One reason that Capital in the 21st Century has become a best seller is that it deals with issues of real significance for “baby boomers” and a generation on either side. Thomas Piketty enables this large audience to understand not only their place in society today but also in its economic history. He explains why some people thrive and some do not, and how winning is as much to do with good fortune as it is a sign of merit.

Our first bite into Capital in the 21st Century covered the consequences of an unprecedented destruction of capital in the 50 years after 1915. This had the effect of resetting the financial destiny of those alive at that time – the baby boomers and their parents.

Our first bite into Capital in the 21st Century covered the consequences of an unprecedented destruction of capital in the 50 years after 1915. This had the effect of resetting the financial destiny of those alive at that time – the baby boomers and their parents.

The older generation did not have enough lifetime left to restore lost assets through work which had become, briefly, as significant as owning capital to being rich. They died poorer than history may have led them to expect. The baby boomers, on the other hand, had plenty of time to amass fortunes through work and in value of capital assets in a rapidly growing post-war economy.

In the second part of our series we followed these changes to the current day with a partial restoration of the wealth of capital owners towards levels that existed for centuries before the calamitous wars and recessions of the 1900s. There was one important difference though.

In the second part of our series we followed these changes to the current day with a partial restoration of the wealth of capital owners towards levels that existed for centuries before the calamitous wars and recessions of the 1900s. There was one important difference though.

Rather than a high concentration of wealth in an elite group of the very wealthy – the 1 and 10 per cent fractions – the 50 to 89 per cent of the wealthy baby boomers had grabbed a share. This large demographic bolus of a reasonably rich “patrimonial middle class” became a novel feature in contemporary society.

Today the patrimonial middle class have moved up a generation. They are enjoying the benefits of longevity with an expectation of a long retirement funded by the fruits of their labour and investments. Their property assets have done particularly well. Many have had children who are now adults, and they are thinking of ways to pass on what they own.

These are the subjects of our third bite into Capital in the 21st Century.

The data that follows is drawn from the national accounts of France. They provide the most complete historical picture. Data from the UK and Germany is similar, indicating that patterns of wealth accumulation and inheritance behaviour are broadly comparable across Europe.

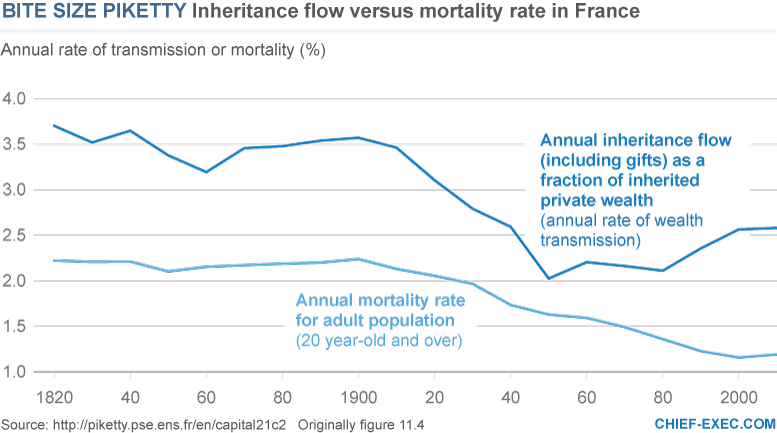

The above graph shows the mortality rate – the fraction of adults who will die in a given year. A striking feature is how this has fallen over the past 100 years to a value of 1.2 per cent. Life expectancy has increased from about 60 years in 1900 to 80 years today.

The annual rate of wealth transmission shown above is higher than the mortality rate because the average wealth of people who die is higher than that of the living. Throughout the 19th century people died owning about 1.6 times the average wealth of the living, when gifts given before death are taken into account. By 2010 the deceased were 2.2 times wealthier than their living counterparts.

