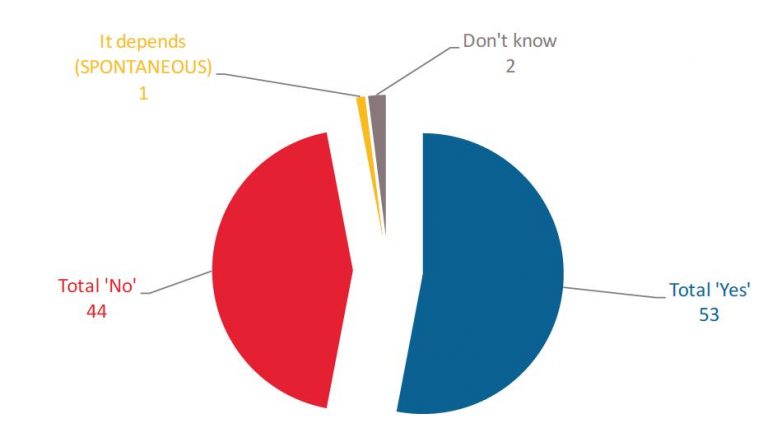

Almost one in two European citizens do not believe their national media provide trustworthy information and more than half think they are not free from political or commercial pressure, a European Union survey has found.

More than half of respondents believed social media was not a reliable source of information, and among active social media users, three out of four people had heard, read, seen or experienced cases of abuse, the report Media pluralism and democracy said.

Frans Timmermans, first vice-president of the European Commission, said late last week that the freedom to receive and impart information and the pluralism of the media were enshrined in the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights.

“We have very good reasons for that: freedom of the media is the backbone of the values on which this Union is built. A free and pluralist media is the watchdog in our democracy.”

The survey, published last Thursday, was conducted by Eurobarometer on behalf of the European Commission. Almost 28,000 citizens from all social categories across the EU’s 28 member states participated.

Aidan White, director and chief executive of the Ethical Journalism Network, said greater investment and more resources are needed to ensure quality journalism to allow the media to function as society’s “watchdog”. Read the full story below

Mr Timmermans, a former Dutch foreign affairs minister, said the issue of media pluralism and democracy, in a “post-truth” world – a term recently enshrined in the Oxford English Dictionary – “has become even more topical given global developments and given some of the elections and referendum campaigns that we have seen, where the use of information and disinformation played a huge role”.

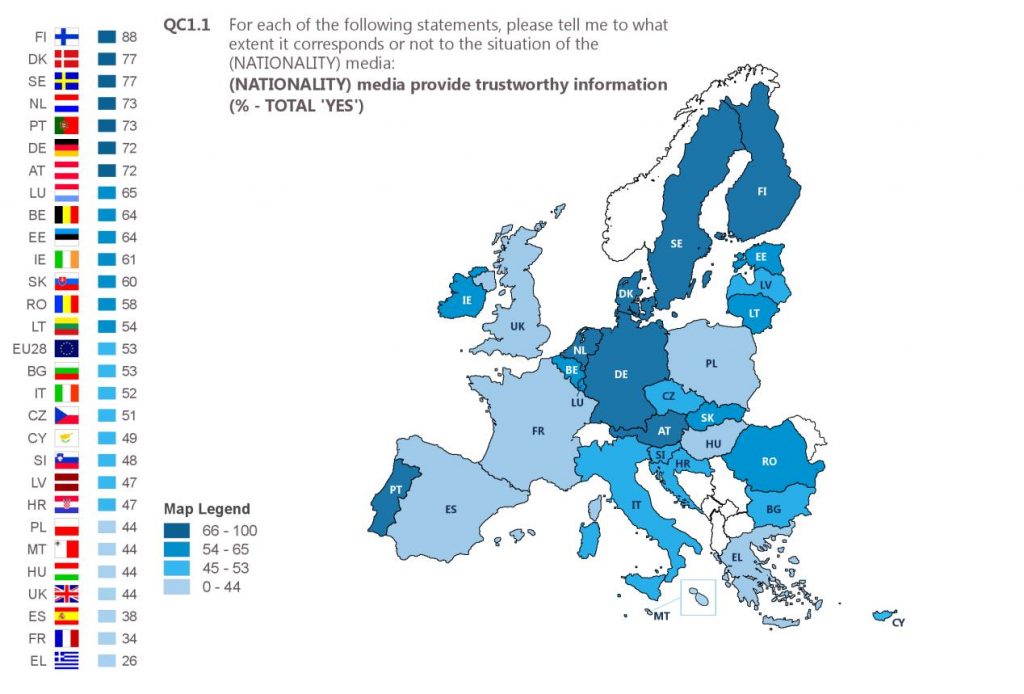

The survey found that low levels of trust in traditional media were more acute in southern countries such as Greece (26 per cent), France (34 per cent) and Spain (38 per cent) – with the exception of Portugal (73 per cent) – especially among the least well off and least educated.

