John Egan reporting from Paris.

Once again it seems that the status quo is a poisoned recipe in politics.

Another election has seen a candidate with policies that not so long ago would have been considered fantastical, winning by a considerable margin.

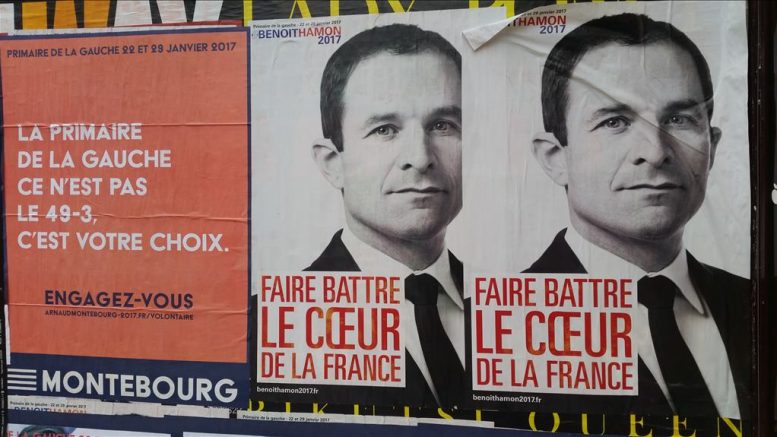

This time, a coalition of some French left wing parties (La Belle Alliance Populaire), which includes the Socialist Party (PS) that currently holds power, has elected Benoît Hamon to run in the forthcoming presidential election in May. In doing so it has distanced itself from most of the policies of the incumbent president François Hollande and recent prime minister Manuel Valls. Valls, who was representing the traditional social democratic centre-left, was beaten tonight by Hamon in the second round of the presidential primary by 58.5 per cent to 41.5 per cent.

The surprising rise of Benoît Hamon has been due to his convincing articulation of a series of radical policies. The most famous of which was his ‘revenu universel’ which aims to give €750 a month to every French citizen, whether in work or not, as a basic living wage upon which the income from work can be added.

The ‘revenu universel’ has been estimated to cost the French treasury €450 billion. Realising the infeasibility of this measure, Hamon has retreated to proposing an initial test of the idea at a cost of €40bn to be financed by raising taxes on property, land and the wealth of the most prosperous.

In the end, as the nature of work changes with new technology, for example, so should the nature of income change, with a ‘revenu universel’ paid for by a tax on the robots that replace human workers.

More broadly Benoît Hamon proposes an end to a prolonged period of austerity throughout which the French budget deficit obstinately resisted all measures to reduce this to the 3 per cent of GDP level demanded for members of the European Union. Hamon prefers a Keynesian solution to allow public spending to exceed 7 per cent of GDP.

While these economic ideas might raise eyebrows in Brussels and Berlin, as with all mainstream political parties in France, including the Front National of Marine Le Pen, the desire is to remain in the European Union. Indeed, Hamon proposes a mutualisation and re-financing of European debt by the European Central Bank (ECB) and would like to return to a socialism that is European in its relationships and outlook.

A significant part of Benoît Hamon’s winning formula is the tight association of his socialist policies and principles with outcomes that are environmentally sustainable. Indeed, he has said it is now difficult to consider one a socialist without also being an ecologist. Multinational agro-chemical businesses and the use of pesticides and endocrine disrupting chemicals, centralised and non-sustainable energy sources, and even the capitalist system itself with its demand for economic growth at any cost are targets for Hamon’s ire.

Add to this tolerance for the recreational use of cannabis, for pragmatic reasons – its criminalisation just doesn’t work – and the welcome support for migrants in distress, for humanitarian reasons. France, he believes, could do a lot more to accommodate refugees seeking asylum.

All the above are articulated in a coherent and convincing manner to suggest there is an alternative to the dominant neoclassical economic capitalist system that is falling into disrepute across the world. This is what has appealed to the majority casting their vote in the socialist primary election, and what has led to the adoption of Benoît Hamon as their presidential candidate.

However, the best news in all of this seems to be for the increasingly popular Emmanuel Macron – the ex-banker and recent economy minister who is an independent presidential candidate with another bundle of radical policies to fix the competitiveness of the French economy. A Manuel Valls victory would have squeezed Macron’s natural constituency in the centre-left. As it is, Benoît Hamon is doing the same to another highly charismatic presidential candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon representing the Left Front.

According to French opinion polls, whoever won the socialist primary would end up in fifth place with about 12 per cent of the vote in the first round of the French presidential election in May. They would not then qualify for the two person second round run-off. However, the polls are not to be relied upon. And with presidential favourite François Fillon struggling to cast off historic Penelope-gate allegations of fraudulent payments to his wife, the race is wide open.

Could it be Macron, Le Pen or Fillon or could it be Mélenchon or Hamon?

Expect the unexpected.