The cheers that greeted Theresa May’s declaration at the Conservative party conference on the weekend when she declared Britain would return to being a “fully independent, sovereign country” rang hollow not just in Brussels but in key power centres around the world.

No more so than in the corridors of the institutions that make up what has become known as the “rules-based system of global order”.

It’s not just the European Union’s policy makers and diplomats who are feeling the shockwaves of the Brexit vote. Their counterparts at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the United Nations are all just as uneasy and alarmed. So are the proponents of global action on climate change who fear the future of their cause in the event of a Donald Trump presidency in the US.

Prime Minister May’s blunt re-assertion of Britain’s intention to make its own way in the world is being seen by those who work within the various institutions which comprise the global rules-based system as a potentially dangerous landmark in the long evolution of the globalisation process.

While May argues that, post-Brexit, she wants Britain to be “the global leader on free trade”, the view among those involved in trade diplomacy is that Britain is likely to be much less a force for free trade outside the EU than in it.

“Globalisation has only been possible because nation-states have been prepared to cede sovereignty to allow the free movement of trade, investment and people,” a senior Geneva-based trade diplomat told Chief-Exec.com. “In Brexit, we are seeing the most dramatic manifestation of a retreat from that process.”

The Brexit vote, he said, was the result of popular opinion turning against a system of integration which had fundamentally benefited Britain but which had resulted in changes that had become unsettling and easily exploited by the opponents of the integration of Britain into Europe.

This was symptomatic of a mood developing throughout the developed world, which threatened to overturn the rules-based international order, not just for trade but for the whole system of globalisation.

“I think we are entering a very dangerous period for the world,” he said.

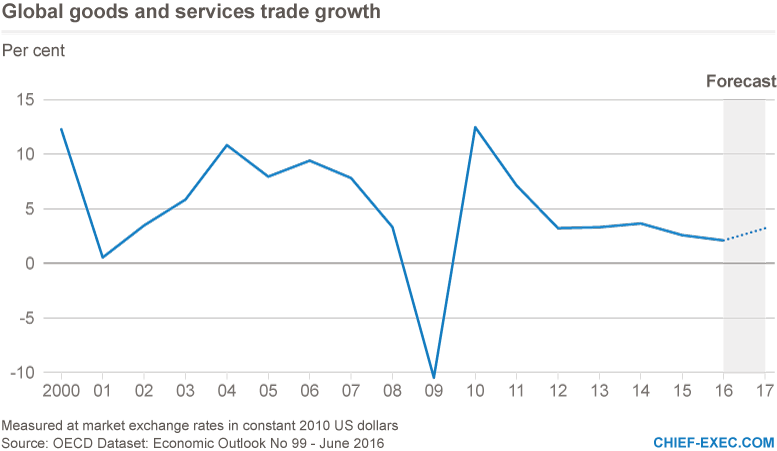

The most recent figures on world trade published by the WTO and the OECD’s latest analysis of the state of the world economy give substance to the concern of trade diplomats and policy makers.

Between 1980 and 2007 there was an eight-fold increase in global trade. Since the global financial crisis, global trade has slowed dramatically. Global trade is forecast by the OECD to increase by just 3.2 per cent next year, below the forecast for overall economic growth.

Trade officials say that the slowdown is, to a significant degree, the result of rising protectionism, a trend that is likely to increase after the US election, regardless of who wins.

Some insiders believe that the possibility that the US will relinquish its global leadership role on the liberalisation of trade and investment must be confronted by European leaders because of the high stakes the European Union has in sustaining multilateralism. A populist-driven retreat behind higher national borders against movements of trade, investment and people would present an existential threat to the European project.

The optimistic view of this is that the May government and the EU leadership will recognise their mutual interest in negotiating a trade and investment treaty that is liberal and growth-enhancing – and which stands against the tide of populist opposition to globalisation.

This would not be easy, not least because of the problem of devising a system that allows for free movement of goods and money but not of people.

The political climate in Europe seems set to turn even more inclement for economic liberalisation as right-wing populists loom large in coming elections in the major EU countries and political leaders turn against the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and its Canadian equivalent CETA free trade agreement.

In this climate, who would be the leaders who would stand against such a tide? That will be the real leadership test for Europe as the Brexit process unfolds over the next couple of years.

By Geoff Kitney