Capital in the 21st Century is a surprising international best-seller. A highly detailed monograph from the renowned French economics professor, Thomas Piketty, the 690 page book seems an unlikely source for such global popularity. It is packed with data, illustrated by multiple graphs and interpreted through an interwoven narrative that provides a vision of the future that is more of a return to the past than a triumph of technical prowess.

It should be recognised at the outset that controversies abound in historical economic data and its interpretation, particularly in estimations of wealth (for example, see Alvaredo et al.). Yet this does not undermine the power of the data. Its interpretation is impressive and the book is deserving of its celebrity status.

In a series of articles for chief-exec.com we will unstitch some of the themes of Piketty’s economic tapestry to help our readers understand what this could mean for the future of their business or even how they might lead their lives.

We will use the original data made available on Thomas Piketty’s website to link chief-exec.com readers to the Capital in the 21st Century manuscript.

Born in Unusual Times

One’s experiences through life have an inevitable influence on perceptions and how we understand the world in which we live. Implicit in this cognition is an assumption that this external world is normal – a standard reference.

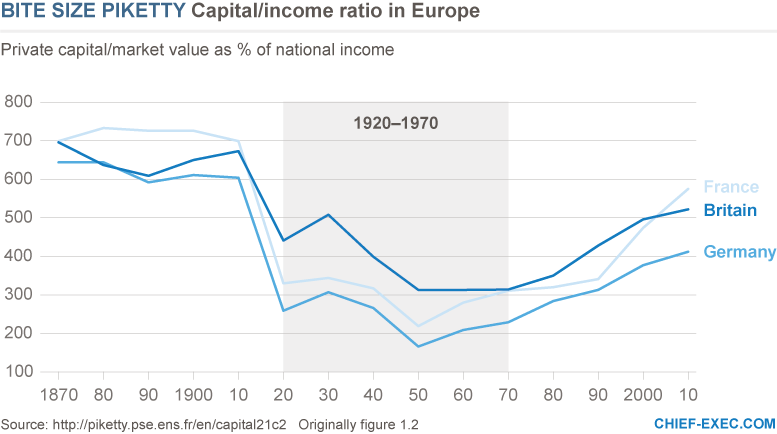

A startling observation exposed in Piketty’s data is that people born in the 50 years between 1920 and 1970 were delivered into quite extraordinary times in which some fundamental economic behaviour differed from preceding centuries and millennia.

This observation appears in Figure 1.2 in the variation of Value/Income ratio for three European countries from 1870 to 2010. This graph begins with the value of all capital assets owned by a country being around seven times the annual income (approx. GDP) of that country. It is a trend that hardly changed for at least a century. Suddenly, in about 1915 there was a precipitous and unprecedented drop in this Value/Income ratio. Only in about 1970 does this dip begin to reverse.

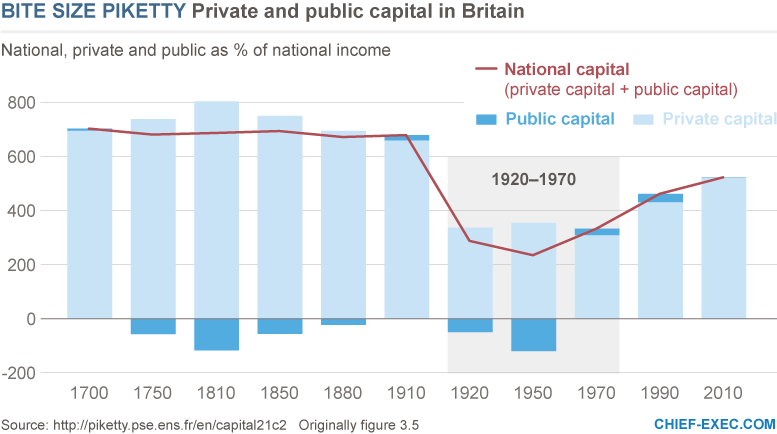

The same pattern appears in Figure 3.5 showing the value of private and public capital – and the sum of these which is the national capital for Great Britain – over two centuries. This graph confirms that it was a massive destruction of value in national capital assets through the first half of the 20th century that was the cause of the huge economic upheaval. The capital destruction of two world wars, together with an intervening Great Depression, caused the collapse of value of both private and public capital.

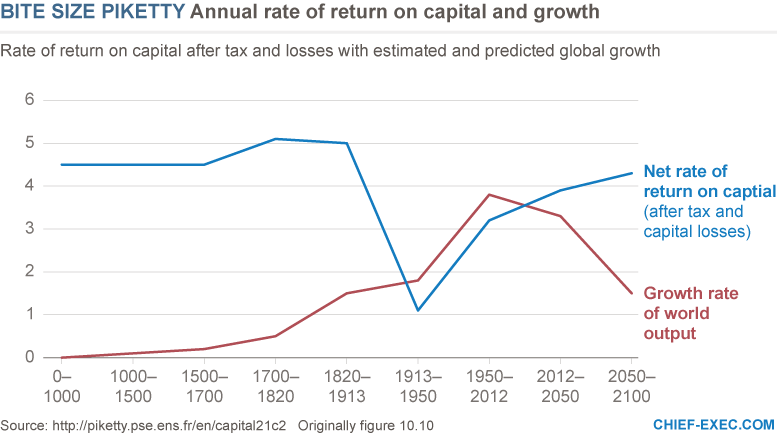

Taxation also played a particular role in the unfolding story. While pre-tax rate of return on capital assets has remained relatively constant at about 4-5 per cent for millennia, Figure 10.10 shows an appreciable fall in post-tax return on capital to around 1 per cent. Uniquely at this time, tax on capital was used in global reconstruction following the wars of the 20th century, as well as to encourage a new found equality of citizens who had so recently been comrades in arms. It required the adoption of neo-liberal economic policy post-1980 for taxes on capital assets to begin to return to pre-conflict levels. The post-war reconstruction, together with the adoption of modern innovations that enhanced quality of life, led to a period of sustained high economic growth.

For 50 or so years in the known history of mankind, the economic growth rate exceeded the rate of return of capital. Uniquely and briefly the earning power of labour superseded that of capital and one was able to perceive:-

- The definitive end of an upstairs-downstairs Victorian society with their huge separation of rich and poor.

- A meritocratic society in which those that worked hard earned enough to “do well”.

- An almost infinite belief in the power of innovation to improve quality of life, with the impression that subsequent generations would have a continually higher standard of living.

- A belief in the power of education to enhance what would later become known as human capital, so that a good life could be found through education and an economic contribution to a modern society.

Are there any “baby-boomers” reading this article who have not harboured these presumptions?

The above charts suggest that the modern world viewed from a mid-20th century perspective was a chimera. Recent trends indicate a reversion to the past. Piketty suggests that, to understand how individuals might lead their lives in the future, one might better consult the works of Jane Austin and Honoré de Balzac, rather than possibly George Orwell and Gene Roddenberry – except in taking the Road to Wigan Pier.

But there are also distinct differences between times past and those to come. For example, the composition of capital holdings has changed from land to property and assorted financial assets. The old are getting older and richer as a consequence. These differences and more will be covered in subsequent articles that make up this digest of Capital in the 21st Century for the chief-exec.com readers.

by John Egan