Within sections of the international business community which applauded Britain’s vote to leave the European Union there is intense puzzling about what appears to be a glaring contradiction in the May Government’s post-Brexit thinking.

Reports that Britain will seek to remain a participant in the EU’s Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) – the cornerstone of European climate action – are causing alarm, particularly among corporate campaigners seeking to roll back the “regulatory burden” they say has been imposed on business by over-zealous climate change forces.

The May government hasn’t declared its hand on the future of British involvement in the ETS. But recent reports have suggested that the government is very likely to decide to seek to negotiate an arrangement under which Britain could remain within the system.

The UK government’s own climate advisory body, the Committee on Climate Change, has said that the EU’s ETS may be the “least cost option” for regulating British emissions without creating competitiveness challenges for British Industry.

British industry groups, including the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), have called for continuity in Britain’s carbon reduction system.

To European Union officials, the possibility that Britain would want to retain its involvement in the ETS is perfectly understandable and, sources say, is an open question. They point out that British involvement in the scheme has been fundamental to its evolution because Britain is Europe’s second largest CO2 emitter and therefore vital to the successful operation of the permit trading system. (Under the ETS, permits for “dirtier” industries to emit greenhouse gasses are traded across borders with industries with low emissions within limits set by the EU.)

But in other parts of the world where hard-line neo-liberal economic thinking is much more pervasive than in Europe – in the United States and Australia in particular – the British decision to quit the European Union is seen as a golden opportunity to extract Britain from the climate change policy “morass” for which the EU, it is felt, is chiefly responsible.

With President-elect Donald Trump declaring his intention to roll back environmental regulation – especially that targeting coal – and signalling that he is likely to withdraw the US from the Paris agreement on climate change, climate change policy critics argue that the tide is turning against heavy-handed regulatory regimes.

The US’s leading climate change denial think-tank, The Heartland Institute, has welcomed the Trump presidency as the beginning of the end of the “hoax” of man-made climate change.

In Australia, advocates of bold action on climate change have been in retreat for several years and have just lost another battle. The conservative Liberal-National Party government last week rejected advice from the government’s Chief Scientist that the best approach to dealing with Australia’s high emission levels was to introduce an emission intensity scheme for electricity generators across the country.

Australia’s per capita CO2 emissions levels, at 17.3 tonnes a year, are the highest in the industrialised world, higher even than the US which emits 16.5 tonnes a year. Across the EU the annual rate per capita is 6.7 tonnes.

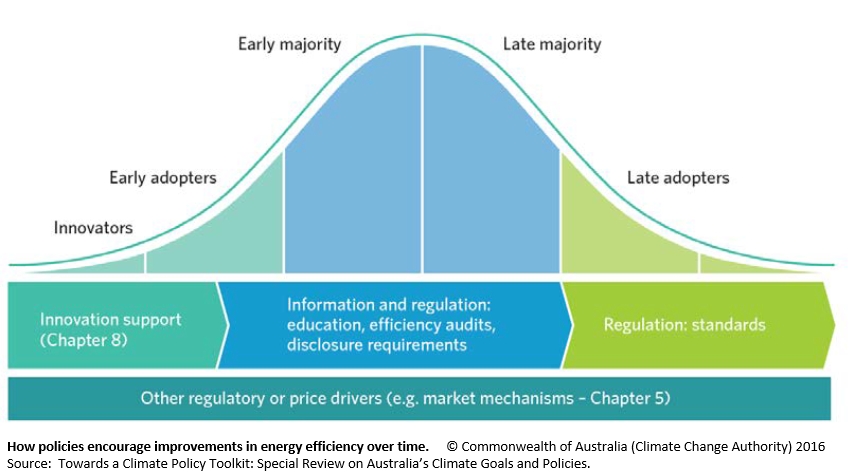

The Australian government’s own Climate Change Authority has also called for stronger action to reduce emission levels, warning that the later businesses left it to act to cut their own CO2 levels the more internationally uncompetitive Australia would become.

The CCA report produced a compelling chart showing how businesses which were early adopters of emission reduction strategies gained advantage over those that delayed.

But as a nation, Australia has gone from being a leader in responding to climate change to a laggard.

After ambitiously moving to introduce a national emission reduction scheme in 2008, which was followed by extraordinary political upheaval that saw five prime ministers dumped in eight years (with the current PM Malcolm Turnbull in serious trouble), Australia is now relying on a so-called “direct action” policy under which polluters are paid by the government to cut emissions. The government’s own experts have warned this will be insufficient for Australia to meet its 2005 emission target to reduce levels of CO2 by 26 to 28 per cent by 2030.

Climate change policy has been heavily influenced by a strong and vocal minority of climate change sceptics, the most outspoken being Maurice Newman, a former chairman of the Australian Stock Exchange and a former head of the Prime Minister’s Business Advisory Group.

Newman has claimed that global warming is a United Nations created conspiracy to hobble global capitalism and create a one world, authoritarian government. He is also a strong supporter of Brexit and a fierce critic of the European Union that he says is a “relic of post-war French hubris, created to keep Germany under control”, which was plainly unravelling and which Britain was very wise to cut itself loose from.

The power of the climate sceptics and denialists was increased at the recent Australian election when a far-right party – One Nation – won four Senate seats and a share of the balance of power in the Parliament.

One Nation supports the claim that the United Nations is a front for a global one-government conspiracy and has demanded that Australia’s Great Barrier Reef be removed from the UN world heritage protection to free it from the clutches of the UN. Despite this (or maybe because of it) the party is forecast to win a swag of seats at the forthcoming Queensland state election.

Although there are strong calls from the business community that Australia should be following Europe’s lead on acting on climate change and preparing for a decarbonising world, these voices are proving ineffective against the newly powerful opponents of action.

Given that climate change scepticism and denial appear to be a feature of the far-right populist political movements emerging in western democracies, Europeans who favour strong regulated action to deal with climate change should beware.

by Geoff Kitney

Headline photo: Yallourn W Power Station, Victoria by Malcolm Paterson

Supplied by CSIRO Science Image

Used under the terms and conditions of Creative Commons license