Throughout Europe governments are reluctantly tightening restrictions that limit the freedom of their citizens. What can they learn from their Antipodean cousins?

Europe has already seen 5.6 million cases of Covid-19 which have led to 228,689 deaths. A first wave of the coronavirus pandemic in the spring then made Europe the epicentre of the virus. The persistent complications of Long Covid are just being recognised and their chronic consequences are not understood.

The relative calm of summer left space for economic and social activities of normal life to be restored somewhat. Those days are now over as a second wave of the pandemic is approaching at an alarming rate. It is difficult to estimate the force with which this will strike the continent and what measures will be needed to regain control of the epidemic.

In the southern hemisphere, as Australia and New Zealand move toward their spring, they themselves are emerging from a second wave of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus pandemic. Clues as to what Europe might expect may be found in their recent experience, which we have charted using our Chief-Exec.com energy-dissipative analysis of the pandemic.

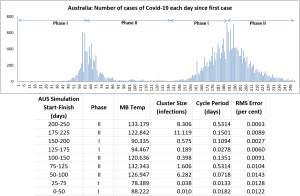

Briefly, in all countries we have observed, that as the pandemic spreads, it oscillates between two distinct thermodynamic phases. In Phase I, a cooler virus exhibits the potential for exponential growth of infections. In Phase II, the virus is heated and its infection rate appears to diminish, as has been observed at times of national lockdown.

Australia

In the chart below, Australia provides a typical example of how the coronavirus passes between Phases I and II, through the two waves of viral infection that the country has encountered.

For further information on this presentation of the coronavirus infection data click here.

In the broadest terms, the two spikes in Australia are the result of two unrelated incidents where control measures broke down at a particular time and place, a former ministerial advisor told Chief-Exec.com. The first, beginning around mid-March, was the Ruby Princess debacle in Sydney when 2,700 passengers from a coronavirus infected cruise ship were released into the city and beyond without quarantine. At the time there was a low, but manageable level of infection in Australia across most states and territories. The first spike can largely be attributed to that outbreak and, while some passengers spread though Australia, many of the infections remained in Sydney.

In the wake of that first wave, infection rates finally subsided. Daily cases fell back to manageable levels and the pattern of viral infection reverted to a Phase I behaviour setting up the conditions for a second wave to flare up when further initiating events occurred.

“The more recent spike in the second half of June was almost entirely the result of the failure of quarantine arrangements for Australians returning to Australia via Melbourne,” the former advisor, who asked not to be named, said.

“Private security guards were engaged to control the guests in two hotels. The poorly trained and supervised guards spread infection across Melbourne, ultimately requiring draconian measures to bring the epidemic under control.”

This increased intensity of viral infections during that second wave is associated with a larger simulated cluster in Phase II regions in the above chart – a feature that is common with all other countries studied to date.

The pattern of the second wave followed closely that of its predecessor. Confinement measures restricting outdoor activity only to essential activities – as seen in European lockdowns – worked well when adopted with the necessary force.

“In both outbreaks in Australia, the fundamental cause was a breakdown of official controls, poor communication between multiple federal and state agencies, unclear lines of accountability and abrogation of responsibility – all in a fast-moving situation,” the former advisor said.

In terms of the distinctive aspects of Australian control measures, there has been a willingness to close internal state borders and prevent travel between population centres.

“Also, there was a clear national consensus from the initial stages which, apart from the specific incidents mentioned above, kept levels low.

“There has been a consistent approach to keep messaging to the public simple and clear, together with a fast and firm approach taken by all jurisdictions, and across the partisan political divide.”

The former advisor said that, despite the inevitable urging of some enthusiasts for free market solutions, all Australian governments focussed on the need to fix the health issue in order to get the economy back in shape in a sustainable way. There is widespread community support (about 65 per cent) for prioritising health over premature economic recovery.

“The emphasis is now on testing and tracing, but varying degrees of isolation are in place across the states as a preventative measure.”

New Zealand

In New Zealand the pattern of coronavirus infection is similar to that observed in Australia and likewise was initiated by specific events that compromised border security.

The chart for New Zealand shows that the daily infection rates were highly attenuated by the early and tight restrictions placed on the daily life of New Zealanders.

For further information on this presentation of the coronavirus infection data click here.

Very early confinement compressed the initial Phase I to less than 50 days – earlier than in other countries – which limited the intensity of the first wave. Subsequently, the estimated characteristic cluster size was held at low levels as the virus switched between Phase I and II behaviour. A smaller second wave centred on about 179 infections in Auckland in early August. Residents of the city were immediately instructed to stay at home apart from essential movement.

This proactive approach appears to have suppressed the emergence of a second wave that was seen in neighbouring Australia.

This week most restrictions were lifted in Auckland and Covid-19 was again declared “under control” in New Zealand after no new cases in 12 days, prompting Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern cautiously to acknowledge: “Aucklanders and New Zealanders stuck to the plan that has worked twice now and beat the virus again”.

Over the past 250 days, the country has recorded 25 deaths due to Covid-19.

How did New Zealand achieve this? “Our team of five million, a little more battle-weary this time, did what national teams do so often. We put our heads down, and we got on with it,” Prime Minister Ardern told reporters in Christchurch. She called the reopening of Auckland a validation of the country’s “go hard, go early” response – a strategy aimed at eradicating the virus with a swift science-based policy that trades weeks of lockdown and sacrifice for a return to a sustainable economic activity.

This explanation echoes the advice offered early in the coronavirus pandemic, in March, by Dr Mike Ryan, Executive Director of the World Health Organization, when asked what lessons can be drawn from his earlier experience with Ebola virus.

“React quickly … stop the chains of transmission … be the first mover, … perfection is the enemy of the good … the greatest error is to be paralysed by the fear of failure,” Dr Ryan said.

“Be fast, have no regrets.”

Dr Michael J Ryan says “the greatest error is not to move” and “speed trumps perfection” when it comes to dealing with an outbreak such as #coronavirus.

Get the latest on COVID-19 👉 https://t.co/HMPNwaVk37 pic.twitter.com/wDa7XOMw8Q

— SkyNews (@SkyNews) March 13, 2020

As island nations on the opposite side of the world to Europe, Australia and New Zealand are in an enviable position of having a large degree of control over their own borders. Notwithstanding this, for both countries, it was unanticipated losses of that control that caused clusters of infection to flare up.

By reacting quickly to these events, their Governments proved effective in protecting their citizens.

For related articles on Chief-Exec.com : Click Here

Headline Photo Credit: © E-Tech Limited 2020