In 51 minutes and with 15 references to “productivity” the UK Chancellor Philip Hammond threw more light on what a post-Brexit Britain could look like than all the uncountable hours of hints and hedges that went before.

Not bad for an Autumn Statement that has been recognised as unflashy.

The financial statement aims to change the course of the British economy to become an efficient, innovative and open-trading nation. A Singapore-like UK trading freely on the doorstep of Europe remains a distant vision, but the compass has been set and the weather has been forecast.

Financial headwinds have been predicted by the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) in its independent forecast recognising the major uncertainties incurred by leaving the European Union. Lower than expected taxes and higher spending, together with Brexit-related effects of reduced GDP and lower migration, will push government borrowing for 2016 to 2021 up by £110.2 billion – that is over and above the £106.1bn forecast made last March (1).

Over these five years, the estimated cost to the British taxpayer of leaving the EU will be £58.6bn (£225 million a week).

In a briefing note, OBR chairman Robert Chote pointed out that, rather than wielding spending cuts or tax increases in response to such a deteriorating budget outlook, Mr Hammond has taken a more unusual tack to increase borrowing by a further 0.4 per cent of GDP. In doing so, the chancellor has needed to adjust the target of his predecessor, George Osborne, of achieving a budget surplus by 2020, to accepting a continued debt that is below 2 per cent of GDP by that same year.

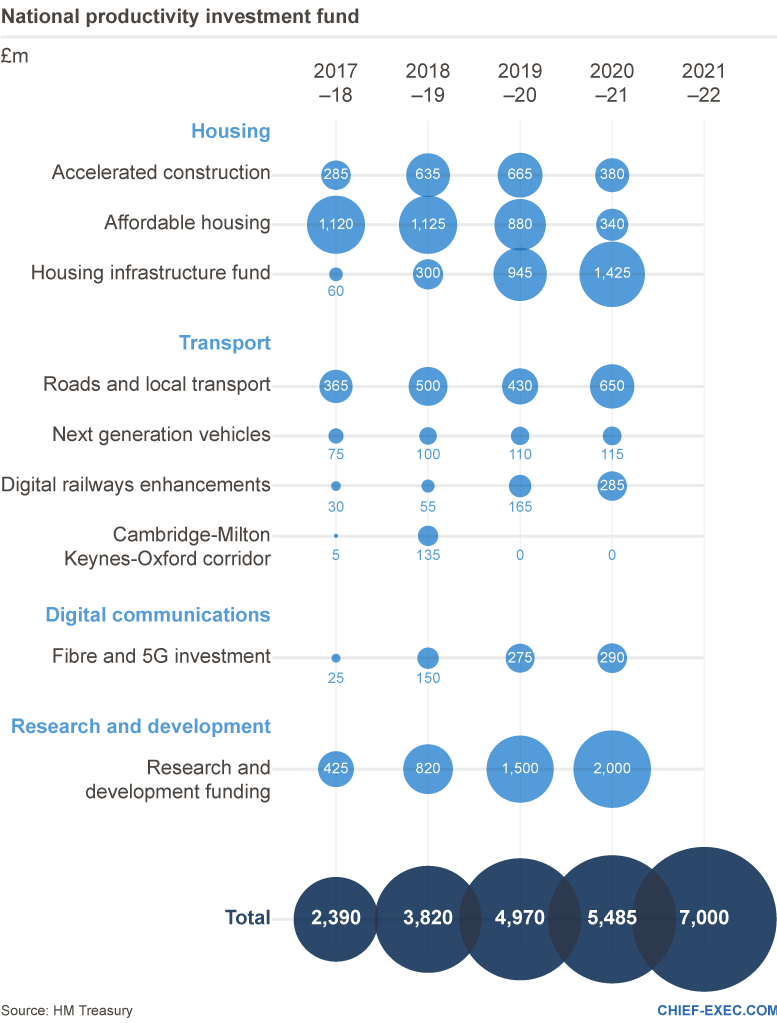

This move has given Mr Hammond an extra £50bn to spend over the next five years. He is putting £27bn of this away for a rainy day in case the future holds some unpleasant surprises. The remaining £23bn he has allocated to a National Productivity Investment Fund (NPIF) that is intended to create the foundations for a productive post-Brexit economy.

