here