It is official

The economic weather following the Brexit referendum on June 23 was generally mild. Earlier stormy forecasts proved to be off the mark, though a few areas have witnessed significant disturbance.

A slew of new economic data has provided the first definitive evidence that confirms the observations of sentiment indicators that we have used in Chief-Exec.com to gain early and provisional insights into the economic response to the decision by the UK to leave the European Union (EU)

In its assessment of the post-referendum economy, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) concluded: “although the picture is still emerging, there has been no major collapse in confidence and within the data that is available there are indications of continued momentum in the economy”.

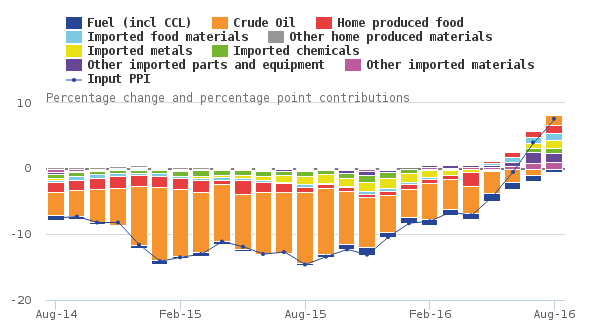

One cloud on the horizon is a consequence of the sharp drop in the value of sterling, which has increased producer input prices since July. The ONS report indicates that UK producers appear not to have passed all of their input price rises on to their customers. After two years with a negative Producer Price Index (PPI) – shown above – this inflation index has recently moved into positive territory with a value of 7.6 per cent in August. It should not be ignored. Pressures must exist on output prices with a likelihood of an increase in consumer price inflation.

This is not entirely a Brexit effect, but a significant fall in sterling will exacerbate the worsening conditions.

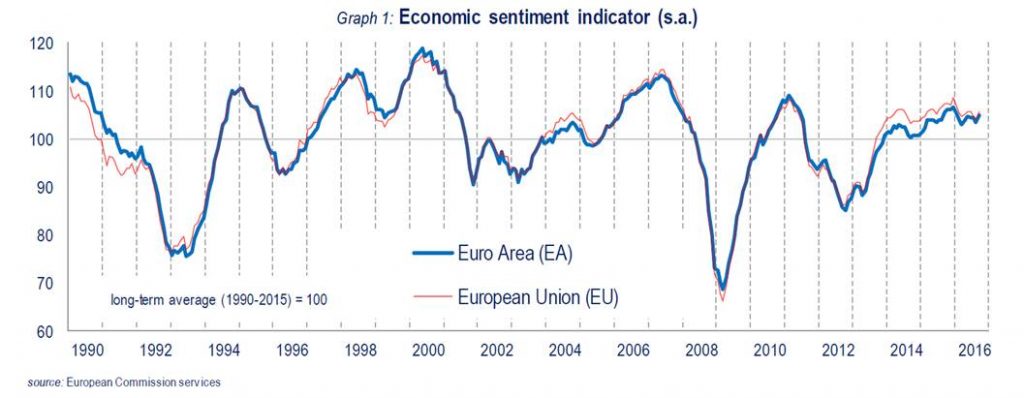

The sentiment indicators, meanwhile, continue to paint a picture of business as usual for the economies of both the UK and EU. Commentary on the European Sentiment Indicator (above) indicates that the September index improved in both the eurozone and the EU as a whole, following three months of negative or flat trends. Compared to recent history, the indicator is experiencing a relatively tranquil period. The same can be said for the closely watched Markit/CIPS PMI® indices for UK Manufacturing and UK Services, in which both sectors indicate a restoration of normal business activity after some significant drops immediately post-referendum.

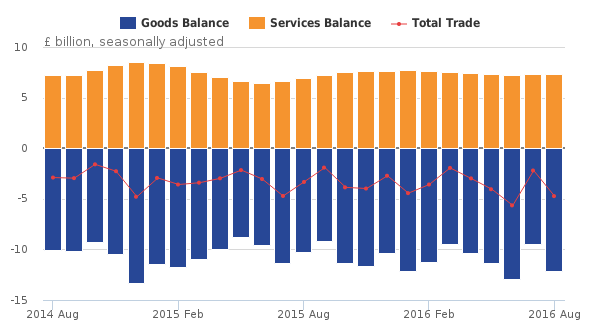

Credit: Office of National Statistics

Trade balances (Exports minus Imports) up to August, shown above, do not reveal any detectable Brexit effect. Services continue to provide a net positive contribution to the UK balance to partly offset a larger deficit due to trade in goods. In August the estimated overall trade deficit rose to £4.7bn from £2.5bn in July. This fluctuation lies within its normal range of recent monthly variation.

