It takes courage to revisit political mistakes but it’s easier for leaders to turn a blind eye, writes Geoff Kitney.

If there was a moment that summed up the weird politics of Britain’s Brexit saga it was surely when Rishi Sunak invited David Cameron to take up the post of foreign secretary in his government.

Even more surreal than the appointment was the quiet acceptance by much of the media, and the wider public, of said appointment as part of the new normality of British political life in post-Brexit Britain.

As an outsider who once lived in the UK and followed the Brexit story closely, it seemed that so much had become weird in British politics since the then prime minister David Cameron set Britain on the path to leaving the European Union in 2016. Bringing Cameron back from the political dead summed up what had happened to a country in which strangeness had become the new norm.

It also seemed to sit comfortably with the contemporary political mood in Britain where the Brexit referendum is now deemed ancient political history and should not be revisited.

David Cameron’s folly was to try to defuse a divisive debate in the party he led. Instead, Conservative Party bickering on Britain’s place in Europe and the referendum that followed led to one of the greatest own goals in political history. But so much has changed since the Brexit vote as Cameron’s successors have mismanaged the UK’s post-Brexit affairs, leading the Tories into ever deeper political trouble. Recalling Cameron did not seem so crazy, particularly because of his deep experience and his undoubted political skills. Rishi Sunak obviously concluded that even a damaged Cameron was his best option for Foreign Secretary..

Nearly eight years after the Brexit referendum – and despite the fact that there is no foreseeable prospect that Britain will arrive at the sunlit uplands of independence and opportunity promised by Brexiters – there seems to be a deep resistance to revisiting the Brexit debate.

It appears likely that Brexit will be well down the list of issues to decide the result of the forthcoming UK general election. The Labour party has no wish to elevate it. All that is on offer is to “make Brexit work”. Labour has shut out the question of whether it is actually possible for Brexit to ever work.

Britain would be far better off as part of a great trading bloc, inside the EU single market

At the slightest suggestion that it will change its mind after the election, the Labour Party dismisses the idea immediately.

In the past weeks Labour has moved quickly to deny that it planned to have the UK rejoin the EU customs union. This followed a brief for clients by the political consultancy, Eurasia Group, citing unnamed insiders saying Labour would revive the idea of a “high alignment” trade border deal with the EU.

This would return the UK to the EU customs union and give it the advantages of EU free trade agreements with countries with which it has failed to secure such agreements.

This would require the UK to pull out of a free trade agreement it has signed with Australia and its membership of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Returning to the EU customs union would overcome one of the greatest failings of Brexit so far – Britain’s lack of success at securing free trade deals with major trading partners. It was a cornerstone of the Brexit promise – that, free of the EU, the UK could once again become the great trading nation it was in the pre-EU membership days.

Comments on the Eurasia Group article were overwhelmingly supportive of the idea of rejoining the EU customs union. However, critics said it would not happen because Labour was “terrified of Red Wall voters” who backed Brexit (and Boris Johnson) but whose votes Labour needs to win back traditional Labour seats.

Seen from the other side of the world – and from one of the few countries with which the UK has been able to negotiate more than a token FTA – this is bizarre.

“Make Britain a great trading nation again” was one of the hollowest of the Brexit slogans.

It was a promise made by people who had not the slightest idea what it would take to achieve such a goal, given that Britain had virtually no knowledge or infrastructure for doing trade deals as a result of its decades-long membership of the European Union and the fact that trade policy was run from Brussels, not London.

When I was a correspondent based in London, I covered the World Trade Organization in Geneva and had good contacts with key trading nations. I never came across a Brit, except some working for the EU and who, as far as I remember, all remained working for the EU after Brexit.

The trade deals that Britain has completed since Brexit have been insignificant, to say the least. Australian trade negotiators – with long and deep experience of trade negotiations – took their British counterparts to the cleaners in the Australia-UK FTA deal.

British farmers, who voted strongly in favour of Brexit, are increasingly unhappy with the consequences for them of free trade agreements negotiated by the UK government, which they say have disadvantaged them.

