Will humans soon be dreaming of electric sheep, asks James Fitzgerald.

Beyond the angry headlines on immigration lies a more subtle movement that promises to usher in a population explosion – of animated human pretenders.

Even if we look past the theatre of war, and focus on the social and cultural implications of machines, we are still faced with the philosophical and legal proposition: what is the acceptable face of robotics?

And, depending on which side of the globe you are standing, the answer will be different. As the American author Daniel H. Wilson put it: “In the United States we are terrified by killer robots. In Japan people want to snuggle with killer robots”.

It takes an examination of Japanese culture and history to reveal the archetypal forces that drive its preoccupation with socially desirable simulated humans. While in the Anglo-Saxon world it is the industrial potentials that excite the most interest, both cultures’ evolutionary tracks can be traced back to religion.

The social scientist Naho Kitano cites animism – a facet of the Shinto faith – as an influential component in the Japanese psyche. Animism proposes that all objects – even inanimate ones – have a spirit.

“From the prehistoric era, the belief in the existence of spirit has been associated with Japanese mythological traditions related to Shinto,” Mr Kitano wrote in a paper for Waseda University in Tokyo in 2006. “This thought has continued to be believed and influences the Japanese relationship with nature and spiritual existence. This belief later expanded to include artificial objects, so that spirits are thought to exist in all the articles and utensils of daily use, and it is believed that these spirits of daily-use tools are in harmony with human beings.”

The Western subconscious has been permeated with ideas from the Judeo-Christian tradition, which posits that only God can create life. The conventional interpretation of Genesis is that there was only God in the beginning and He created all life. Exodus furthers this concept with the decree that idolatry is a sin. Therefore, the subtext of science fiction has often been that anyone who breathes life into an inanimate object is assuming the role of God, and becoming a false idol. This blasphemy is punished by the inevitable betrayal of the robot – from Blade Runner to The Terminator.

As part of that innate behaviour …… it is often our default behaviour to anthropomorphise moving robots

With the creation of “life” comes the karmic responsibility for its effects in the world. Mary Shelley’s character Victor Frankenstein was made to feel the emotional and existential torment of his haphazard creation. As with an over-refined sugar cube, the depleted molecules will seek to regain wholeness by leaching electrons and minerals from the consumer’s body. Perhaps this impulse also lies within the synthetic “consciousness” of the machine?

The Czech playwright Karel Capek – in his 1920 play Rossum’s Universal Robots – coined the term “robot” to describe the synthetic humans of his story – who eventually rebel against their makers.

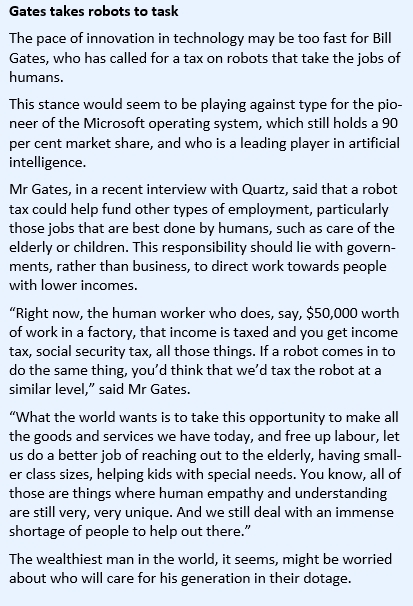

This haunting vision of robots may be occupying the minds of European Union parliamentarians, who have just voted on new rules and laws to govern their use. A report by the legal affairs committee calls on the European Commission to produce a legislative proposal to deal with issues such as who should be liable if someone gets hurt by robots. The report’s author is Mady Delvaux, who is an MEP with the socialist and democratic group in Luxembourg.

“We define robots as physical machines, equipped with sensors and interconnected so they can gather data,” said Ms Delvaux. “The most high-profile ones are self-driving cars, but they also include drones, industrial robots, care robots, entertainment robots, toys, robots in farming.”

