Political leaders failed dismally to recognise that radical political and economic changes were making their constituents increasingly uneasy, Geoff Kitney writes.

When Donald Trump delivered his landmark, first speech to the United States Congress last week, it appeared to be greeted around the world with an almost audible sigh of relief.

An unmistakable change of tone from divisive and apocalyptic to optimistic and consensual was widely received as a sign that the president’s bumpy first five weeks in office had convinced Trump that the harsh tone he set in his inauguration speech needed to be changed to something more acceptable to middle America.

Trump had reached back towards the “sensible centre” of American politics, some critics suggested.

That he might have decided that the “sensible centre” was the better place to position his presidency after the disruptive impact of the snowstorm of harsh executive orders of his first weeks in the presidency was more a wish than a fact. The speech’s softer rhetoric had little of policy substance on which anyone could reasonably conclude that Trump had decided to reset his agenda to a more broadly acceptable set of policies.

“Judge him by deeds, not words,” cynics warned.

But the readiness to read hope into Trump’s words reflects a widely held concern, in the democratic West at least, that the tilt to the populist far right of the political spectrum which delivered the Brexit vote and the Trump presidency had set the world on a dangerous new path.

This has given rise to an increasingly urgent wish for political leaders to restore solidity to the political middle ground.

This is especially so in Europe where there is a palpable fear that the upcoming elections in France, the Netherlands, Germany and Italy could result in victories – or at best major gains – for the insurgent right-wing populists which could plunge the European Union (EU) into a deep existential crisis.

Ordinary people have become increasingly disillusioned with the “sensible centre”. If they have not already left it, they are finding fewer reasons to stay.

Victory for moderate politics in these elections is seen as the most important contribution Europe can make to restore a sensible balance to world affairs.

It is time, centrists argue, for a global shift back towards “the sensible centre”.

Their analysis of the problem is hard to refute.

Politics almost everywhere has experienced a rapid polarisation in the period since the 2007 global financial crisis.

The evidence can be found instantly on social media, especially on Twitter which has become the main platform for political “dialogue”.

Actually, dialogue is the wrong word. Volcanic eruption of extreme partisanship, nastiness and abuse would be a better description. In the Twittersphere, there is little middle ground.

The dominant users of Twitter are people of forceful and, often, extreme opinions. For many people it is a means to reinforce their own views and seek comfort in communication with like-minded people. Others simply use it as a megaphone.

The speed with which social media has taken over from the “old” media as the main medium of political expression has seen “sensible, moderate, reasoned, fact-based” political conversation evaporate.

But does this mean that ordinary people, the so-called “silent majority” have also deserted the “sensible centre”?

It is certainty the case that there is now deep confusion and unease among the ordinary voting populations in Western democracies. With the old reference points (the traditional media) shrinking and the Twitter-centered political conversation becoming so strident, it has become much more difficult for voters to find their way through the political landscape.

With so many angry and loud voices accusing and abusing the so-called “political elites”, finding reasoned and balanced information about the affairs of nations has become challenging and, in many cases, impossible.

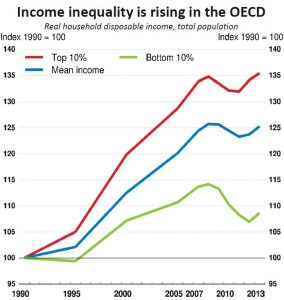

Disposable incomes have grown more in rich households, while the poorest families have become relatively poorer across OECD countries since 1990. Source: OECD.

There is also, however, no doubt that ordinary people have become increasingly disillusioned with the “sensible centre”. If they have not already left it, they are finding fewer reasons to stay.

The evidence is overwhelming that the process of economic reform for which political leaders and their advisers persuaded the “sensible centre” to embrace as a vital national interest has resulted in many ordinary people feeling betrayed.

The shift in wealth from ordinary wage and salary earners to the corporate elites, that has been a product of the market-reforms of the past two decades, has resulted in a widespread sense of unfairness and betrayal.

Immigration, which was one of the by-products of the increasing globalisation that has resulted from reforms that have removed barriers to trade, has turned into a lightning rod of discontent among the ordinary populations.

In Europe, where the evolution of the EU was profoundly changing the relationships between ordinary people and those who govern them, the arrogant assumption that ordinary people would come to accept the reality of a borderless, single market with shared sovereignty has created fertile ground for populists selling nostalgic, nationalistic visions.

Political leaders have failed dismally to recognise that these changes were making their constituents increasingly uneasy and less willing to accept them.

The loss of trust with the political establishment that this has led to is now obvious and dangerous.

With populists prominent everywhere you look, leaders capable of restoring confidence in the “sensible centre” are hard to find. Former British prime ministers Tony Blair and John Major have raised powerful questions about Brexit which, it could be argued, represent “sensible centre” views capable of drawing people back. But they are not the leaders for this task.

Maybe French presidential hopeful Emmanuel Macron is the best hope for the beginning of a fight back for centrist ideas and policies. It certainly seems that much hope is being invested in him. So much so that if he fails in France in two months time, the hopes of those who believe in the future of the EU and in a progressive centrist future as the best future available will turn to despair.