However, in Scandinavian countries a much higher proportion of citizens trusted their national media – with Finland at 88 per cent, Sweden and Denmark at 77 per cent, and other northern countries such as The Netherlands at 73 per cent, and Germany and Austria at 72 per cent.

In Ireland, 61 per cent of respondents believed their media provided trustworthy information, but only 44 per cent of citizens in the United Kingdom had faith in their media outlets.

The survey was conducted between September and October, after the UK Brexit vote, but before the election of US President-elect Donald Trump.

Traditional journalism is in decline. The media has been accused of bias – against Brexit and Trump – and mocked for getting both votes wrong.

Meanwhile, the use of social and other online media, including “fake news websites”, is on the rise, especially among the young.

Günther Oettinger, EU Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society, stressed: “quality and fact-based journalism are essential to our democracies”.

The survey results echo a trend already observed in the US where, according to a survey by Gallup this month, “a majority of registered voters (52 per cent) say election media bias favours Clinton”, while an earlier poll in September revealed that Americans’ trust and confidence in the mass media “to report the news fully, accurately and fairly” had dropped to its lowest level at 32 per cent.

Credit: European Commission

European citizens not only showed low levels of trust in their national media, but also raised concerns about the rise of hate speech online, the Eurobarometer report found.

Although a majority of respondents (55 per cent) think social media is not a reliable source of information – the figure is much higher in Sweden (80 per cent), the Netherlands (73 per cent) and Finland (68 per cent) – 53 per cent said they follow debates on social media. “For example, by reading articles on the Internet or through online social networks or blogs.”

Among those active on social media, a large majority (75 per cent) had “heard, read, seen or themselves experienced cases where abuse, hate speech or threats are directed at journalists/bloggers/people”. As a result, almost half of them (48 per cent) said that they are discouraged from engaging in online debates.

Věra Jourová, Commissioner for Justice, Consumers and Gender Equality, said: “citizens need to feel safe expressing themselves in the online environment and journalists must be able to go about their work free of interference”.

The second Annual Colloquium on Fundamental Rights, where EU officials, NGOs, journalists, media representatives, companies and academics gathered to discuss the topic of Media Pluralism and Democracy, was led by Mr Timmermans, Mr Oettinger, and Ms Jourová, at the European Commission in Brussels.

Its conclusions, on “the key role in democratic societies of a free and pluralist media, and in particular digital media”, are to be published this week.

The report concluded that “in the eyes of Europeans, there is still considerable work to be done in ensuring the independence of national media”.

By Katia Yezli

Point of View

Greater investment and more resources are needed to ensure quality journalism to allow the media to function as society’s “watchdog”.

That is the view of Aidan White, director and chief executive of the Ethical Journalism Network (EJN), one of the panellists at the European Commission’s recent Colloquium on Fundamental Rights on Media Pluralism and Democracy.

This is an edited version of Mr White’s Q&A with Chief-Exec.com yesterday:

● The media appear to have failed to connect with that part of their audience that is frustrated, even angry, at the failure of political leaders to address the social and economic crisis. As the media have not given a voice to these people, who believe they have been ignored and forgotten, they are increasingly seen, as a result, as part of the problem, not the solution. And one major reason why the media have failed to connect with these alienated communities is that they no longer have the resources to spend on research and reporting [in the field].

● Journalism is also losing the capacity to fulfil its public purpose because of changing habits in the way people receive and disseminate information. The social networks and Internet services work against the traditional notion of pluralism. The creation of filter bubbles in which people only expose themselves to like-minded people who largely agree with their own world view is leading to greater polarisation in society. Journalism should be about providing all sides of a story, to help people understand complex issues and to help them make up their minds. But what if people are just not interested in other points of view?

● First of all, we need greater recognition within the governing and political class that democracy is at risk as these trends intensify. We also need to invest more to support independent and ethical journalism and provide urgently needed resources to allow journalism to function as a watchdog of society. We need to rethink the public service value of journalism and provide resources so that all voices can be heard, even those that don’t attract advertising, and the ones with uncomfortable messages for political elites.

● We need a new movement for media literacy that helps all of us understand better how to communicate responsibly, how to listen to others, and how to avoid abusive behaviour. Politicians or people in public life who tell malicious lies or exploit fake news, or who prefer propaganda, … need as much help in navigating the Internet and tips on using the tools of our age as do children or vulnerable groups.

● My key conclusion is that we should not look for scapegoats. Blaming technology or the failures of Facebook, Google and Twitter for the Brexit result or the Trump election is easy, but wrong. We need to invest in quality information, support programmes of public education in critical thinking, build new movements for debate and dialogue across society …, and show zero tolerance to racism and hate (including within the media).