The world seems to get more uncertain each week. Momentous changes are in the air – or have already happened. It’s not surprising if you’re unsettled and feeling powerless to influence things. Many people feel they can’t control their own lives, let alone world events.

And yet you probably know someone (perhaps you!) who thrives on the challenge of uncertainty. They are motivated by time pressures and the need to act decisively in the face of great risk.

I’ve found that understanding how these differing responses arise is the key to coaching people through change. And, if your job is about influence and leadership, then that insight is critically important.

Uncertainty causes us distress, at least when it’s our own welfare that’s uncertain. But some people are skilled at manipulating events, taking advantage of a state of flux to advance their own agendas and careers. Consider Jeremy Corbyn and Donald Trump. Neither was rated as a serious contender for power just over a year ago, but both have managed to divert the “normal“ processes of their respective political systems by seeming to be different.

In all fields, the status quo tends to be maintained until something unforeseen disrupts it. This principle was expounded by Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions where he developed the idea of a “paradigm shift” that overturns the prevailing consensus. Perhaps we’re experiencing a paradigm shift now in politics, economics and society generally. Or, maybe, the old order will re-establish itself eventually – to the relief of some and the disappointment of many.

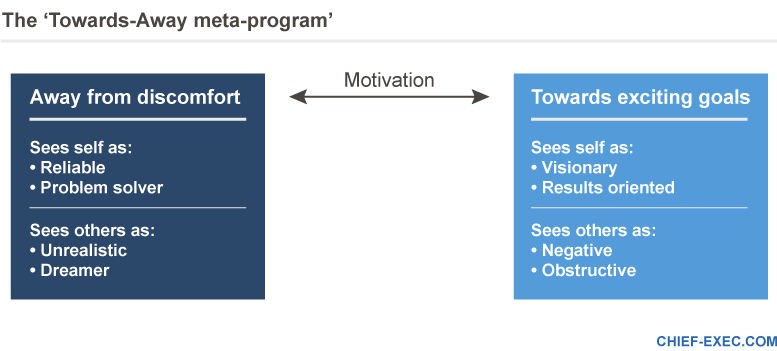

Whether you fear change or welcome it depends on which end of the various “meta-program” ranges you sit. Particularly relevant meta-programs here are “Towards-Away” and “Options-Procedures”.

Away motivated people take action to avoid discomfort, so they like to keep things the same. Towards motivated people strive towards exciting goals; they like to make things happen.

Options people want choices and are good at developing alternatives. Procedures people are good at following set courses (they read the instructions!) and are not action-motivated.

As with all meta-programs, we are all capable of thinking at either end of the spectrum, but we tend to have strong, individual preferences for one style.

These differences in how we respond to change are also interpreted in the Kirton Adaption-Innovation Inventory (KAI). Adaptors like to do things better by improving procedures. Innovators like new things and new ways, not because they are necessarily better, but because they are different! (So be aware, innovation isn’t always a good thing!)

Evolution (or nature generally) is very hard on species that can’t adapt to changes in their environment. The American philosopher Eric Hoffer famously summed up how this translates into individual human development: “In a world of change, the learners shall inherit the earth, while the learned shall find themselves perfectly suited for a world that no longer exists”.

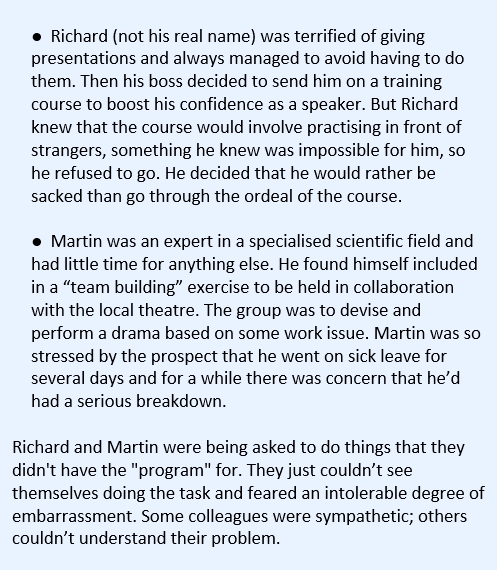

Humans have the ability to learn new skills through the establishment of mental “patterns”. This is the “programming” part of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP). We don’t have enough conscious brain-power to be aware of everything we need to do, such as breathing, maintaining balance, noticing threats whilst at the same time responding to other people and adopting appropriate body language. We have to set up “automatic” patterns that our brains can follow unconsciously, leaving the conscious mind to get on with whatever we’ve chosen to do.

Humans have the ability to learn new skills through the establishment of mental “patterns”. This is the “programming” part of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP). We don’t have enough conscious brain-power to be aware of everything we need to do, such as breathing, maintaining balance, noticing threats whilst at the same time responding to other people and adopting appropriate body language. We have to set up “automatic” patterns that our brains can follow unconsciously, leaving the conscious mind to get on with whatever we’ve chosen to do.

What causes us a lot of trouble is that the patterns that govern our social behaviour (in the broadest sense) can become out of date and inappropriate to changed circumstances.

Because the patterns are unconscious we don’t perceive them as things we once chose to do – rather we take them to be part of “the kind of person” each of us thinks we are. If you believe that you can’t change that person then you are trapped in a system of behaviours that obstruct rather than support you.

If this is a good model of how humans work, then try looking at some of the big events in the news now through that lens. Can you see people trapped in patterns of thinking and doing that they won’t, or more likely can’t, change?

Perhaps then the most useful skill of all is the ability to recognise that even deeply embedded behaviours and strategies can be changed – and then knowing how to change them.

By David Rawlings

Email: david@changeworkcoaching.com

Email: david@changeworkcoaching.com