Two puzzles

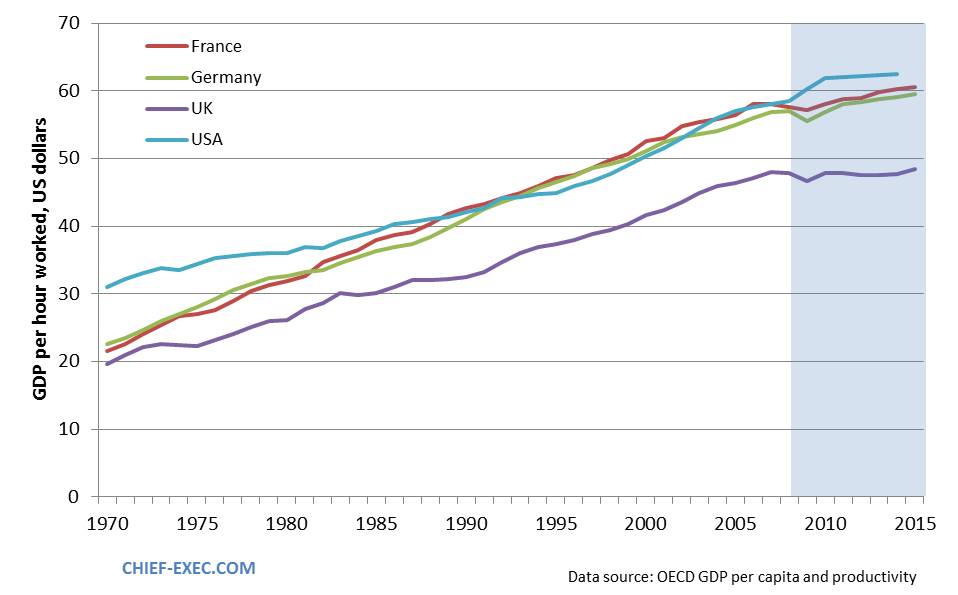

Something interesting and possibly worrisome has emerged from new work undertaken by the ONS on worker productivity in the UK. This has led to the identification of two “puzzles” that the ONS has sought to fathom out. Both puzzles are illustrated by the graph below, with data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The first “puzzle” is that the UK has seen barely any growth in worker productivity in the shaded area that marks the period following the onset of the economic downturn in 2008. Output (GDP) per hour worked had seen uninterrupted growth since the 1970s and had an average quarterly rate of about 0.5 per cent in the decade prior to 2008. This has slowed to just 0.1 per cent and output per hour is just now reaching its pre-recession level.

Since the 2008 recession, the recovery of UK productivity has been much weaker than in any of the economic recoveries of the past 50 years.

The ONS also has a second “puzzle” revolving round the UK’s long enduring “productivity gap” shown above with France, Germany and the USA. While a slowdown in productivity has been seen across advanced economies, the failure to return to growth in the UK has caused this productivity gap to widen in recent years.

The GDP per hour worked in France, Germany and in the USA in 2015 was about 25 per cent more than that of the UK worker.

Is there a systemic problem inhibiting the return to productivity growth in the UK? The weak productivity growth in recent years appears to be due to a weakness of “total factor productivity”, which accounts for the efficiency with which inputs (labour, capital, technology) are combined in production.

The ONS productivity report seeks to introduce new forms of analysis to unravel what is going on.

One approach being taken is to collect information on structured management practices among UK businesses, which have been shown to correlate with productivity. Structured management practices are seen to be more prevalent among larger businesses compared to the smaller businesses that account for a majority of UK manufacturing.

But doesn’t this rather gloomy picture conflict with what is widely broadcast, that the UK economy is generally sound and is out-performing its G7 partners with quarterly growth of 0.7% in June?

The Guardian has reported that consumer confidence has recovered to its pre-referendum level and it is this household spending that is the main driver of current economic growth.

On the production side, the ONS reports that the contribution of labour to recent growth is almost entirely related to a rise in the number of hours worked, through net inward migration together with higher employment rates. This effect dwarfs the minimal growth obtained by improving labour quality through education and on-the-job training.

The rise in employment rates in the UK – specifically for UK nationals – has also featured in a recent twitter discussion.

British workers already HAVE British jobs. The employment rate for UK nationals is the highest since at least ’97 (as far back as data goes) pic.twitter.com/ZFhzZaksIO

— Sarah O’Connor (@sarahoconnor_) October 5, 2016

This data prompted Financial Times editor Lionel Barber to re-tweet with the message,

“Killer graph for all those inclined to shut out those bloody foreigners stealing British jobs…..”

The average hours worked per worker in the UK are lower today than they were 20 years ago – in part because of the growth of part-time working. Individual decisions to limit the number of working hours, along with rising UK national employment and a likely fall in the economic contribution of overseas labour, will mix together to determine the labour supply to the future UK economy. A resuscitation of worker productivity will be important for its performance.

By John Egan

Chief-Exec.com

DataBox Article