A slew of new United Kingdom productivity statistics were yesterday released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The headlines tell a familiar story, but dig deeper and the UK appears a more mysterious place than the headlines suggest, writes John Egan.

The UK economy gives rise to a “productivity puzzle” that we have visited on several occasions at Chief-Exec.com.

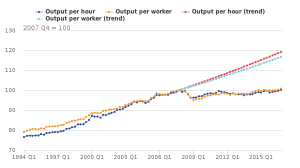

Since the financial crisis of 2007, the productivity of the UK worker has stalled. For the past decade the value he or she produces during each working hour has hardly changed.

This is quite unlike the rebound of worker productivity that was seen following previous financial downturns.

The absence of productivity growth has profound social and economic consequences. The inability to increase the gross value added (GVA) each hour by workers holds back the financial performance of their employer, the income available for their remuneration and the overall gross domestic product (GDP) of their country.

That the resilience of UK GDP is held up as a symbol of the prevailing strength of the country’s economy following Brexit may be reasonable. But, while this GDP growth is due to an increase in the quantity of labour (see top figure), the low productivity growth indicates a lack of quality of that labour in its ability to improve the standard of living of workers and the competitiveness of their companies.

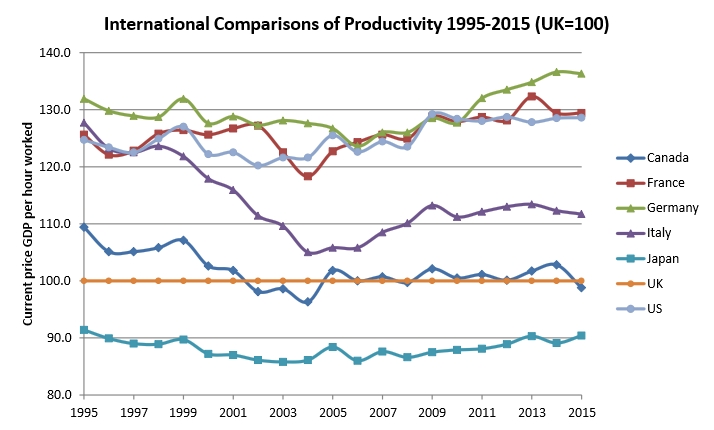

Furthermore, there is a longstanding gap between what the UK worker can produce in a day and that for workers of other G7 economies. Currently, this gap stands at a staggering 16 per cent.

Like its record in international football, this is a familiar story of national mediocracy that has prevailed since the 1960s. However, the finer detail that is reported in the latest data from the Office for National Statistics shows more of a patchwork quilt of economic performance through the industrial sectors and geographical regions that make up the UK economy.

Credit: ONS

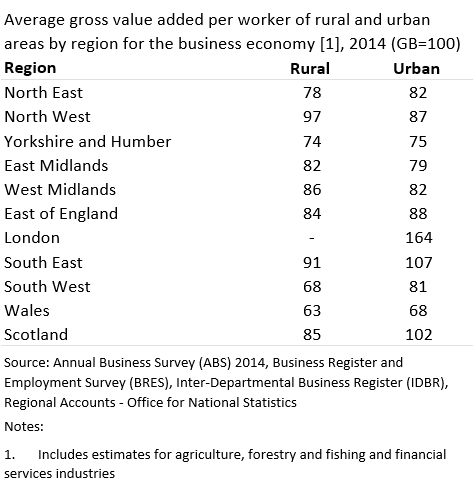

All regions are not the same

The relative economic performance of regions and their urban or rural areas varies across the country. In Scotland, London and the south of England, urban areas are more productive than their rural neighbours. The productivity gap between these rural and urban areas is about 17 percentage points.

This effect is consistent with an economic theory that suggests companies in urban areas should have greater productivity due to the proximity of supply chains, knowledge environment, specialised labour and network effects.

However, on the contrary, the productivity gap between rural and urban areas is small in the Midlands and north of England. Indeed, in the North West, rural areas outperformed urban areas. Understanding these regional differences may be important in finding ways to improve regional productivity.

All sectors are not the same

Contributions to growth of whole UK economy output per hour. Seasonally adjusted, cumulative 2008-2016. Credit: ONS

Non-financial services, followed by manufacturing and construction, made positive contributions to UK productivity growth between 2008 and 2016. These are partly offset by negative contributions from non-manufacturing production such as agriculture, mining, utilities and finance. An allocation effect is used to account for a flow of labour between sectors and the negative value here indicates a movement from higher to lower productivity industries in recent years.

All companies are not the same

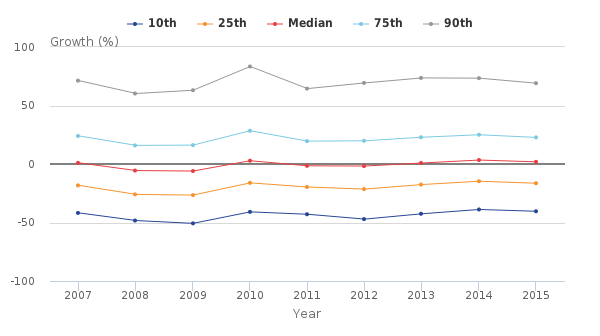

Growth of real gross value added per worker by percentile. Credit: ONS

It is no surprise that companies perform differently in terms of their productivity. Those at the frontier of technology and management that occupy the tenth percentile in their productivity performance show well over 50 per cent growth of GVA. However, the gap between these frontier companies and the average and worst performers shows no sign of narrowing. Hence, the aggregated behaviour across the UK is the flat-lining of GVA for a decade.

The weakness of productivity growth, to varying degrees, is a global phenomenon. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has responded with a Future of Productivity report in which they place emphasis on the need for the frontier companies to lead the laggards into a more productive world. Policies to recharge productivity across the globe are proposed – including those providing a skilled workforce, as well as those leading to the demise of so-called “zombie” companies that otherwise would trap their employees in an unproductive future.

Success in implementing the policies that lead to a more productive future could also bring a social and political dividend.

French economist Thomas Piketty in a recent blog observes, “… the persistent backwardness in British productivity, which never reached the American level, is usually attributed to the historical weaknesses in the educational system”.

If productivity can provide a basis for international economic relations, as Piketty proposes, it should be possible to develop policies for the benefit of national populations.

Follow on twitter: @johnmegan