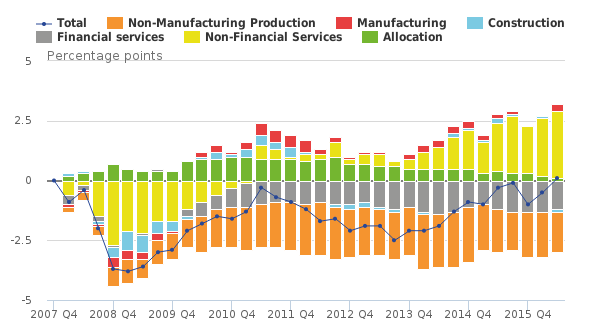

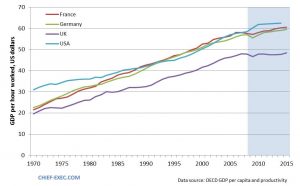

In its October economic round-up Chief-Exec.com pointed to a “puzzle” that is inhibiting the return to productivity growth in the UK after the 2008 downturn. As a result the long enduring “productivity gap” with France, Germany and the US has widened in recent years. What a UK worker can make in five days, a worker in Germany or France can do in four. The NPIF is intended to address this issue.

In its October economic round-up Chief-Exec.com pointed to a “puzzle” that is inhibiting the return to productivity growth in the UK after the 2008 downturn. As a result the long enduring “productivity gap” with France, Germany and the US has widened in recent years. What a UK worker can make in five days, a worker in Germany or France can do in four. The NPIF is intended to address this issue.

The NPIF’s £23bn will be divided into the activities listed in the table below that free up the flow of people (housing and transport), information (digital communications) and innovation (R&D). The rationale is the same as the problematic European principle that the free movement of the factors of production is essential for a productive and prosperous society.

The same principles also apply to regions in the UK. In his Autumn Statement, Mr Hammond said: “no other major developed economy has such a gap between the productivity of its capital city and its second and third cities, so we must drive up the performance of our regional cities”. Addressing productivity barriers and building major road and rail links are part of his solution.

Another ingredient is a research and development component of the NPIF plan. Here, £4.7bn over five years is intended to boost UK productivity by encouraging industry to work with the UK’s renowned science base. Innovate UK, the government’s innovation support agency, will take a primary role in managing these new forms of engagement to pull through new concepts into innovations and products – a transformation that so far has been unproductive in the UK.

Welcoming the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement, the chief executive of Innovate UK, Ruth McKernan said: “the Industrial Strategy Challenge fund will put business-led innovation at the heart of the industrial strategy. It will help deliver business growth for companies across the nations and regions, supporting the industries of tomorrow, boosting productivity in our existing areas of strength and help us realise commercial benefit from our world-class research base.

“We see this funding as a huge vote of confidence in the game-changing opportunity for businesses right across the UK to foster a culture of innovation, so that no matter where you are, or your level of skills, you can be supported to get your innovative idea off the ground to grow and scale your business.” Dr McKernan said.

Biopolis, Singapore

Philip Hammond received broad business and political approval for his considered approach in the Autumn Statement. Its success is likely to be a matter of scale and timescale. Singapore has a population of 5.4 million and occupies an area about half the size of London. Visitors can only be amazed at the scale of investment in its infrastructure and partners recognise the critical mass of technological talent that is drawn there from across the world. Biopolis, a district of Singapore dedicated to biotechnology, provides a vision of an innovation landscape.

Innovation takes time and patience and Mr Hammond in his discussions with colleagues may find both in short supply. The NPIF funding will not deliver its fruits within the expected Brexit timescale without some lengthy transition period to smooth the exit of the UK from the European Union.

