The people have spoken and the “Brexit Election” campaign of the Conservatives in the UK will go down as one of the most successful in recent history. The number crunching will go on for days, but already the outcome is heralded as a huge victory for democracy. But it may be quite the opposite.

In fact, democracy itself may be doomed, writes John Egan.

This is a conclusion that shook the academic world of cognitive psychology last summer when eminent veteran Shawn Rosenberg, Professor of Political Science and Psychological Science at the University of California, presented his latest ideas to an international conference in Lisbon. The outrage that followed was reported in detail in PolitcoMagazine.

“Our brains,” according to Rosenberg, “are proving fatal to modern democracy. Humans just aren’t built for it.”

Humans consequently harbour all sorts of prejudice. They tend to absorb information that supports their beliefs and filter out anything that brings them into question. This leads to a vulnerability that can be exploited by the many variants of snake-oil salesmen.

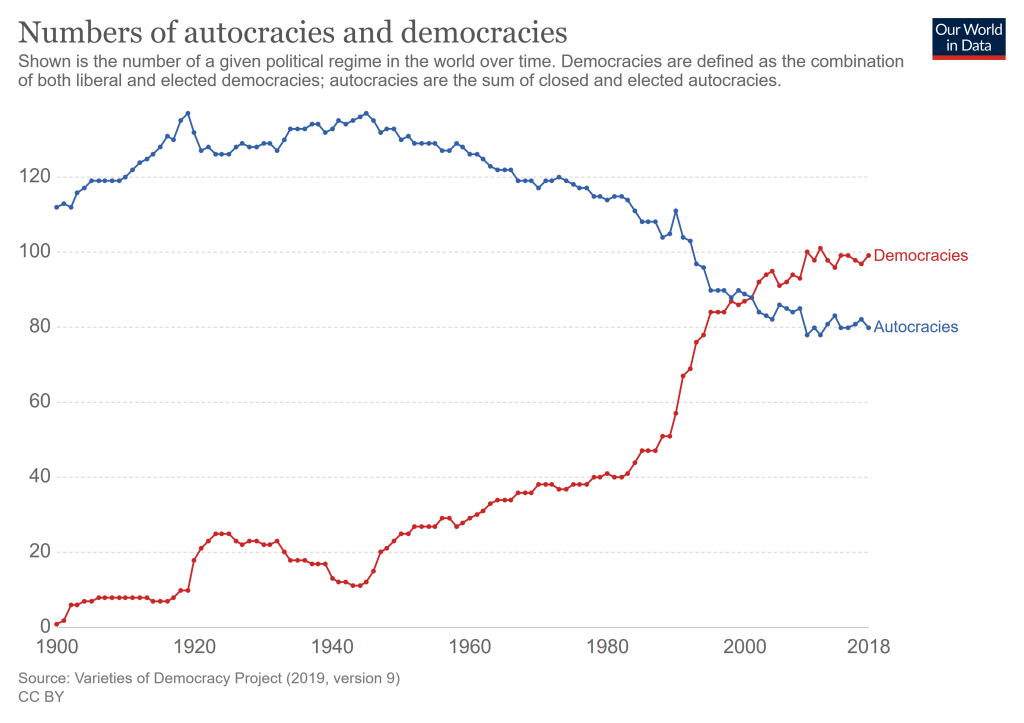

Compelling data shows that across the world over the past 70 years, the number of democracies has increased from 12 in 1945 to 99. It seems like the democratic model of providing government “of the people for the people” is becoming universal.

Max Roser (2019) – “Democracy”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. CC license 4.0

However, Rosenberg points to the onerous demands democracy places upon the people that enjoy its virtues. They must be intellectually vigilant and have the capacity to keep well informed – to distinguish between true and false.

To overcome their limitations, democratic societies have divested these lofty responsibilities, in part, to their institutions, to academics, politicians, journalists and “experts”. And it is here that Rosenberg identifies the seeds of the demise of contemporary democracy.

According to Rosenberg the rise of populism around the world is not accidental, but is caused by the weakening of those institutions that carry the intellectual weight of democracy for the people. Individuals themselves are then left to do the necessary hard yards.

Democracy demands a sense of nuance and compromise, while recognising diversity and different points of view. It is for this that the man on the Clapham omnibus is so poorly equipped, cognitively speaking.

David Moscrop is another political theorist who addresses the same subject with his provocatively titled video and book Too Dumb For Democracy published this year.

Moscrop’s argument rests on an assertion that our brains have evolved to deal with simple matters and have not changed greatly for millennia. They are simply ill-equipped to deal with today’s highly complex matters and make the judgements democracies need for beneficial outcomes. For example, “Getting Brexit Done” is not as simple as it sounds.

According to Moscrop, the optimistic foundations of democracy, from antiquity to the enlightenment, see the people as compassionate, calm, rational and reasonable political decision-making machines. In reality, not only do our passions and prejudices grossly distort the rationality that is needed, but there are also people whose job it is to “know how you think and how you make decisions, to hijack that process to get you to vote for their candidate, to support their issue”. It is manipulation not persuasion.

The way to save democracy from its impending demise is more democracy to counter the increased insolation of individuals in society, says Moscrop. This requires individuals to make the effort to reflect upon why they have made this or that decision and try to understand the motivations of others who see the world differently. To listen to the radio and read articles normally avoided and to test one’s own convictions. Democracy depends on citizens taking the time to do this job.

Moreover, Government needs to do much more to bring citizens into the decision-making process to build a civic capacity for informed decision making.

Is this realistic or even necessary?

Following this advice of David Moscrop, we can seek out counter-opinion in an article by Kevin Baldeosingh who writes a vehement critique of the thesis of Shawn Rosenberg.

The tendency to consider most people as being stupid and ignorant, and dependent on an expert elite to make important decisions, is typical of such a self-proclaimed elite that has always mistrusted the people, he says.

Citing the famous social psychologist Drew Westen from his book The Political Brain, the lessons of history show “the empirical record linking moral action and intellectual rigor isn’t very strong”. For Baldeosingh, the approach of Rosenberg draws its inspiration from Plato’s ideal of a city governed by philosophers who, in reality, turn away from democracy when it does not suit their own desires.

So, is democracy doomed because the people are naturally too dumb to save it, or is it worth making the effort to save? Or is this simply the siren sound of experts who have been discharged by the people from their role in protecting their interests?

The future evolution of Brexit might well supply the necessary insights to answer that question.

Headline Photo Credit: Amani A /Shutterstock.com

Acknowledgements: Brice Couturier and France Culture