“We define robots as physical machines, equipped with sensors and interconnected so they can gather data,” said Ms Delvaux. “The most high-profile ones are self-driving cars, but they also include drones, industrial robots, care robots, entertainment robots, toys, robots in farming.”

Her report proposes that robots should have a legal status. But what does that mean? “When self-learning robots arise, different solutions will become necessary and we are asking the Commission to study options. One could be to give robots a limited ‘e-personality’, at least where compensation is concerned. It is similar to what we now have for companies, but it is not for tomorrow. What we need now is to create a legal framework for the robots that are currently on the market or will become available over the next 10 to 15 years.”

Dr Heather Knight is devoted to social robotics — the study of how robots and humans interact today, and how this relationship might develop in the future. She is the founder of the Marilyn Monrobot Lab in New York, which creates robots with social sensibility that are designed to entertain an audience. In a doctoral research paper for Carnegie Mellon University – “How Humans Respond to Robots” – she espoused the need for humans to care about robots.

“Robots do not require eyes, arms or legs for us to treat them like social agents. It turns out that we rapidly assess machine capabilities and personas instinctively, perhaps because machines have physical embodiments and frequently readable objectives. Sociability is our natural interface, to each other and to living creatures in general. As part of that innate behaviour, we quickly seek to identify agents from objects. In fact, as social creatures, it is often our default behaviour to anthropomorphise moving robots.”

She places robots in a social context, where our acceptance of them and, more importantly trust, will be critical to their full adoption by society. The technology to fully automate transportation and manufacturing already exist, but until people develop trusting social and professional bonds with these machines, they will remain outside our core experience.

Dr Knight says that iRobot, the maker of Packbot bomb-disposal robots, has received boxes of shrapnel in the post following an explosion with a note from the soldiers asking, “Can you fix it?”. Either the soldiers are expressing a dry sense of humour, or they have felt grief at the “death” of their metallic comrade.

We proposed a charter setting out that robots should not make people emotionally dependent on them. You can be dependent on them for physical tasks, but you should never think that a robot loves you or feels your sadness

It may be beholding on manufacturers of social robots to protect their owners from the risk of social isolation. “Robot intelligence and simulated social behaviours are simplistic compared to the human equivalent. One cannot supplant the other, and protections should be in place to avoid a social over-reliance,” writes Dr Knight.

Ms Delvaux would also like to short-circuit notions of emotional attachment to robots from the outset. “We always have to remind people that robots are not human and will never be. Although they might appear to show empathy, they cannot feel it. We do not want robots like they have in Japan, which look like people. We proposed a charter setting out that robots should not make people emotionally dependent on them. You can be dependent on them for physical tasks, but you should never think that a robot loves you or feels your sadness.”

Notions of robots as somewhat dangerous is hardly surprising in the West, where their development has often been part of a military agenda, but in Japan their spiritual status posits them firmly as benevolent companions in a technocratic world – particularly as an ageing population becomes increasingly dependent.

We’ve put man on the moon, and now a robot has made it onto the International Space Station. Nasa has unveiled a new generation of “robotic free fliers” that will be of practical help to humans in space. Its designers say the Astrobee will operate safely and autonomously on the ISS.

The Astrobee, which has a CO2 propulsion system that operates both inside and outside of the station, can perform a variety of tasks, in some cases taking over boring housekeeping jobs from the astronauts. In the cramped and disciplined environment of a space station, its inclusion is a vote of confidence from the cadre of space explorers.

Back on Earth, researchers at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science in Tsukuba, Japan, are hoping to address the issue of falling bee populations with, wait for it, robo-bees. The mini drones sport horse hair and a sticky gel that could be used to transport pollen from one flower to the next. The concept could be viewed as a sticking plaster solution to a serious ecological problem – and perhaps demonstrates a degree of myopia in some areas of the scientific community.

To my mind, robots have one big advantage over humans: their social decorum – they don’t burp, fart or pick their noses – at least not yet.