Britain had virtually no knowledge or infrastructure for doing trade deals as a result of its decades-long membership of the European Union and the fact that trade policy was run from Brussels, not London

It would undoubtedly be In the UK’s national interest to abandon the fantasy of reviving the nostalgic dream of making Britain a “great trading nation” again and accepting the reality that Britain would be far better off as part of a great trading bloc, inside the EU single market.

The same could be said of the “take back control” slogan – arguably the Brexit inducement which most influenced voters – which offered the promise of tighter borders and limited immigration. The opposite has happened and the government, led by Rishi Sunak, has got itself into an unholy mess over asylum seeker boat arrivals. They were a tiny fraction of the “immigration problem” yet have been elevated to the level of a grave political crisis!

The Conservative government adopted the Australian slogan “stop the boats” as a simplistic catchcry for its policy, failing to recognise fundamental differences between the Australian situation and the British, including the sheer numbers seeking to cross the channel, the proximity of jumping off points. and the many more options for landing on the British coast compared to Australia.

The manifest failures of the Brexit project are also a stark reminder of the politics of “unintended consequences” which should have stopped David Cameron from gambling everything on a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU.

Australia has just been through a similar salutary experience.

Before he was elected Australian Prime Minister in May 2022, Labor’s Anthony Albanese promised that his government would give Australians the chance to right an historic wrong by voting in a referendum on a proposal to give constitutional recognition to indigenous people and to give them a formal “voice” in the affairs of the nation.

The plan appeared to have strong support but – at the end of a divisive, sometimes brutal and ugly campaign which brought to the surface racism and discrimination – the referendum was roundly defeated, delivering a heavy political blow to Albanese and setting back race relations and Aboriginal hopes for a stronger voice in the affairs of the nation.

Unlike Cameron, Albanese did not resign.

Some supporters of the proposition urged the Labour government not to give up on indigenous constitutional recognition, but Albanese said there would be no second chance in the foreseeable future.

The cost of this failure to Australian society has been heavy and the big issues associated with the plight of Aboriginal people remain unresolved.

Big political misjudgements have a heavy cost.

In Australia the plight of the indigenous population is undoubtedly worse now than before the referendum. The ugly political debate which preceded the vote brought to the surface the true depth of white Australian ignorance about Aboriginal disadvantage, lack of concern about it and the depth of racism towards Aboriginal people. Australia has been deeply divided by the referendum. Since the vote, however, the Labor government has left these issues hanging over the country, preferring now to talk about other subjects.

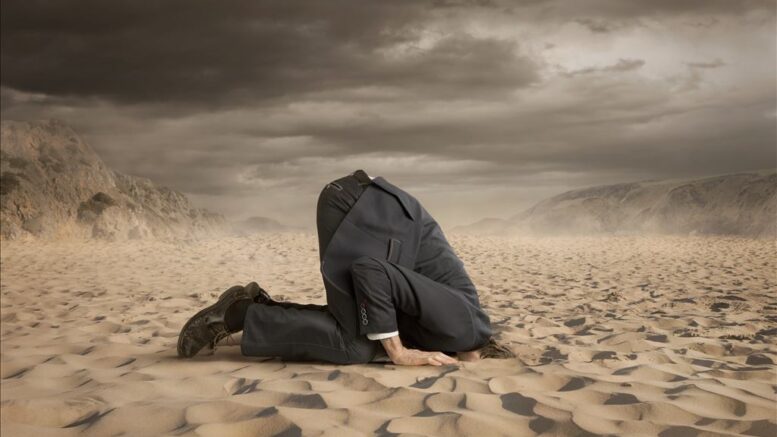

Seen from a distance, it appears that the mood in the UK towards the aftermath of the Brexit vote is similar. It seems that it is easier for political leaders to bury their heads in the sand than to face up to the true consequences of their miscalculations.

But to revisit and correct such mistakes involve huge risks. The leaders of the major political parties in both the UK and Australia have no intention of taking those risks.

Headline image credit: rangizzz/Shutterstock.com