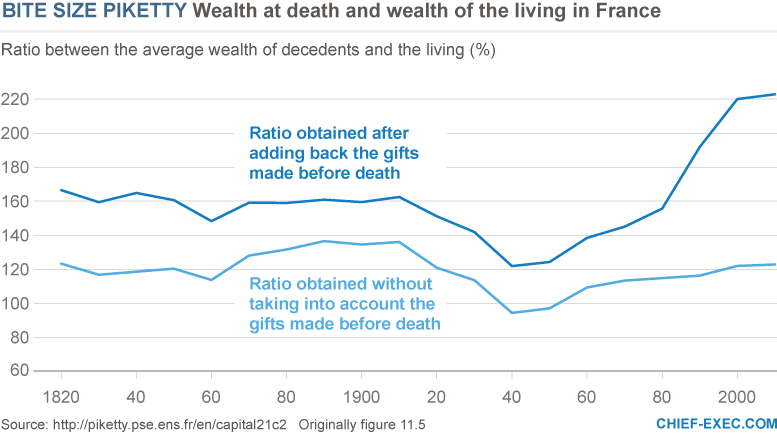

This ratio of wealth of the deceased to that of the living is shown below. Here, the higher line is when gifts given prior to death are accounted for in the wealth of the deceased. The lower line presents the same wealth ratio when gifts are not included.

It is notable that for a very brief period between 1940 to 1950 – and unique in recorded history – the living were slightly wealthier than the recently deceased, when gifts were not taken into account. This was followed by an impressive rise in the wealth of the dead relative to the living – when gifts are included – to hitherto unseen levels.

This pattern is due to the longevity of the baby boomers. Their average lifespan of 78 years gives time for their capital assets to grow, but it also has consequences for the generations that follow. A generational gap of 30 years between parents and their children has stayed constant for centuries – so that inheritors in 1900 would typically have received their inheritance at about 30 years of age. In 2010, whilst the amount is greater, it is received later in life, typically round the age of 50 years.

After 1980 a greater portion of inheritance is passed on before death in the form of gifts.

It is now normal for the wealthy, including the patrimonial middle class, to pass on some of their wealth to off-spring early. Perhaps it is a leg-up onto the property ladder, perhaps a first car, perhaps funding voyages of discovery or maybe even writing off a student debt. Later in life there may be more significant gifts as the comfort and care of younger generations supplants the care the old have for themselves.

It must be remembered that inheritance is only available from those who die leaving something of value behind. Many people die with little or no wealth at all.

According to Piketty, half of the population with the lowest incomes live on something close to the minimum wage, which in France amounts to €15,000 a year, and makes up €750,000 through the course of a 50-year adult lifetime including retirement. Since most of this money is needed to live, there is little if anything left to pass onto the next generation.

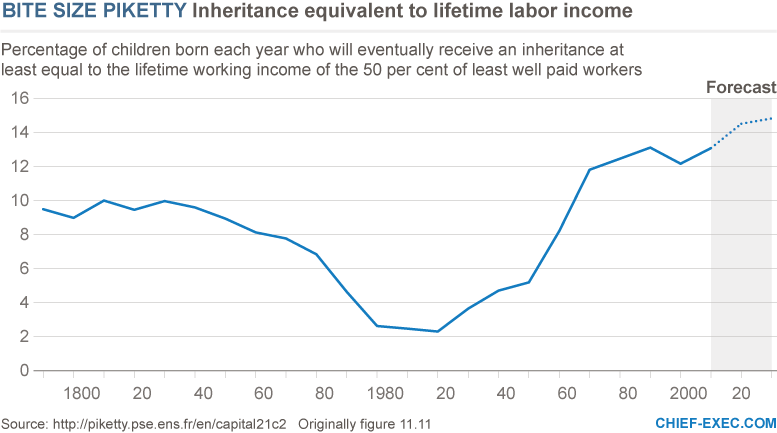

The graph below reveals that 13 per cent of children born between 1970-1980 will eventually receive in inheritance an amount at least equal to this lifetime working income of the bottom 50 per cent of less well paid workers.

This wider sharing out of inherited wealth is another consequence of the increased wealth held by the 50-89 per cent wealthiest patrimonial middle class. When wealth was at its most concentrated, around 1910, there were only about 2 per cent of those born who could expect to receive an inheritance greater than the lifetime earning of the poorest half of the population. Indeed, at the turn of the 20th century, the 50-89 per cent themselves were not much better off.

Piketty sees the latest trend as a “fairly disturbing form of inequality …. because it is a commonplace inequality opposing broad segments of the population rather than pitting a small elite against the rest of society”. It is a trend that challenges accepted notions of meritocracy. Also, as the wealthy cannot live forever, inheritance, just as in times past, provides the mechanism for capital to become increasingly concentrated and restore its domination over labour.

It seems that the good intentions of the reasonably well off in contemporary society, to look after their children, may have some insidious consequences for the society they will inherit.

By John Egan