His vision of a highly productive and open UK economy will need to include international trading partners, including Europe, as well as domestic markets and the UK will need to continue to have access to talent from overseas to be productive and competitive in global markets. It is a future UK economy with growth achieved more through productivity gained from innovative technology, replacing a labour supply that today has been increasing more in quantity than quality.

However, the problem of productivity that is afflicting the UK is not well understood, so the transition to Mr Hammond’s future could prove problematic. It appears that the problem could be due to a weakness of “total factor productivity”, which accounts for the efficiency with which input factors (labour, capital, and technology) are combined in production. Business schools refer to the capacity of industry to “absorb” innovation as a fundamental barrier to its uptake.

Recently, the UK’s Office of National Statistics (ONS) brought together leading academics and researchers to help solve this productivity puzzle in a new centre that will be based at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR).

The NIESR centre’s partners are currently beginning to coordinate and schedule their work which will lead to new research on best ways to measure emerging forms of economic activity in a globalised world. In February 2017 an international conference will bring together respected economists from around the world to help shape its – and possibly the UK’s – future direction and priorities.

By John Egan

(1) Data adjusted for ONS classification decisions that have been announced but not yet implemented

UK Innovation and Innovate UK

UK Innovation and Innovate UK

The UK has fallen to 3rd place (behind Switzerland and Sweden) in The Global Innovation Index 2016, an international league recognising effective innovation policies for development. Five years ago, the UK was in 10th place. Quality of innovation in the UK is recognised largely as a result of its world-class universities. Weaknesses in the UK were identified to be in general infrastructure, knowledge absorption, and intangible assets (such as brands, business models and culture).

The challenge for decades has been to better connect the knowledge generating universities of renowned excellence with the UK’s innovation exploiting business sector. Drivers on either side of the divide have not been well aligned.

Innovate UK is the government agency engaged in this challenge. With annual funding of about £560 million, Innovate UK provides match-funding support for innovative business. Support is also channelled through Catapult Centres that provide specialist resources in strategic business sectors. Knowledge Transfer Networks (KTN) and the Enterprise Europe Network provide knowledge gathering and dissemination functions to complete Innovate UK’s innovation tool box.

Legislation currently going through Parliament proposes that Innovate UK becomes integrated into UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) alongside its seven Research Council cousins that directly fund pure and applied research in UK universities and some of the functions of the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). This new co-existence of Government funding agencies should serve to better link the knowledge generation and innovation activities as anticipated in the 2016 Autumn Statement.

Chief-Exec.com earlier this month reported on the change in the portfolio of Innovate UK funding instruments from just grants to include various types of grants and loans and equity sharing as means to support innovation as it passes through the technology readiness pipeline.

Following the Autumn Statement, the UKRI and Innovate UK interests are set to expand as they take on three new activities:

- Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund (ISCF) – for funding cross-disciplinary collaborations between business and the UK science base. Identifiable challenges will be set for UK researchers to tackle. While the exact workings of the ISCF are yet to be confirmed, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) programme in the US is seen as a model that it may follow. The fund will cover a broad range of technologies, to be decided by an evidence-based process

- Innovation, applied science and research – additional funding awarded to researchers through the UKRI to increase research capacity and business innovation on the basis of national excellence. This will include a substantial increase in grant funding through Innovate UK

- Tech transfer and R&D facilities – Already the government has committed an additional £100m until 2020-21 to extend and enhance a Biomedical Catalyst programme. Additional funding of £100m over the same period will incentivise university collaboration in technology transfer and in working with business

In addition, the Autumn Statement points to two further forms of intervention in R&D to support its productivity objectives:

- R&D tax environment – the government will review the tax environment for R&D to look at ways to build on the introduction of the “above the line” R&D tax credit to make the UK a more competitive place to do R&D

- Science and Innovation Audits – A second wave of eight audits have been announced. These audits gather the evidence to identify places that can drive economic growth by focusing on their own research-driven sources of competitive advantage. The evidence then feeds into a “Smart Specialisation” strategy based on location in England and their equivalents in the Devolved Administrations. A call for expressions of interest to participate in a third round of Science and Innovation Audits has recently been announced